Revisiting the forgotten facts of the Great War

History, more often than not, "is written by the victors". But, what could perhaps be even more universally accurate is that, "the first casualty of war is truth." Despite its great devastation and world-changing impact, the First World War is no exception to these age-old expressions; and neither is its commonly known history.

In his review of Gerry Docherty and Jim Macgregor's book Hidden History: The Secret Origins of the First World War, author Antony Black begins by writing: "Of the many myths that befog the modern political mind, none is so corrupting of the understanding or so incongruent with historical fact as the notion that the wealthy and the powerful do not conspire…They conspire continually, habitually, effectively, diabolically and on a scale that beggars the imagination. To deny this…is to deny both overwhelming empirical evidence and elementary reason." Later adding, "never [till WWI] were so many murdered, so needlessly, for the ambitions and profit of so few."

In 1904, the founding father of both geopolitics and geostrategy, Sir Halford Mackinder, proposed a theory that revolutionised geopolitical analysis, expanding it from the local or regional level to a global level. As journalist Joe Quinn explains, the majority of people, when they think of the world, visualise "a big, complicated place with billions of people." Whereas "elite" geostrategists, politicians and war-financiers, "think of a globe, or a map, with nation states that can, and should, according to them, be shaped and changed en masse." Accordingly, Mackinder separated the world into three parts: i) the "world island" (interlinking continents of Europe, Asia and Africa); ii) the "offshore islands" (British Isles and the islands of Japan); and iii) the "outlying islands" (Australia and the Americas). Among them, the most important by far was the "world island" for Mackinder; as whoever controlled its "heartland"—mostly Russian territory—would control most of the world's population and resources and, therefore, the world.

By then both the British and Americans were concerned about the close relationship between Russia and Germany, and France joining them in a triple anti-British alliance which they saw as a clear "threat to the international order" (John WM Chapman, Russia, Germany and the Anglo-Japanese Intelligence Collaboration). Britain thus signed an alliance with Japan in 1902, stipulating that if attacked, they would support each other militarily—essentially giving Japan the green-light to attack Russia in 1904, without fear of German or French interference as that would risk war with Britain. Russia's defeat to Japan a year later was secured firmly by Britain supplying warships and intelligence to the latter, and with British and American banks providing USD 5 billion worth of loans in today's value to Japan—including USD 200 million from prominent Wall Street banker Jacob Schiff, who also extended loans to the Central Powers later during WWI, despite his country (US) being at war against them.

The defeat, along with a financial crisis in Russia and threats from Britain, forced the Tsar to withdraw from the 1905 Treaty of Bjorko he had signed with Kaiser Wilhelm—and, by implication, France. A series of attacks launched against the Germans by the Russian press immediately after prompted the Kaiser to write this to the Tsar: "The whole of your influential press, have since a fortnight become violently anti-German and pro-British. Partly they are bought by the heavy sums of British money, no doubt." Such concerns among Germans only grew when the Anglo-Russian Entente was signed in 1907, and later, when France joined to form the "Triple Entente".

Meanwhile, the British public were openly bombarded by the British press with warnings of Germany's aggressive intentions to invade Britain and conquer the world. In 1912, a telegram from the Russian ambassador in Bulgaria to the Russian foreign minister identified a representative of the British newspaper, The Times, who claimed that "very many people in England are working towards accentuating the complication in the Balkans to bring about the war that would result in the destruction of the German fleet and German trade." The journalist, suspected to be James Bourchier, was deeply involved in the Balkan League that was established to lobby for the independence of Balkan states from the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires by the Russian ambassador in Belgrade, Nicholas Hartwig, who was on the British payroll (Hidden History: The Secret Origins of the First World War).

In the 1917 court case on the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand—commonly seen as the spark that ignited WWI—Serbian Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević confessed that he hired Ferdinand's assassins and that the murder was planned with the knowledge and approval of Hartwig and the Russian military attaché in Belgrade. Had this been revealed earlier, Britain would not have been able to justify going to war against the Central Powers. Nonetheless, all indications immediately after the assassination show that Austria only expected a local war to break out when it delivered its July 23 ultimatum to the Serbs. Even as the Russian and German armies were marching out of their barracks on July 1, the Tsar and the Kaiser were still exchanging telegrams to try and avert conflict. However, as things once more spiralled out of control, the Kaiser, later that day, wrote: "I have no doubt about it: England, Russia and France have agreed among themselves to take the Austro-Serbian conflict for an excuse for waging a war of extermination against us...the net has been suddenly thrown over our head, and England sneeringly reaps the most brilliant success of her persistently prosecuted purely anti-German world policy…a situation which offers England the desired pretext for annihilating us under the hypocritical cloak of justice" (Elmer Barnes, Genesis of the World War).

Yet another chance for peace appeared when the Kaiser wired Czar Nicholas a heartfelt appeal to negotiate the prevention of hostilities. Nicholas was so moved by Wilhelm's plea that he decided to send his personal emissary General Tatishchev to Berlin to broker peace. Unfortunately, Tatishchev never made it to Berlin, having been arrested and detained that very night by the Russian Foreign Minister, Sazonov, who was later found to have also been on the British payroll.

One of the great ironies of this "Great" War to protect the free world was that British and American arms manufacturers, many with links to the City of London and Wall Street banks, were arming all the sides in the conflict. The British-owned Armstrong-Pozzuoli Company, for example, was the chief naval supplier to Britain's enemy, Italy (GH Perris, The War Traders: An Exposure). In the British House of Commons, Labour MP Philip Snowden, once said angrily, "submarines and all the torpedoes used in the Austrian navy are made by the Whitehead Torpedo works... they are making torpedoes with British capital in order to destroy British ships" (HR Murray, Krupps and the International Armaments Ring: The Scandal of Modern Civilization).

Amidst all the chaos, the British and American governments also saw the perfect opportunity to stab the Tsar in the back, which they cynically did. In her book, Jacob H Schiff: A Study in American Jewish Leadership, Jewish-American author Naomi Wiener Cohen states: "The Russo-Japanese war allied Schiff with George Kennan in a venture to spread revolutionary propaganda among Russian prisoners of war held by Japan. The operation was a carefully guarded secret and not until the revolution of March 1917 was it publicly disclosed…the prisoners had asked him [Kennan] for something to read. Arranging for…a ton of revolutionary material, he secured Schiff's financial backing. As Kennan told it, fifty thousand officers and men returned to Russia [as] ardent revolutionists. There they became fifty thousand 'seeds of liberty' in one hundred regiments that contributed to the overthrow of the Tsar." Russian General Arsene de Goulevitch, who witnessed the Bolshevik Revolution first-hand, further confirmed that: "The main purveyors of funds for the revolution were neither the crackpot Russian millionaires nor the armed bandits of Lenin…[but were select members of] certain British and American circles" (Czarism and Revolution). Additionally, as author Jennings Wise reminds us, "Historians must never forget that Woodrow Wilson...[was the one who] made it possible for Leon Trotsky to enter Russia with an American passport" (Woodrow Wilson: Disciple of Revolution).

And as American journalist and labour organiser, Albert Rhys Williams, who was both a witness and participant to the October revolution, explained to the Senate Overman Committee in his testimony: "It is probably true that under the Soviet government industrial life will perhaps be much slower in development than under the usual capitalistic system. But why should a great industrial country like America desire the creation and consequent competition of another great industrial rival? Are not the interests of America in this regard in line with the slow tempo of development which Soviet Russia projects for herself?" When Senator Wolcott asked, "You are presenting an argument here…that if we recognise the Soviet government of Russia as it is constituted, we will be recognising a government that cannot compete with us in industry for a great many years?" Williams answered, "That is a fact…When the Bolsheviks started their first bank, Ruskombank, in 1922, one of its directors was Max May of Guaranty Trust. Guaranty Trust was a JP Morgan company. On joining Ruskombank, May stated: 'The United States, being a rich country with well-developed industries, does not need to import anything from foreign countries, but...it is greatly interested in exporting its products to other countries, and considers Russia the most suitable market for that purpose" (Anthony Sutton, Wall Street and the Bolsheviks).

What is most striking in relation to Williams' testimony is that, it was the same JP Morgan's Guaranty Trust that had raised loans for the German war effort; while simultaneously funding the British and French against the Germans; and the Russians also, both under the Tsar against Germany, and then the Bolsheviks against the Tsar for the "revolution" (ibid).

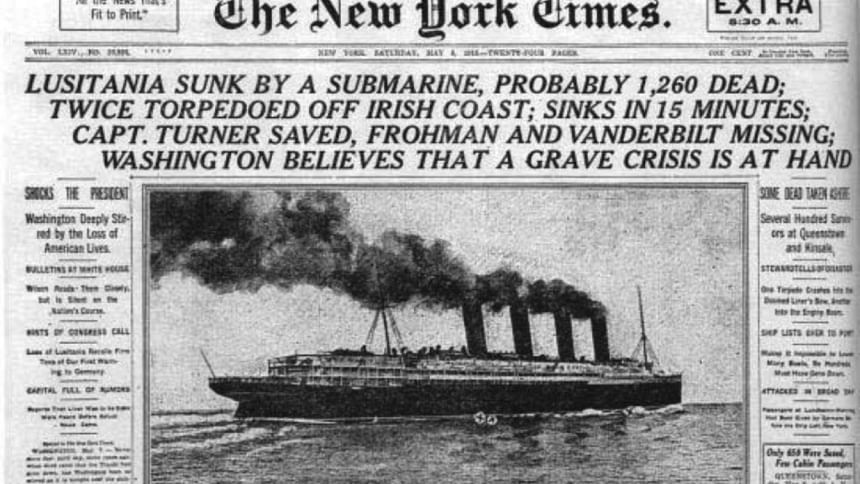

The incident that was to become the major catalyst for drawing a reluctant America into the First World War happened on May 7, 1915, when a German U-boat sunk the RMS Lusitania off the southern Irish coast, killing 1,195 people, including 128 Americans. "RMS" stood for "Royal Mail Steamer" which meant that the Lusitania was certified to carry the mail. However, in contravention of the rules of war at the time (Hague Conventions and the Cruiser Rules), it was carrying a considerable amount of ammunition, explosives, and other war materials for the French and British armies (G Edward Griffin, The Creature from Jekyll Island). This meant that the ship did not have the status of a non-military ship and could be fired upon without warning. The Germans knew that the Lusitania was carrying military supplies for its enemies. The German embassy in Washington even took the precaution of placing an advertisement in 50 US newspapers warning civilians not to sail on the ship. However, due to the intervention of the US State Department, most of these notices were not published.

At the time of its final departure from New York to Liverpool, Germany had declared the seas around the United Kingdom to be a war-zone and its U-boats were sinking 300,000 tonnes of Allied shipping every week. Winston Churchill, the Lord of the Admiralty, knew that German U-boats were operating in the area where the Lusitania was, after three ships had been sunk there in the previous two days. However, not only did he not come to its aid, but he ordered the Lusitania's planned escort, the destroyer Juno, to return to Queenstown harbour (British Commander Joseph Kenworthy, The Freedom of the Seas). Earlier, the Lusitania had been ordered to reduce speed by shutting down one of her four boilers (ostensibly to save coal). And the entire Admiralty knew that the Lusitania was a sitting duck, just waiting to be hit by the German ships.

At the beginning of the war, England and France had borrowed heavily from American investors and had selected JP Morgan to act as sales agent for their war-bonds. Soon Morgan became the largest consumer on earth spending around USD 10 million per day—being in the privileged position of buying, selling and producing for both sides. When the war began to go badly for England and France, Morgan found it impossible to get new buyers for the Allied war bonds. At one point, fear that England was about to lose the war crept into the Whitehall, and if the allies were to default, Morgan's large commissions would come to an end, his investors would suffer massive losses (around USD 1.5 billion) and his war production companies would be forced out of business. Fortunately for Morgan, the tragic sinking of the Lusitania happened only within a few days, dragging America into the war and allowing Morgan's war production companies to go into overdrive to outfit over four million American soldiers who now had to be mobilised for the war in Europe.

In 1925, Gerhart Von Schulze-Gaevernitz, a European theorist of imperialism, suggested that history would show that the most important result of World War I was not "the destruction of the royal dynasties that ruled Germany, Russia, Austria and Italy," but the "shift in the world's centre of gravity from Europe, where it had existed since the days of Marathon, to America." This new era of "superimperialism", he said, had turned traditional imperialism on its head because now "finance capital mediates political power internationally to acquire monopolistic control and profits from natural resources, raw material and the power of labour, with the tendency towards autarky by controlling all regions, the entire world's raw materials" (Antony Sutton, Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler).

As war-financiers made killer-profits from the deaths of millions of people and young men who were sent to fight in the Great War which they were told they had to fight in, for the sake of their family and their country, a strange event during the Christmas of 1914—known as the Christmas Truce—inspired American folksinger John McCutcheon to write these following lines:

'T was Christmas in the trenches, where the frost so bitter hung

The frozen fields of France were warmed as songs of peace were sung

For the walls they'd kept between us to exact the work of war

Had been crumbled and were gone for evermore.

My name is Francis Tolliver, in Liverpool I dwell

Each Christmas come since World War I I've learned its lessons well

That the ones who call the shots won't be among the dead and lame

And on each end of the rifle we're the same.

Eresh Omar Jamal is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star. His Twitter handle is @EreshOmarJamal.

Comments