Green initiative left in the lurch

Porimol Palma

When in 1981 the Food and Agriculture Organisation launched a green initiative in Savar and Chittagong's Rangunia to tackle pest attacks, farmers there had every reason to be relieved. It offered them help to fight off insects without using harmful pesticides.

Known as Integrated Pest Management (IPM), the initiative drew a huge response mainly for two reasons -- it was cheap yet effective and it reduced the negative impacts of chemical pesticides.

But the pilot project fizzled out in less than two years. Some 10 years later, the government in 1991 relaunched the programme in efforts to check rampant application of toxic chemicals on crops and vegetables.

More than two decades on, the government has been able to take the programme to the doorstep of some 20 percent farmers.

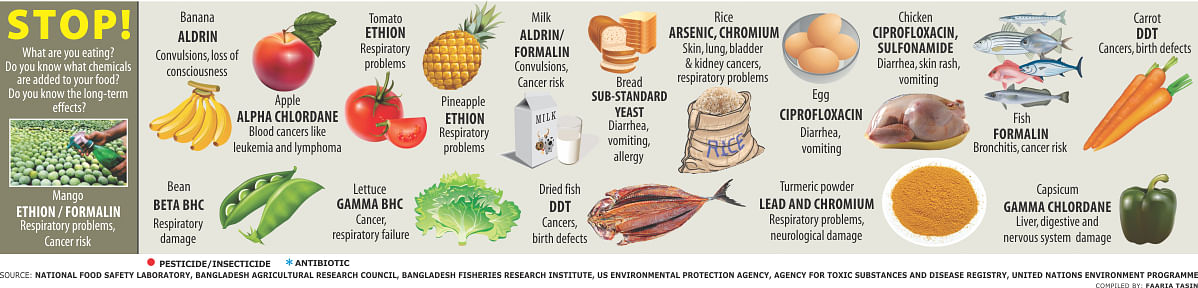

The pest control issue came to the fore amid growing concerns over food safety. Excessive use of toxic pesticides save crops, vegetables and fruits is blamed for much of the food contamination.

The Department of Agriculture Extension (DAE), which implements the programme, says it just does not have the money and manpower to take it to mass level.

But agro activists and other officials involved with the project say the government is not sincere enough to expand the IPM despite a growing demand for it.

Preventing pest attacks in ecological ways is part of IPM. Such an approach to pest control is vital for Bangladesh to check food contamination.

Of late, contamination and adulteration of food have become so widespread that lab tests by the Institute of Public Health last year found tainted about 60 percent of 10,000 food samples collected from the capital markets.

Also last year, a research by Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council revealed that nearly a third of the pesticides applied on fruits and vegetables is of substandard.

It is another reason why farmers apply excessive pesticides in their farms. While this practice pushes up production cost and leads to serious health problems, the IPM ensures chemical-free food, increases yields by 12-15 percent, cuts pesticide cost by nearly 70 percent and conserve biodiversity, said DAE official Mobarak Ali.

He is also director of the project called “Safe Crop Production Project Through IPM Approach”. There are some 26,000 IPM clubs of farmers to spread the pest control method under the project. Currently, 36 lakh of the country's 1.8 crore farmer households use the IPM.

This particular project began in 2013 with government funding and will end in 2017. Under the Tk 54 crore project, agro officials and farmers are being trained for using and spreading the IPM in 275 upazilas of the country's 64 districts.

“But the money and manpower we have are not adequate for a substantial expansion of the project,” Mobarak said.

Katalyst, an NGO, in a study on IPM in 2009 also found products and services required for its full expansion were insufficient.

“We want to use IPM, but often do not find pheromone in the market. Also, many local agriculture officials are not aware of it,” said Ayub Khan, a farmer of Bagharpara in Jessore who uses the method.

| WHAT IS IPM? IPM is a number of measures taken simultaneously to prevent pest attacks. The measures include: PERCHING: Small rods or sticks are planted for birds to perch on and eat insects. HAND PICKING: Farmers use hand nets to trap insects or set nets over the crops and vegetables to prevent insect attack. LIGHT TRAP: In and around the field, electric bulbs or lanterns are hung on a pole with water underneath. Attracted by the light, insects gather around it and drown. PHEROMONE TRAP: This trap has a capsule containing female sex hormone of insects. It is kept in a plastic bottle half-filled with water. It attracts male insects to flock to the bottle only to drown. Thus, mating and spread of pests are checked. |

Ashraf Uddin Ahmed, manager (business development) of Ispahani Agro Limited, said the Pesticide Act did not allow import of bio-pesticides like pheromone until its amendment in 2010.

Now only two to three companies, including his, can import and market it.

“Three or four more companies have applied for approval of eight other bio-pesticides, but those have been pending for about two years. The approval process of the DAE is very complicated,” he added.

“If more companies could import bio-pesticides and the DAE would not create any hassle, the IPM project could have expanded massively. It is the need of the day,” Ashraf said.

Asked, Mobarak Ali of DAE said research and field tests of bio-pesticides took some time. Moreover, the DAE does not have all the lab facilities and has to depend on Bangladesh Agriculture Research Institute.

“So, we cannot approve a product in less than two years,” he said.

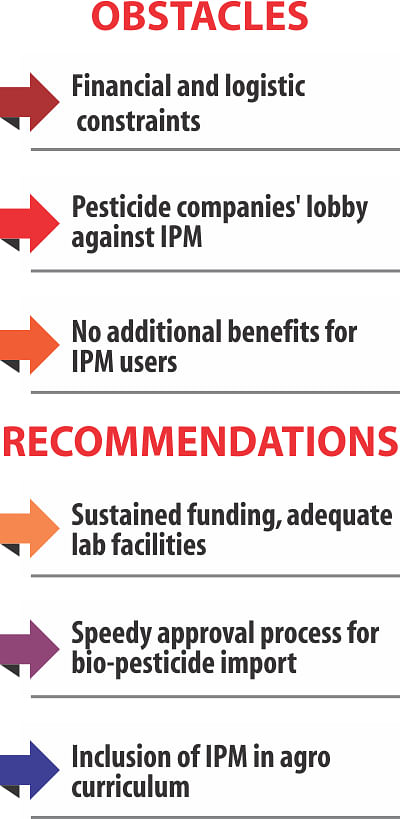

About the fund shortage, an NGO official said the DAE depended on donors' money for most of its projects. So when the donors stop funding, the projects suffer. In addition, chemical pesticide companies have a strong lobby that discourages the expansion of IPM.

But there are also factors that deter farmers from using the method.

Rezaul Karim Siddique, adviser of the Centre for Agribusiness and Competitive Strategies, said those applying the IPM were not getting any motivational price as their products were not differentiated from the food items produced with chemical pesticides.

“A certification system must be there for products produced under the IPM,” he noted.

Also, mainstreaming the IPM can keep crops, vegetables and fruits from chemical contamination. As a major step to this end, the IPM should be included in the curriculum of the agriculture universities, said Shamminaz Polen, senior business consultant of Katalyst.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments