On the consolations of philosophy

In 2002, Unesco declared the third Thursday of every November as World Philosophy Day, to celebrate "the enduring value of philosophy for the development of human thought, for each culture and for each individual". In celebrating the day, which falls on November 15 this year, In Focus publishes some excerpts from Alain de Botton's The Consolations of Philosophy, published in 2000, which examines everyday problems of our lives, and through the teachings of philosophers ranging from Socrates to Nietzsche, offers insight and understanding to the reader.

Every society has notions of what one should believe and how one should behave in order to avoid suspicion and unpopularity. Some of these societal conventions are given explicit formulation in a legal code, others are more intuitively held in a vast body of ethical and practical judgements described as "common sense", which dictates what we should wear, which financial values we should adopt, whom we should esteem, which etiquette we should follow and what domestic life we should lead. To start questioning these conventions would seem bizarre, even aggressive. If common sense is cordoned off from questions, it is because its judgements are deemed plainly too sensible to be the targets of scrutiny. It would scarcely be acceptable, for example, to ask in the course of an ordinary conversation what our society holds to be the purpose of work.

Ancient Greeks had as many common-sense conventions and would have held on to them as tenaciously. One weekend, while browsing in a second-hand bookshop in Bloomsbury, I came upon a series of history books originally intended for children, containing a host of photographs and handsome illustrations. The series included See Inside an Egyptian Town, See Inside a Castle and a volume I acquired along with an encyclopaedia of poisonous plants, See Inside an Ancient Greek Town.

There was information on how it had been considered normal to dress in the city states of Greece in the fifth century BC.

The book explained that the Greeks had believed in many gods, gods of love, hunting and war, gods with power over the harvest, fire and sea. Before embarking on any venture they had prayed to them either in a temple or in a small shrine at home, and sacrificed animals in their honour. It had been expensive: Athena cost a cow; Artemis and Aphrodite a goat; Asclepius a hen or cock.

The Greeks had felt sanguine about owning slaves. In the fifth century BC, in Athens alone, there were, at any one time, 80–100,000 slaves, one slave to every three of the free population.

The Greeks had been highly militaristic, too, worshipping courage on the battlefield. To be considered an adequate male, one had to know how to scythe the heads of adversaries. The Athenian soldier ending the career of a Persian (painted on a plate at the time of the Second Persian War) indicated the appropriate behaviour.

Women had been entirely under the thumb of their husbands and fathers. They had taken no part in politics or public life, and had been unable either to inherit property or to own money. They had normally married at thirteen, their husbands chosen for them by their fathers irrespective of emotional compatibility.

None of which would have seemed remarkable to the contemporaries of Socrates. They would have been confounded and angered to be asked exactly why they sacrificed cocks to Asclepius or why men needed to kill to be virtuous. It would have appeared as obtuse as wondering why spring followed winter or why ice was cold.

But it is not only the hostility of others that may prevent us from questioning the status quo. Our will to doubt can be just as powerfully sapped by an internal sense that societal conventions must have a sound basis, even if we are not sure exactly what this may be, because they have been adhered to by a great many people for a long time. It seems implausible that our society could be gravely mistaken in its beliefs and at the same time that we would be alone in noticing the fact. We stifle our doubts and follow the flock because we cannot conceive of ourselves as pioneers of hitherto unknown, difficult truths.

It is for help in overcoming our meekness that we may turn to the philosopher.

***

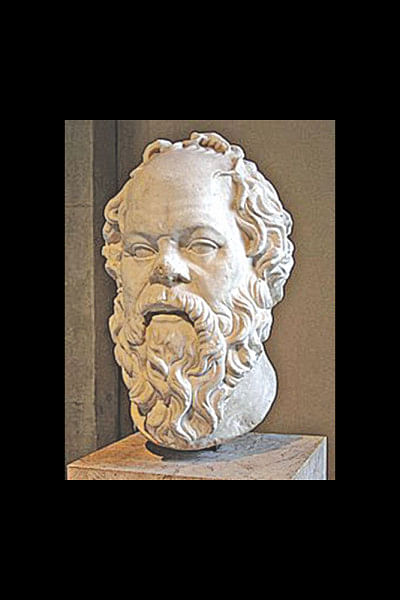

He was born in Athens in 469 BC, his father Sophroniscus was believed to have been a sculptor, his mother Phaenarete a midwife. In his youth, Socrates was a pupil of the philosopher Archelaus, and thereafter practised philosophy without ever writing any of it down. He did not charge for his lessons and so slid into poverty; though he had little concern for material possessions. He wore the same cloak throughout the year and almost always walked barefoot (it was said he had been born to spite shoemakers). By the time of his death he was married and the father of three sons. His wife, Xanthippe, was of notoriously foul temper (when asked why he had married her, he replied that horsetrainers needed to practise on the most spirited animals). He spent much time out of the house, conversing with friends in the public places of Athens. They appreciated his wisdom and sense of humour. Few can have appreciated his looks. He was short, bearded and bald, with a curious rolling gait, and a face variously likened by acquaintances to the head of a crab, a satyr or a grotesque. His nose was fat, his lips large, and his prominent swollen eyes sat beneath a pair of unruly brows.

But his most curious feature was a habit of approaching Athenians of every class, age and occupation and bluntly asking them, without worrying whether they would think him eccentric or infuriating, to explain with precision why they held certain common-sense beliefs and what they took to be the meaning of life—as one surprised general reported:

Whenever anyone comes face to face with Socrates and has a conversation with him, what invariably happens is that, although he may have started on a completely different subject first, Socrates will keep heading him of as they're talking until he has him trapped into giving an account of his present life-style and the way he has spent his life in the past. And once he has him trapped, Socrates won't let him go before he has well and truly cross-examined him from every angle.

He was helped in his habit by climate and urban planning. Athens was warm for half the year, which increased opportunities for conversing without formal introduction with people outdoors. Activities which in northern lands unfolded behind the mud walls of sombre, smoke-filled huts needed no shelter from the benevolent Attic skies. It was common to linger in the agora, under the colonnades of the Painted Stoa or the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios, and talk to strangers in the late afternoon, the privileged hours between the practicalities of high noon and the anxieties of night.

The size of the city ensured conviviality. Around 240,000 people lived within Athens and its port. No more than an hour was needed to walk from one end of the city to the other, from Piraeus to Aigeus gate. Inhabitants could feel connected like pupils at a school or guests at a wedding. It wasn't only fanatics and drunkards who began conversations with strangers in public.

If we refrain from questioning the status quo, it is—aside from the weather and the size of our cities—primarily because we associate what is popular with what is right. The sandalless philosopher raised a plethora of questions to determine whether what was popular happened to make any sense.

***

One afternoon in Athens, to follow Plato's Laches, the philosopher came upon two esteemed generals, Nicias and Laches. The generals had fought the Spartan armies in the battles of the Peloponnesian War, and had earned the respect of the city's elders and the admiration of the young. Both were to die as soldiers: Laches in the battle of Mantinea in 418 BC, Nicias in the ill-fated expedition to Sicily in 413 BC. No portrait of them survives, though one imagines that in battle they might have resembled two horsemen on a section of the Parthenon frieze.

The generals were attached to one common-sense idea. They believed that in order to be courageous, a person had to belong to an army, advance in battle and kill adversaries. But on encountering them under open skies, Socrates felt inclined to ask a few more questions:

SOCRATES: Let's try to say what courage is, Laches.

LACHES: My word, Socrates, that's not difficult! If a man is prepared to stand in the ranks, face up to the enemy and not run away, you can be sure that he's courageous.

But Socrates remembered that at the battle of Plataea in 479 BC, a Greek force under the Spartan regent Pausanias had initially retreated, then courageously defeated the Persian army under Mardonius:

SOCRATES: At the battle of Plataea, so the story goes, the Spartans came up against [the Persians], but weren't willing to stand and fight, and fell back. The Persians broke ranks in pursuit; but then the Spartans wheeled round fighting like cavalry and hence won that part of the battle.

Forced to think again, Laches came forward with a second common-sense idea: that courage was a kind of endurance. But endurance could, Socrates pointed out, be directed towards rash ends. To distinguish true courage from delirium, another element would be required. Laches' companion Nicias, guided by Socrates, proposed that courage would have to involve knowledge, an awareness of good and evil, and could not always be limited to warfare.

In only a brief outdoor conversation, great inadequacies had been discovered in the standard definition of a much-admired Athenian virtue. It had been shown not to take into account the possibility of courage off the battlefield or the importance of knowledge being combined with endurance. The issue might have seemed trifling but its implications were immense. If a general had previously been taught that ordering his army to retreat was cowardly, even when it seemed the only sensible manoeuvre, then the redefinition broadened his options and emboldened him against criticism.

In Plato's Meno, Socrates was again in conversation with someone supremely confident of the truth of a common-sense idea. Meno was an imperious aristocrat who was visiting Attica from his native Thessaly and had an idea about the relation of money to virtue. In order to be virtuous, he explained to Socrates, one had to be very rich, and poverty was invariably a personal failing rather than an accident.

We lack a portrait of Meno, too, though on looking through a Greek men's magazine in the lobby of an Athenian hotel, I imagined that he might have borne a resemblance to a man drinking champagne in an illuminated swimming pool.

The virtuous man, Meno confidently informed Socrates, was someone of great wealth who could afford good things. Socrates asked a few more questions:

SOCRATES: By good do you mean such things as health and wealth?

MENO: I include the acquisition of both gold and silver, and of high and honourable office in the state.

SOCRATES: Are these the only kind of good things you recognise?

MENO: Yes, I mean everything of that sort.

SOCRATES: … Do you add 'just and righteous' to the word 'acquisition', or doesn't it make any difference to you? Do you call it virtue all the same even if they are unjustly acquired?

MENO: Certainly not.

SOCRATES: So it seems that justice or temperance or piety, or some other part of virtue must attach to the acquisition [of gold and silver] … In fact, lack of gold and silver, if it results from a failure to acquire them … in circumstances which would have made their acquisition unjust, is itself virtue.

MENO: It looks like it.

SOCRATES: Then to have such goods is no more virtue than to lack them …

MENO: Your conclusion seems inescapable.

In a few moments, Meno had been shown that money and influence were not in themselves necessary and sufficient features of virtue. Rich people could be admirable, but this depended on how their wealth had been acquired, just as poverty could not by itself reveal anything of the moral worth of an individual. There was no binding reason for a wealthy man to assume that his assets guaranteed his virtue; and no binding reason for a poor one to imagine that his indigence was a sign of depravity.

(Published from The Consolations of Philosophy with the kind permission of Alain de Botton)

Alain de Botton is a Swiss-born British philosopher and author. His books include Essays in Love (1993), How Proust Can Change Your Life (1997), Status Anxiety (2004) and The Architecture of Happiness (2006). He is also co-founder of The School of Life and a winner of "The Fellowship of Schopenhauer" annual writers' award.

Comments