How can we prevent trade-based money laundering in Bangladesh?

The budget for fiscal 2020-21 has proposed to impose 50 per cent penalty on misdeclaration of exports, imports and investment in foreign countries. This seems to be a sound proposal from the revenue point of view.

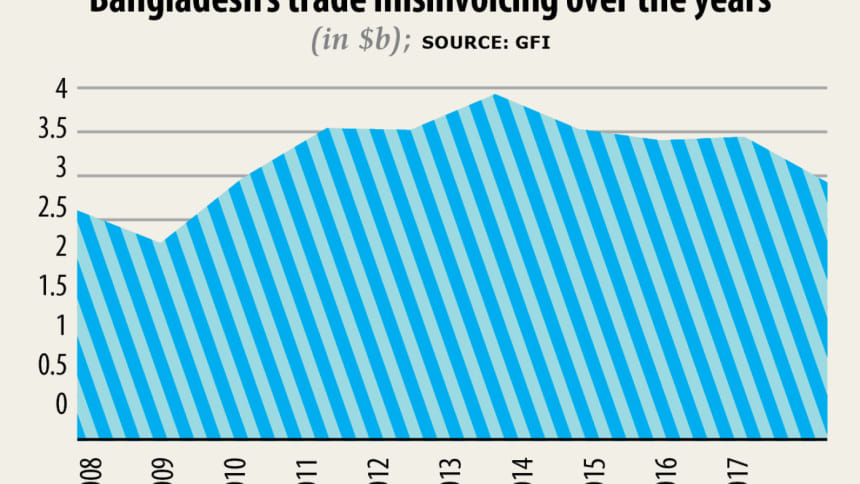

Global Financial Integrity report ranks Bangladesh as one of the top countries facing trade-based money laundering (TBML), which is a significant threat to growth and sustainable development.

This is because there is a rapid expansion of international trade.

According to a report of Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB), some $3.1 billion, or Tk 26,400 crore, is being illegally remitted from Bangladesh a year.

This syphoning of money is depriving the government exchequer of about Tk 12,000 crore as revenue a year.

Now the pertinent questions are: what is misdeclaration and how to impose a penalty on misdeclaration?

Unfortunately, we don't have any study on TBML in Bangladesh. This article underscores the need for such a study and attempts to outline it.

The main objective of the proposed study may be to assess the potential of matched customs and central bank data to (1) detect suspicious international trade transactions, and (2) quantify the extent and characterise the nature of TBML.

The methodological approach may be based on the following aspects:

· The combined use of bank and customs records constitutes a rich base of information to detect illicit trade flows, relative to using trade data alone.

Using the information on financial regulations and customs procedures, the detection of suspicious transactions can be done without imposing an a priori hypothesis on the mechanism or motive for money laundering.

Statistical analysis for fraud detection can be performed on both sides of the transaction -- the flow of goods and the flow of payments.

The letters of credit (LC) may be categorised as non-suspicious, suspicious or undetermined. Non-suspicious observations correspond to LCs that do not seem in breach of existing regulations nor they exhibit any abnormal pattern. Suspicious transactions are those that exhibit features that could be strongly indicative of abuse to the customs system. Undetermined transactions are those that cannot be categorised as unequivocally suspicious.

For convenience, we can label the three categories of observations as white (non-suspicious), black (suspicious) and grey (undetermined). In the white category, there is a match between the import data and LC settlement data. In black (suspicious) category, we flag suspicious LCs for which total payment exceeds significantly the amount associated with customs records, and for the grey (undetermined) category, we identify a large set of sub-categories that can be deemed as undetermined (a transaction that cannot be categorised as unequivocally suspicious).

The research design contemplates a number of steps.

First, a small survey may be undertaken to collect qualitative information on the perception of stakeholders and relevant public officials on the nature, extent and motives of TBML in Bangladesh.

This will serve the purpose of a better understanding of the expectations and needs of the partner organisations, as well as focusing on specific lines of enquiry when analysing the data.

Second, the sample of customs records will be matched with the sample of LC, using the identification number of LCs.

Third, a number of operational definitions may be formulated to detect different types of suspicious shipments and/or suspicious LCs, based both on the bank and customs records. These operational definitions are to be discussed with the relevant public officials.

Fourth, based on the identified suspicious transactions, we may use machine learning techniques on variable selection to back-out the regular patterns associated with potentially illicit trade and bank flows.

Fifth, we will repeat the identification exercise using fraud detection statistical techniques that do not require explicit operational definitions of fraud, to extract additional regular patterns.

We can make a comparison between observed unit values in the customs records and international prices.

However, this is typically only useful in product categories that are highly homogeneous and on sequences of prices that span a long time period. It is proposed to be included when transactions on both export and import sides are available and the data can be extended over a few years, such that price series are rich enough.

An analysis of anomalies in shipments and LCs, according to their types (sight LC, deferred LC, irrevocable LC, etc.) may be useful as well.

Indeed, we believe this is a very important dimension of analysis. It is crucial to use taxes (import or other) to identify differences in anomalies across product categories and over time.

However, one year of data is insufficient for this type of analysis, as the only variation that is left in tax rates (in best case scenario) is across products only, which is often conflated with the other very relevant characteristics of different product codes.

We suggest performing this analysis with data that spans over multiple years only.

Exploiting cases that correspond to LCs that are settled, but no bill of entry is submitted. This is indeed very relevant and some of the flags that identify suspicious observations address this case.

However, the censoring that comes from the time span of the data limits the statements we can make on this dimension.

The instruments to be used for the study are bills of imports and exports, bills of lading (NBR) and LC opening and settlement (the Bangladesh Bank), which are available online.

Real-time data for five years may be used for the purpose.

The author is a professor at Brac Institute of Governance and Development, Brac University and former chairman of NBR

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments