Fathoming ICT (Amendment) Act, 2013

How times and contexts change! Let us take stock of the following:

According to Article 39 of the Constitution of Bangladesh,

“(1) Freedom of thought and conscience is guaranteed and (2) Subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interests of the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to an office:

(a) the right of every citizen to freedom of speech and expression; and

(b) freedom of the press, are guaranteed.

Amendment 1 of The Constitution of the United States affirms that, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Finally, as Robert McChesney tells it, “To paraphrase the immortal words of Thomas Jefferson, if a society could have either media or government, but not both, the sane choice for free people is media.”

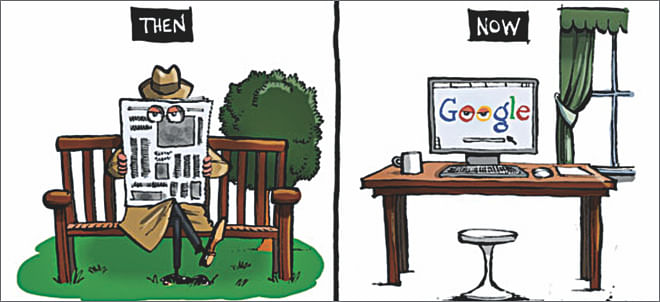

The American constitution, ratified in 1788, is the oldest written national constitution in use, while its First Amendment, one of ten amendments that make up the commonly termed Bill of Rights, was adopted in 1791. Jefferson, considered by many authorities as being among the greatest of American presidents, was the primary author of the US Declaration of Independence. The documents mentioned were composed, and Jefferson made his remark, more than two hundred years back. The Bangladesh constitution, by comparison a juvenile, came into being only forty two years and a bit ago. What they all have in common, in the context of this discussion, is that all existed, or had come into being, before the onset of the Age of the Internet. Although Canadian communications theorist, visionary, and educator, Marshall McLuhan, famous for his maxim “the medium is the message”, had predicted that the combined influence of television, computers, and other electronic information dissemination would influence styles of thinking and thought, whether in art, science, religion, or sociology, none could have realistically imagined the degree of potency of the clout that the Internet would bring to bear on the nations and people of the world. In fact, the World Wide Web (www) has been instrumental in the evolution of the term 'globalization' in the Age of the Internet.

However, www (also labeled Wild Wild Web by doubters and concerned scholars alike) carries within itself the potential to do mischief as much as the ability to do great good. That capacity to cause real or potential harm in quick time to a vast number of individuals, society, and governments has, at times, and in various degrees, placed it at loggerheads with national governments. Many in the academia and outside of it believe that, just as the wild wild west was eventually tamed, so will the world wide web (alternatively, wild wild web), but the process will take time, since policymakers and experts are still grappling with its multifarious ramifications for societies and individuals. Powerful countries and their governments have been at the receiving end of cyberspace machinations or revelations, as the specific cases may be. WikiLeaks disclosures might have provided the media (and, it must be remembered that the Internet is part of the new media) and interested people across the globe a field day in becoming conversant with classified government material, especially those of the powerful countries, but the affected governments have been

incensed, resulting in Julian Assange being holed up in the Ecuadorean embassy in London (and being given diplomatic asylum), and Private Bradley (subsequently Chelsea after identifying as a trans woman) Manning being sentenced to a lengthy term of imprisonment (35 years, with the possibility of parole in 8 years) in the US. Then the saga of Edward Snowden, who has ruffled a good many powerful feathers in several powerful capitals, has had diverse effects. They include indignation in the heads of government of Germany, France, and Brazil, among others, against the allegations of spying against them by US and British spy agencies, and uproar in the US that one of their own had carried out the act!

Almost inevitably, the Internet has also affected Bangladesh, its governments and the people. Successive governments have sought to control it through the enactment of laws and amendment in the Jatiyo Sangsad. And, that, again expectedly, has given rise to protests and indignation from various quarters of the country. Towards the end of its tenure in office, the last BNP-led government promulgated the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act of 2006. One of its provisions was punishment for a maximum of 10 years for committing cyber crimes. Then, following cabinet approval of the draft on 19 August 2013, the Awami League (AL)-led regime, through an act of parliament, passed the ICT (Amendment) Bill 2013 on 6 October of that year.

And, just as inevitably, voices have been raised against the Act and its Amendment for, among other possible negative outcomes, compromising democracy, curbing human rights, and infringing on freedom of expression, specifically that of freedom of the press. They have been particularly concerned about Article 57, part of which reads: “…any willful release on websites or any other electronic platform of any material which is false, vulgar, defamatory, liable to cause deterioration of law and order, or tarnishes the image of the state or individual, or hurts religious sentiments is treated as a cyber crime.” That brings us to the issue of the stipulations of, first, cyber crime being a non-bailable offence, and, second, law enforcing agencies being able to arrest, without issuing any warrant, any person suspected of committing cyber crime. Both have serious implications for constitutional rights, including freedom of expression.

Obviously, the proviso of not requiring a warrant for arresting someone, even if just on the suspicion of having committed a crime, and then making the offense non-bailable, contravene basic human rights as stipulated by the Bangladesh constitution. And, because the Internet is also known as the new media, distinct from, but complementary to, the traditional media represented primarily by printed newspapers, magazines, cinema, and television, strict regulations imposed on it may also be construed as curbing freedom of expression and of the press, both of which are guaranteed under Article 39 (a) (b) of the constitution. However, the Act invokes the old reliables, security of the state and deterioration of law and order situation, to justify its severe provisions. And, of course, Article 39 specifically mentions “in the interests of the security of the State” as being a rationale for restricting freedom of speech and expression, or of the press, or both.

Amendment I of the American constitution does not contain any qualifiers to freedom of speech and of the press. In fact, Amendments III, IV, V, VI, and VIII take particular care for protecting the rights of individuals, including those accused of having committed a crime as well as those convicted. However, the caveat must be introduced that American and Bangladeshi societies are different from each other in several ways, and it would be unfair to Bangladesh to judge it strictly against American values and traditions. Not only are there marked differences between their societies, values and traditions, but also the character of the people who constitute those societies, and fashion those values and traditions, are also dissimilar in important ways. The Americans, with the Supreme Court, as the country's judicial guardian and armed with the power of judicial review (a doctrine not constitutionally apportioned to it, but one it has taken upon itself following its disposition of the Marbury v Madison case), acting as an alert custodian of the constitution, are usually quick to safeguard their constitutional rights. The US constitution is a sacrosanct document whose amendment is a truly onerous process.

In fact, the US Congress had tried to set the Internet in order when, in 1996, it enacted the Communications

Decency Act (CDA), which aimed at regulating both obscenity and indecency (when children are exposed to it) in cyberspace. However, in the 1997 case of Reno v ACLU, the US Supreme Court found the anti-indecency provisions of the Act to have been unconstitutional (invocation of judicial review here). Writing on behalf of the Court, Justice John Paul Stevens spelt out both constitutional sanctity and right to freedom of speech: “the CDA places an unacceptably heavy burden on protected speech.” While the free speech provision of the Bill of Rights prevent federal, state, and local governments from directly censoring the Internet, obscenity, including child pornography, does not enjoy First Amendment protection. The same constitutional amendment also allows Americans to burn their own country's flag within the US without incurring any penalty (an action that would be sacrilegious in Bangladesh), an act that was also judged to be constitutional, if repugnant, by the Supreme Court. In the US, the Supreme Court undertakes judicial review to protect the spirit, as much as the letter, of the constitution. In Bangladesh, we often use the constitution to suit our own particular agenda or ideology.

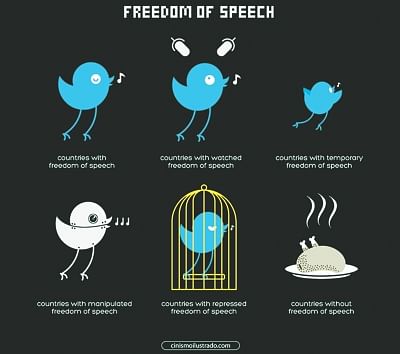

The problem with cyberspace or the virtual world is that there is no precedence for cyber laws. Cyberspace is by nature global, knowing no boundaries, unless imposed by a government. The paradox here is that, shutting down the Internet might serve the interests and agenda of a particular government, but it would also greatly isolate it and the country it governs from the rest of the world, with multifarious negative consequences for both. We live in a world of participatory media and culture. We have essentially moved from a one-to-one to a many-to-many mode of communication. The Internet is a potent medium for democratic communication and action (some ending in successful outcomes, as, for example, in the Arab Spring, and others in failure, also in the Arab Spring!). It bypasses the popular websites like Wikipedia, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. Its problem is that it is misused by irresponsible people, and that provokes, or invites, essentially various kinds, and degrees, of censorship on it. In the process, freedom of speech and of the press (especially as the Internet is new media) are often severely curtailed as regulations are brought to bear on the new media users.

In Bangladesh, the political culture is in such dysfunctional a state that the provisions of a piece of legislation might easily be extended to cover people not understood to be within the parameters of the Act. It has happened before, and, if it does again, very likely would result in the kind of vicious political animosity that the country does not need. Internet governance, that is, restricting or controlling access to certain information, cannot become a tool for muzzling of dissent, of the right to air one's views as long as they do not bring harm to an individual or country, and of the right to inform people of the facts, however unpalatable they might be to groups, large and small, and individuals. Times and contexts have changed. Cyberspace is a completely new domain that has understandably given policymakers and pundits much headache. Different countries have tried to tackle the problem in their own ways.

The People's Republic of China has enforced some forms of Internet censorship, and in 2013, announced the detention of hundreds of people accused of spreading false rumours online. China's reasoning for arresting cyberspace users bears strong resemblance to Bangladesh's ICT Act: information that “breaks laws or spreads superstition or obscenity” or that “may jeopardize state security and disrupt social stability” are subject to prosecution. Beijing believes that the enforcement or threat of enforcement of Internet censorship encourages self-censorship of politically unacceptable messages. Whether that is the case is for China to experience, but it is not the only country that imposes some form of restriction on the Internet. In its 2012 report, Reporters Without Borders, an organization that promotes and defends freedom of information and freedom of the press, listed 12 countries as Enemies of Internet, including China, Cuba, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and North Korea. It also listed 14 others as Countries under Surveillance, including some that are surprising: Australia, France, India, Malaysia, Russia, South Korea, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Turkey, and UAE. Bangladesh does not feature in either.

And nor should it. The problem is that playing the mirror imaging game, of upping the political ante, threatens Bangladesh to be conceivably included in one of the two categories, besides landing the country in a political quagmire. The 2006 Act, promulgated by the BNP-led government, has been given an added twist, while keeping intact its fundamentals, by the 2013 ICT Act (Amendment) engineered by the AL-led government. The danger is that such spiraling might signal more of political gamesmanship than a serious attempt at understanding the ramifications of cyberspace. Freedom of expression and of the press cannot be sacrificed to political dysfunction. As of this writing, we are faced with the prospect of finding our way through a minefield of prospective curtailing of freedom of speech and of the press, especially, to reiterate, as the cyberspace is the new media. And that cannot be a cheerful prospect.

The writer is educationist, actor, former diplomat.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments