‘The Green Knight’ adaptation subverts the tenets of chivalric romance

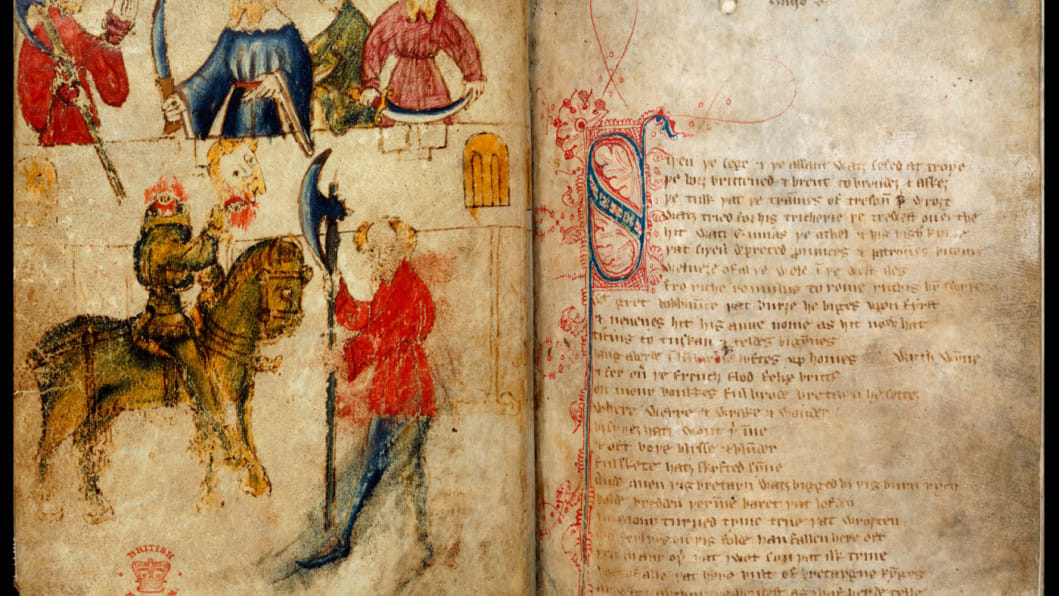

The mystical riddle that was the film, The Green Knight (2021), was initially just that for me: a riddle. It was one of those films where I felt like my experience of watching it would be more rewarding if I had some idea of the actual story it was based on. As I read through Sir Gawain and the Green Knight—an alliterative poem, written circa the 14th century, in a Middle English dialect by an anonymous poet—I realised it was the kind of endeavour that neither my very short attention span nor my patience was ready for; yet I already felt challenged. Being a folklore junkie and not coming across an epic about King Arthur's nephew and heir apparent? Nope, couldn't let that blot my escutcheon.

The poem starts with Britain's bloody and make-believe history. The poet then proceeds to tell of a tale he had heard about King Arthur and Sir Gawain, Arthur's nephew and the youngest of the Knights of the Round Table.

During one Christmas celebration at the court, King Arthur demands to hear a marvellous story before he can feast. As if on cue, a giant knight rides into his court in emerald green attire. Not only his clothes, even his skin and his horse are green. This being lays down a challenge for whoever is brave and quick: he declares that a man from the court should strike him with his own axe, which he shall endure without fighting back. The catch, however, is that in a year and a day, he will strike the same blow to the contender in return.

Acclaimed director David Lowery's film opens with Gawain (played by Dev Patel) romancing Essel (Alicia Vikander), a commoner, in a brothel; only he isn't a knight—yet. The muted tones in this first scene, the heavy stone architecture, and the pale makeup of the characters along with velveteen, ornate costumes of greens and browns capture the rotting ambience of the medieval era. In Dev Patel's flawless rendition, Gawain becomes a gullible and befuddled youth, his naivety and youthful impulses offering a solid ground for the plot to rest upon. However, commoners and people of the court glorify this rather unseasoned knight-in-making because he is nephew to King Arthur.

A point of contention with the source material here is that in the poem, Sir Gawain is aware of his inferiority and incompetence compared to the other knights. He is also said to be shy, cowardly, and morally rigid; the entire point of the quest he embarks upon is to test his courage and virtue. In the film, Gawain comes off as a drunk and a reckless womaniser. When the Green Knight lays down his challenge, Gawain's inclination to oblige comes off more as an act of foolhardiness. While the original poem is a chivalric romance, intended to represent a knight's valour and character arc through tests that challenge his moral and ethical values, the film thus steers more towards a bildungsroman, playing with the internal evolution of Gawain's conscience rather than depicting a dated idea of morality and courage. It offers a more postmodern, grey protagonist who subverts the tropes of righteousness and valour of traditional epics like Beowulf and Odyssey.

This subversion is extended further in the way in which Gawain tries to survive the challenges in his journey. But while it succeeds in fleshing out the juvenility in Gawain's character, it causes the screenplay to lose context in some instances, particularly in its handling of the character of Gawain's "witch" mother, Morgana Fay (played by Sarita Choudhury).

Ultimately, I appreciated that the scope of interpretation was subjective and I greatly enjoyed the subtleties of these implications. The pacing, however, (irrespective of the intervening research), was frustratingly slow for me. The ending was perhaps the saving grace—the grandeur of the visuals, the big plot twist, the brief peak into the Green Knight's beautiful green cathedral, his sudden cheekiness— they all had the potential to create an immensely gripping film, but the expositional details, as subtle and exciting as they were, were unevenly bunched up in the last 30 minutes or so.

I had almost forgotten my staunch loyalty for keeping to the source material by then. I wish the entire film had been just as gripping.

Maisha Syeda is a writer, painter, and a graduate of English Literature and Writing.

For more book-related news and views, follow Daily Star Books on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments