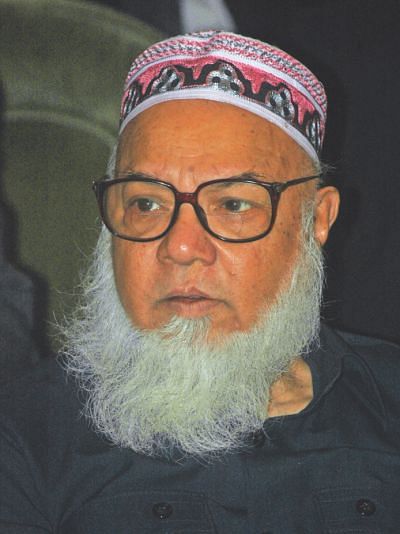

Chief Justice Mustafa Kamal -- Iconic legal giant of bygone age

Chief Justice Mustafa Kamal is one of those rare academic-minded lawyers who never lost his zeal for judicial activism despite the elevation of age or status. I have had the pleasure of interacting with him quite intensively soon after my return from the United Kingdom in 1995. I haven’t had the privilege of appearing before him as a practicing barrister but my encounters happened as the founding executive director of TIB. A core activity of TIB, since its inception, has been to examine the causes and symptoms of poor service delivery of national institutions. Judiciary was one of them that came under close scrutiny, and I won’t be exaggerating if I said that at the risk of being charged with ‘contempt’ TIB started putting various research findings on the judiciary in the public domain from the year 1997. Sadly, they revealed embarrassingly low level of public satisfaction, particularly when it came to the lower judiciary. As TIB was advocating for improved governance, Justice Mustafa Kamal was exercising his judicial mind to call for an independent lower judiciary or redefining the limits of locus standi in relation to writ applications. Justice Mustafa Kamal’s famous cases, such as, MasdarHossain and Dr. MohiuddinFarooque, among many others, will remain as rich testimony to Justice Mustafa Kamal’s judicial activism.

In the case of MasdarHossain Justice Mustafa Kamal laid out a clear roadmap for the separation of the lower judiciary from the Executive. The boldly delivered landmark decision of Secretary, Ministry of Finance v MasdarHossain (1999) became the rallying call for various civil society organizations and media houses to pursue the objective of an independent and accountable lower judiciary in Bangladesh. Justice Mustafa Kamal had to determine the position of the judiciary vis-à-vis both the executive when in 1995 a group of judicial officers brought before the court the following constitutional issue – to what extent the Constitution of the Republic of Bangladesh has ensured the separation of judiciary from the executive organs of the State. In other words, it fell on the sharp intellectual acumen of Justice Mustafa Kamal to extensively examine the Constitution of Bangladesh to determine whether the Executive has followed the provisions of the Constitution. It is pertinent to mention here that Justice Mustafa Kamal had delivered a number of lectures on the constitution of Bangladesh, which was subsequently published as a book, Bangladesh Constitution: Trends and Issues in 1997.

Justice Mustafa Kamal delivered his historic judgment with 12 directive points on 7th May 1997 (reported in 18 BLD 558). The Government appealed and the Appellate Division upheld the decision of the High Court Division but with some modification. The judgment was delivered on 2nd December 1999 (reported in 52 DLR 82), and the Government was given clear directions in order to complete the process of separation of the lower judiciary from the executive by undertaking steps, such as, a separate Judicial Service Pay Commission, amendment of the criminal procedure and the new rules for the selection and discipline of members of the lower judiciary. Civil society organizations and print and electronic media joined hands with others and after a long period of political procrastination the implementation started in 2007. After his retirement Justice Mustafa Kamal continued to advocate this cause, and on many occasions he spoke boldly on the reluctance of the executive to implement the directives of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh.

The fact that Justice Mustafa Kamal didn’t choose to become a private man, secluded from the challenges and controversies of everyday life, is manifested by his active participation in various conferences, seminars and roundtables. Dhaka is famous for its ‘adda’ culture and lately the talkative Bengalis have formalized this into regular roundtable meetings of the ‘usual suspects’. Justice Mustafa Kamal didn’t shy away from these gatherings just because he once occupied the rarified benches of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh but selectively attended them and expressed his opinions with judicious balance and objectivity.

I recall with great satisfaction Justice Mustafa Kamal’s consent to attend the 9th International Anti-Corruption Conference (10th to 15th October 1999), which was held in Durban, South Africa. Chief Justice (as he then was) Mustafa Kamal became the de facto leader of a rather large contingent from Bangladesh on the invitation of Transparency International. Justice Mustafa Kamal was invited to address a plenary session, and at the end of the speech he received a standing ovation! He delivered a powerful speech, ‘Ethics, Accountability and Good Governance’ (http://iacconference.org/en/speakers/details/mustafa_kamal/).

Let me cite a few paragraphs:

…if corruption is to be combated, it would have to be addressed both by way of a change of heart and a change of consequences. Thabo Mbeki, president of the republic of South Africa, aptly put the question to the audience on the opening day of the conference: the generation that follows you, what will be your message, mere attainment of material success and prosperity by fair means or foul, or the attainment of a spiritual stature that will transcend material over fulfilment?....

Good governance, ladies and gentlemen, is an extension of the principle of the rule of law. A society is well governed when there is a rule of law, not a rule of man or woman. A modern state is extensively governed by rules and regulations, by complex guidelines and instructions, by a web of regulations, restrictive, prohibitive and penal procedures. As a fish starts getting rotten from the head, good governance starts sliding from the hands of the people when the top people in parliament, executive and judiciary put rules and regulations aside and start ruling by the rule of the thumb. A democratically elected government is not necessarily a democratic and open government. It has often been found in history that a democratically elected government can also be despotic and autocratic in practice. The external world is satisfied if the adults entitled to suffrage go through the motion of voting at intervals, but little do they realise if these periodic exercises have made any difference in the manner and quality of governance.

On his retirement in 1999 Justice Mustafa Kamal took on alternative dispute resolution, popularly known as ADR, as his cause celebre. He travelled extensively up and down the country to raise awareness and conducted training on ADR. Given the fact that there are millions of pending cases in the courts, Justice Mustafa Kamal rightly believed that one of the most effective ways of dealing with this perennial and pernicious cause of misery to citizens, particularly the poor, was to formalise a citizen-friendly mechanism to resolve minor disputes of mainly civil nature outside the realm of the formal justice sector. His effort was subsequently vindicated when the Government of Bangladesh enacted a new law, which has made the use of mediation and conciliation mandatory before resorting to courts and lawyers.

Justice Mustafa Kamal’s intellectual honesty and integrity has opened our ‘eyes’ to the real weakness of the judiciary and the legal profession. Rather than delivering justice to the citizens of Bangladesh the long delays and lowering of ethical standards have brought much frustration among the public, and it is high time that we come up with alternatives.

Justice Mustafa Kamal and what he embodies is fast disappearing from our society, a sad but incontrovertible observation.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments