Kahn's Journey to the National Assembly Building

What Einstein's E=mc2 is for physicists, Louis I Kahn's "Silence and Light" is for architects. Kahn's lecture on "Silence and Light" in 1969, five years before his death, was the recapitulation of his collective thoughts based on metaphysical reasoning that he considered a key to his point of view, applicable to all works of art, including architecture.

Louis I Kahn transformed as an architect when he built his first major design, the Yale University Art Gallery (1951-53) in New Haven, Connecticut. He received the commission while he was a resident scholar at the American Academy in Rome (1950-51). During that period, after visiting the ruins of ancient buildings in Italy, Greece and Egypt, he changed his approach to design and adopted a design principle based on the basics. Until that time, Kahn's mind was oscillating between two different streams of architectural thoughts. One was what he had learned at the University of Pennsylvania (1920-24), where the Ecole des Beaux Arts teaching method was based on French Neo-Classicism, incorporating elements from the Gothic and the Renaissance. The other stream was "Modernism" that pursued "order" and "universal" and based architecture on the abstract principles of design and rejected tradition and ornamentation. Creating new forms of expression and a unique aesthetic, Modernism emphasised function, simplicity and rationality. Alberti (1404-72) defined two conditions for architects: architect as a thinking man (homo cogitans) and architect as a craftsman (homo faber). Kahn was attracted to both conditions.

After graduation in 1924, Kahn gradually embraced Modernism because it contained the substance of liberalism and humanism. Although Kahn was experimenting with various aspects of Modernism, he was never content. Kahn realised why Cezanne, who participated in the Impressionists' exhibition, soon withdrew himself from there -- he was not convinced by the Impressionists' way of depicting a fleeting moment by focusing on changing light. Cezanne felt that the Impressionists were unable to capture the order and permanence of nature itself and, instead, became more interested in the permanent architectural qualities of the landscape. Like Cezanne, Kahn was also troubled by the visual lightness and floating character of the modernist architecture and instead was craving for an architecture that could bring back the sense of stability, permanence, and timelessness without losing the modernist abstract principles. With the design of the Yale Art Gallery, Kahn was able to establish an "alternate modernism" and that was the beginning of his transformation.

With the Yale Art Gallery, Kahn's works testify to a conviction in three entities: The Pantheon, the Pyramid and the Holocaust. For Kahn, the Pantheon was a place for contemplation, a place to transcend life. He realised in the Pantheon how the basic principles of architecture remained in the service of the ethical, moral and aesthetic spirit of human existence and how it transmitted the sense of wonder. With its oculus and the giant dome, the Pantheon epitomised a search for the divine that Kahn believed had always been and would always be. The Pyramid always fascinated Kahn for its primordial power, strong geometry, and enormous presence in the arid landscape with a sense of eternity. Human dignity was also of utmost concern to Kahn; he consistently aspired to enable his architecture in the reconstruction of the human dignity that was reduced to nothing during the Holocaust.

Kahn found primarily concrete and brick as his chosen materials in order to express the greatness of man-made space. The triangular stair within a cylindrical shaft in Yale Art Gallery (1951-53), Central Atrium in Exeter Library (1965-72) and the Assembly Chamber in Dhaka with a concrete paraboloid roof (1962-74) all belong to the Pantheon. In all these projects, Kahn reworked the oculus (the eye towards God) of the Pantheon to establish its timeless essence and relevance. The Pantheon has a grand illusive interior, whereas the Pyramid has a magnificent exterior. Kahn gained both in the Assembly Building in Dhaka, his most beautiful and glorious creation.

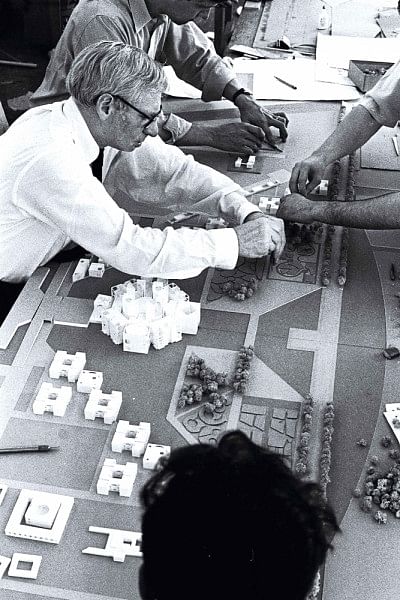

Kahn exercised his concept of 'served and servant' spaces first in the design of the Yale Art Gallery, and more explicitly in the Assembly Building in Dhaka. The core function of the Assembly Building is the Assembly Chamber, placed at the centre in a regular octagonal enclosure, lit by natural light from the roof. Eight wedge-shaped light wells are inserted within the octagon to provide natural light to the adjacent spaces on three sides of each of the light wells. Eight building blocks as servant spaces are placed around the central Assembly Chamber. Among them are the presidential entrance on the north, rooms for ministers on the west, dining and meeting room on the east, a mosque on the south and four rectangular office wings inserted among these conspicuous elements. The eight-storey high, ring-shaped ambulatory, extending from the ground floor to the ceiling, circles around the centrally located Assembly Chamber. The ambulatory is also treated as an urban street with light posts. The whole arrangement is articulated in a centripetal order towards the central chamber. As the intermediate zone, the ambulatory separates as well as unites the served and the servant spaces. Striped-configured glass blocks in the ribbed roof of the lofty ambulatory provide natural light. Instead of brise-soleil that was used by Le Corbusier in India to reduce heat, Kahn used thick walls, atriums and light wells in a subtle way to reduce heat entering the building.

In the end, fulfilling all functional requirements, the Assembly Building looks more like a giant abstract sculpture made of concrete since no door, window, and glazing are visible from the outside. The functional activities are all hidden in individual cells where light is provided indirectly. Circular, semi-circular and triangular punched openings in the side-walls are darkened due to lesser light, and an inconceivable atmosphere is created as if occurring in a dream. Similar conditions prevail all through the walkways, lobbies, ramps and steps. Kahn believed that an inspiring space can be created when light and silence together can produce an ambient threshold that can be realised and sensed.

The maze-like complexity and the ambiguity of space and forms are all achieved out of simple plan forms. The greatness of the National Assembly Building is indeed magical and thus unmeasurable. It has surpassed previous achievements in architecture and will probably remain unsurpassable in the future.

Shamsul Wares is an architect and currently a professor of architecture and Dean of the School of Science and Technology, State University of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments