Budget 2014-15: Need for reforms in ADP

THIS year, the finance minister has already kicked off pre-budget discussions by formally indicating the size of the upcoming budget and holding several rounds of meetings with external stakeholders, viz. scholars and civil society. In fact, a budget of Tk. 2.5 trillion in the fiscal year 2014-15 would remain far behind the projection of Medium-Term Budgetary Framework (MTBF), which raises question of its credibility in terms of both forward baseline estimates and achievement of budgetary goals.

There are big challenges of attaining the growth target set in the Sixth Five-Year Plan and even in the outgoing budget. The World Bank's projection is even lower that the government's pessimistic projection, while we see a tug of war on revised size of Annual Development Programme (ADP). Indeed, ADP is widely regarded as instrumental to achieve higher growth, especially when large public investment is required to recover from political ravages in the last year. At the same time, we must reform through transition from traditional low-return ADP to a more systematic and high-impact multi-year public investment programme (MYPIP).

Why do we need an MYPIP although the projects are multi-year in ADP and the MTBF are also showing the individual projects by ministry, division and agency (MDA)? By now we have faced quite a lot of difficult questions on the consumption of resources, return, and disgrace of ADP that is even termed as a 'black hole.' What factors led to such a miserable performance of ADP over the years?

Three major elements can be identified by looking into it carefully. First, it has become a leviathan with a thousand projects approved and nearly eight hundred unapproved but kept in 'Green Pages' with possibility of getting green signal from Ecnec anytime in the fiscal year. There are quite a large number of projects coming in politically and with informal requests from many MPs as they cannot formally raise demand in ADP process for their respective constituencies. This creates an apparently 'inclusive' ADP but an unmanageable number of public investment projects.

Second, it failed to fully conceive the goals and targets of Outline Perspective Plan 2010-2021 (OPP) and Sixth Five-Year Plan 2011-2015 (SFYP) and therefore translates into relevant projects as inputs although in theory and on paper it is prepared in line with the government's strategic planning documents, including the OPP and SFYP.

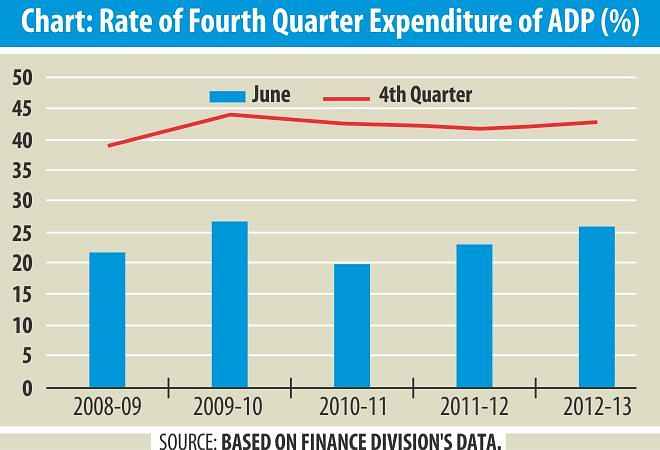

Third, due to annual nature of allocation in line with resource envelope and expenditure targets, there is a rush at the end of every fiscal year, which may be termed as “the fourth quarter syndrome.” For example, more than 40% of ADP was spent in the fourth quarter in the last three fiscal years while about a quarter of ADP was spent only in June alone. Coupled with alleged high prevalence of rent seeking and bribery within the apparatus, it leads to considerable wastage of public resources every year, which would have generated much higher return if they were prepared and implemented as MYPIP.

The idea behind an MYPIP is quite simple. If you feel that you need a house, then you will estimate your resource requirement rather than get incomplete parts of the house with high annual depreciations. After some years you find that there is no house at all but you have already spent hefty sum of money. This is exactly what is happening in ADP despite the fact that the country has set some sensible time-bound targets illustrated in 'Vision 2021.'

Currently, there is dual budgeting emanating from weak linkages between the ADP and MTBF due mainly to insufficient dialogue between the Planning Commission and the Finance Division. Inefficiency in resource allocation and project implementation is also a result of lack of a medium-term perspective in the ADP process. Since there is an absence of sectoral planning within the MTBF, the sector budgets are merely the sum of ministry-level projects that are mainly flagged by the planning wings of the ministries and divisions, and the objectives of the SYFP are only weakly materialised through annual budgets. Surprisingly, there is no qualitative shift in development programming even though we are aiming at becoming a middle-income country by 2021 through double-digit growth. We are still dwelling in the frame set in the early-1970s with 17 sectors.

The MYPIP should be accompanied by adopting Sector Strategy Papers (SSP) to help coordinate between MDAs and deal with intra-sectoral linkages. The SSP can be spectral prioritisation tool guiding to populate the MYPIP. Currently, the SFYP provides limited guidance for effective prioritisation between and within sectors. In addition, line ministries should prepare their medium term strategic business plan (MTSBP) within the purview of SSP for large intra-sectoral linkages. These two should ideally serve as reference frameworks for assessing project proposals instead of the existing programmatic approach resulting in low return.

Such a structural reform in the ADP process is badly needed instead of traditional supplement of new projects, both in green and other pages, thereby leading to insurmountable tasks for the planning and monitoring agencies of the government. Such a change can be initiated only by inserting a paragraph in the upcoming budget speech, although the decision should come from the highest authority of the government. The vision document for an MYPIP can be introduced later on containing the structure, implementation strategy, required changes in the MDAs, and capacity development of the Planning Commission and planning wings of the line ministries.

In addition, it requires a comprehensive document outlining the government's strategic vision, the strategic justification for such a transition, and timing and sequencing accompanied by a precise implementation plan. It will reduce uncertainty over the expected amount of resources and period of multiyear implementation. Besides significantly reducing the large number of small projects and the 'waiting list' approach of the Green Pages, it will be based on a results-oriented resource allocation, which would be introduced through rigorous prior assessment to lower risks and uncertainties related to expected return from large public investment. Second, the public investment would not suffer from low quality due to expenditure spikes in the fourth quarter, as well as in June.

Introducing a meaningful MYPIP crucially depends on close and effective cooperation between the Finance Division and Planning Commission, and there is a need for external support for greater coordination and preparation of Joint Budget Strategy Paper, and the roll out of the SSPs and MTSBPs. It will help ensure greater coordination and synchronisation in preparing the revenue budget and development programme.

The government should also initiate a structural reorganisation of the Planning Commission to establish it as the “core” planning institution. Its role should be redefined to provide strategic guidance to the ministries and formulate indicative plan according to national and sectoral priorities. The government should also strengthen the planning and financial management capacity of its staff through comprehensive formal as well as on-the-job training and capacity building. Also, the capacity of staff within planning wings of line ministries should be strengthened to reduce flow of 'junk' projects from personal influence of the political leaders.

Finally, there is a need for medium-term partnership between planning agencies (Planning Division of MoP and planning cells of LMs) and external stakeholders (think tanks and experts) for transferring skills and technology to strengthen the planning capacity of the government agencies. This would include, but not limited to, sectoral and economy-wide modelling, operations analysis and projections for supporting a meaningful reform of ADP.

The writer is an Economist and Senior Research Fellow, BIISS, Dhaka.

E-mail: [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments