The trap of call drop

No matter how much you grumble about that call suddenly going dead, the situation is unlikely to improve anytime soon.

Officially, only 5,193 complaints of call drop were lodged with the regulator last year, but industry insiders say it happens a few hundred crore times a year.

There are 15.7 crore active mobile connections in the country as of December.

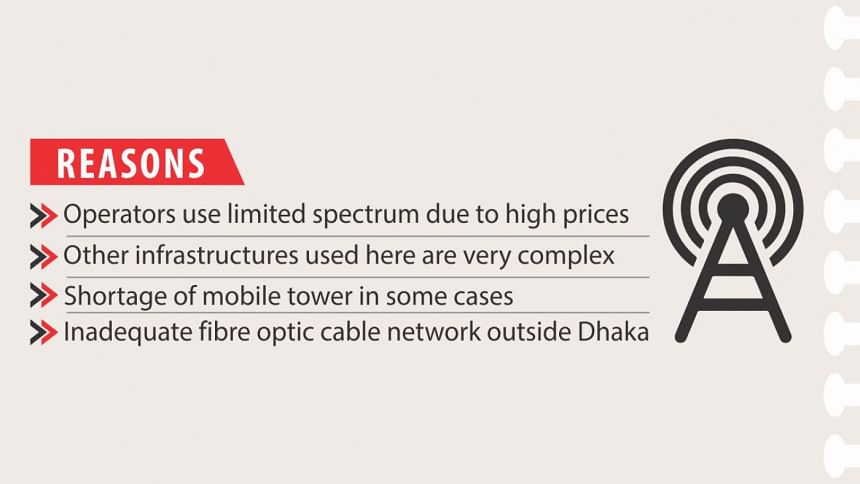

Call drops happen for many reasons, mainly technical. Key among them is the spectrum used by the operators.

In Bangladesh, mobile carriers use limited spectrum because of the unusually high price, the highest in the world. As a result, the network gets crammed, which in turn leads to call drop.

The situation is worsened by the strange arrangement of call transfers from carrier to carrier through independent gateways or interconnection exchanges (ICX), something not found anywhere in the world.

Across the globe, call transfers are done through radio links of the carriers. But here, it is done through 29 intermediaries (ICXs). Most of them are run by people with political clout, while a number of them are not properly equipped to handle the calls, industry insiders said.

Inadequate fibre optic cable network outside Dhaka also stands in the way of smooth call transfers. Shortage of mobile phone towers, which receive and transmit signals, are also to blame for the situation.

“Bangladesh is a unique country in the world in terms of mobile operators' network design, which contributes to sub-standard services,” said Abu Saeed Khan, a mobile industry expert, explaining the unnecessarily complex system.

HIGHEST IN THE WORLD

In Bangladesh, carriers use only 0.83 Megahertz of spectrum for every 1 million users, way less than what operators use in other countries.

Sri Lanka uses 6.21 MHz, Malaysia 5.19 MHz and Afghanistan 6.84 MHz for equal number of subscribers, according to GSMA.

Pakistan (0.95 MHz), Vietnam (1.33 MHz), Thailand (2.01 MHz), and Nepal (2.98 MHz) are also far ahead of Bangladesh.

During 2000-2017, frequency price in Bangladesh was almost three times the average price in Asia Pacific region. It is also the highest in the world, according to a study by the global association of the mobile operators, GSMA, published in July last year.

Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) sold every MHz of 900 MHz and 1800 MHz bands for $30 million and 2100 MHz band for $27 million. There was a 10 percent value added tax as well.

Some South Asian countries provide spectrum for free.

In February last year, only Banglalink and Grameenphone bought some additional spectrum. Still, their total spectrum is less than half of what they need for smooth operation, sources said.

BTRC Chairman Jahurul Haque acknowledged the high price of spectrum, but said it was due to the high demand.

Also, initially operators got free frequency when they started their business. That should be taken into consideration as well, he said.

“At this point, we can say that the government is seriously considering reducing the price, and the industry may see huge spectrum allocations in a short time,” he added.

JAMMERS, INADEQUATE TOWERS

In Dhaka city, there are at least eight spots, including Shahbagh and Mohakhali, where carriers cannot install towers due to inadequate space and other restrictions, resulting in call drops in adjacent areas.

Carriers cannot set up towers also in any defence officers' housing scheme (DOHS) areas in the capital. Authorities in Bashundhara Residential Area and Banasree also do not allow cell towers, said Shahed Alam, head of corporate and regulatory affairs at Robi.

The situation is similar in Chittagong, where mobile towers are banned in certain parts, including the port, DOHS areas and the airport areas, Shahed added.

“The use of unauthorised signal jammers is another concern for the operators as many mosques use them to stop phones going off during prayers. This causes call drops in adjacent areas,” he said.

Different authorities installed jammers from Bijoy Sarani to Jahangir Gate area. Powerful jammers have been set up in old central jail as well, he added.

In October, the BTRC issued a circular, asking people not to use unauthorised jammers.

WITHIN THE LIMIT?

Contacted, a chief executive officer of a top ICX operator shifted the blame on the mobile operators, saying the carriers were not investing enough.

In more than 95 percent cases, call drops happen due to call transfer problems for which mobile companies are responsible, claimed the official, who worked at a top mobile carrier for years.

Despite all these problems, a number of carriers claimed that their call-drop rate was within the limit set by the BTRC and that it was lower than the average limit in developed countries.

The BTRC's permissible call drop rate is 2 percent. Malaysia accepts up to 5 percent, and according to the International Telecommunication Union (a UN body), 3 percent call drop is normal.

The BTRC said they asked the carriers to improve their service quality to avoid facing action, including suspension of their service in certain areas.

Azizur Rahman, BTRC director of System and Service, said they were doing a survey to learn about the service quality.

“We will be tough on the carriers [if the service is poor],” he warned.

In a recent statement, Grameenphone, the largest carrier in the country, said, “While call drop is not an uncommon phenomenon in radio technology-based mobile services, the situation is more acute for operators in Bangladesh since we have many other players in the mobile phone value chain which are not under our control.”

Robi said high cost of spectrum, poor quality fibre network, complex telecom eco-system, challenges in setting up towers, and low average revenue were the main obstacles to providing the high-quality services expected from carriers.

“There can be many reasons for call quality or call drops and the majority of these are connected to external factors over which mobile operators have no control whatsoever,” said Shahed of Robi.

Also, in Bangladesh operators cannot establish their own fibre optic network, a fundamental resource for quality service, due to legal restrictions. This is why they have to get the service from third parties, he said.

Currently, there are five players in the fibre optic cable business. Three are state-owned and they have very small networks. The two private ones virtually have a duopoly of the business.

BTRC Chairman acknowledged the challenges facing the carriers and said the problems could not be solved overnight. “It will take five years to solve this.”

He said the carriers must buy more spectrum. In the meantime, the telecom watchdog would try to mount pressure on them to improve service quality and reduce the number of call drop.

Based on customers' complaints, the BTRC recently asked the carriers to update them about the latest call drop situation, he added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments