Capturing a turbulent chapter of history

War is a difficult time. Chaos reigns supreme, and nobody knows what's going to happen the next moment. As bullets and bombs fly through the air, anybody could be in their path, and no one seeks explanations. The first instinct is to survive; to get to safety. And that is what makes documentations of such events such a daunting task. But at the same time, any war has repercussions in many layers; it's not just what appears from the outside at a first glance. From the very big picture to zooming in on a single family unit, every war has a million stories folded in them, and it is thus only that much more difficult to bring out a clear picture.

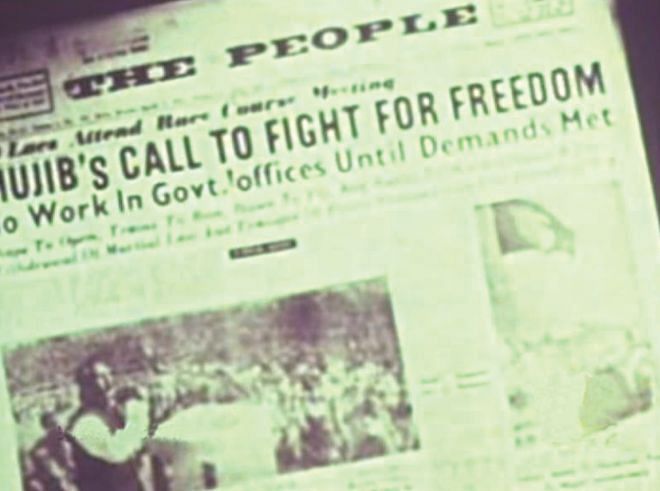

In 1971, when the occupational Pakistan army attacked Dhaka, and spread around to all parts of the country in a spree of mindless genocide, technology was at a different place altogether. Photo and video equipments were not available just anywhere, and the risks associated were countless. But still, there were those who fought against the odds, and captured the atrocities. Zahir Raihan's “Stop Genocide” was one of the first documentaries made on the attack of 1971; his other film “A State Is Born”, Babulal Chowdhury's “Innocent Millions” and Alamgir Kabir's “Liberation Fighters” are considered the first films made in Bangladesh. Indian filmmaker S. Sukhdev made “Nine months to Freedom” with a lot of footage he shot himself during the war and in refugee camps, craftily depicting the misery that the people of the country had to go through. Gita Mehta, a war correspondent of US TV network NBC was also on assignment in Bangladesh during the war, and with what she saw and captured, made another powerful documentary titled “Dateline Bangladesh”.

Right after the war, a number of feature films were made on it, but it was still challenging to make documentaries on the war, because of a lack of technology and especially footage. But as days went by, a few of the country's most gifted filmmakers stepped forward in leaving visual documents for future generations of what happened in 1971, on the ground and beyond. Tareque Masud and Catherine Masud discovered footage taken by US filmmaker Lear Levin in his basement, recovered them and used them to bring out another touching picture of the war; the “Bangladesh Mukti Shangrami Shilpi Shangstha” that went to Freedom Fighters' camps and sang songs to bolster their morale. The duo also made two other documentaries, “Mukti'r Kotha” and “Nari'r Kotha”, as part of the series.

However, it is Tanvir Mokammel's epic documentary “1971” that is the most elaborate document of the Liberation War, spanning over three hours in duration. He has two other documentaries on the war: “Swopnobhumi” and “Smriti Ekattor”.

Apart from these, many filmmakers have attempted to portray their interpretations of the war from compiled videos, and collections of video footage and pictures have been archived on the internet, most notably by Bangladesh Genocide Archive (genocidebangladesh.org); among private researchers, Omi Rahman Pial has an enriched video library on Youtube featuring many rare footage and interviews.

No one is born with patriotism. But Bangladesh has a glorious past, and everyone born in the country deserves to know what great pride they have to hold. It's said that history is easy to distort, but in this age of information, if someone does intend to find out the true history of the Liberation War and the struggles beyond, these documentaries can possibly be the most powerful resources. Most of them are available on DVD/CD, and those that are not can be accessed on the internet. More than anytime since the birth of Bangladesh, the youth of today require to go back to these films, be aware, and spread the awareness and spirit.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments