The Daily Star (TDS): What inspired you to begin interviewing people living on the streets?

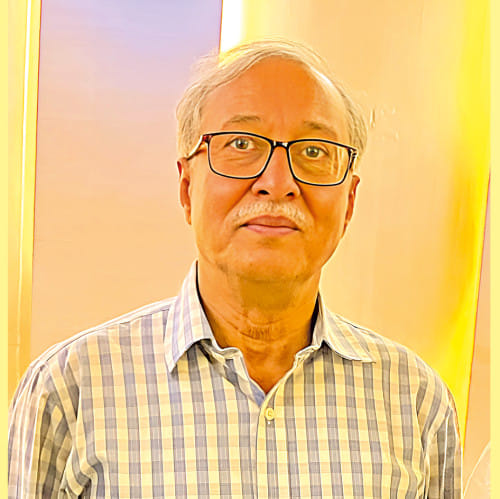

Nasir Ali Mamun (NAM): After the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, I pioneered portrait photography in the country. For over 30 years, I continued this practice, capturing portraits of prominent individuals from various walks of life. Over time, I started to feel that—being born and raised in the capital city—I should also pay attention to what lies beneath my feet, so to speak. I noticed that many small children—boys and girls—were on the streets. I began asking: why are they here? Are they beggars? I started investigating and eventually became involved with Prothom Alo.

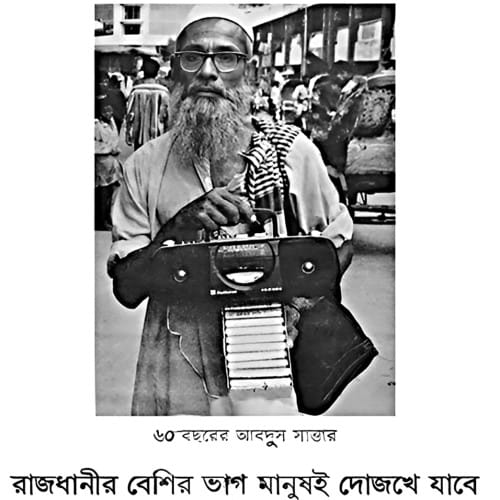

Many of these people were concentrated in areas like markets, Sadarghat, Kamalapur Railway Station, and other locations where people arrived from different parts of Bangladesh. As I continued my inquiry, I realised that these people are not all homeless in the same way. There are two categories: those who live on the streets—sleeping and staying on the roads—and those who live in slums across different parts of Dhaka. The first group begs during the day or wanders around, perhaps hoping for some food or help. Some don't even beg; they just roam. They come from various districts and rural areas of Bangladesh. The main problem they face is poverty. Then there are issues like parental divorce, polygamy, or being separated from their parents at a young age. Many of these children never learn the whereabouts of their parents again, and vice versa. These are the truly homeless.

In contrast, those living in slums are not technically homeless. They have some form of shelter, however informal. But those without an address—they are truly without identity. Every human being has an address. But these people—these children—have neither a visible identity nor an address. In essence, they are the dispossessed, the address-less people. Isn't that astonishing? The government has no statistics on them. No NGO, to my knowledge, has worked specifically with those who are truly homeless. They sleep on the streets, all looking the same—lying down, sitting, roaming.

TDS: What was your interviewing style or technique?

NAM: My main focus had always been on the children, though I did interview a few elderly men and women. But the children were at the heart of it.

I developed a set of seven common questions to identify who was truly homeless and who lived in slums or at least had some form of address. Just by asking those seven questions, I could differentiate between them. I then began conducting interviews using informal language—colloquial speech—transcribing exactly what they said, including their incorrect pronunciations. I noticed that many of the boys and girls, especially girls between the ages of 12 and 14 or 15, would often flee. The boys would too. I used to wonder—why do they run away? I treated them kindly.

Eventually, I discovered that this approach wasn't enough. I stopped carrying bags. I started taking just a small camera, a tiny tape recorder, wore old clothes, and began approaching them more naturally. Then they began to come to me—they felt I was one of them. Many of them said that people like me had come before—chhokra-baj, meaning undercover CID officers. The girls also said things like, "These people talk nonsense—they're bad people." They had already experienced much.

These street children sleep exposed—they have no protection, no homes, nothing. Their bodies, their desires—everything exists in a kind of liminal zone, like a no man's land between two countries. That's where these people truly exist.

And we, as a society, have created this situation. These people—homeless individuals—are not accepted anywhere. We don't give them jobs. Many of us say they are thieves, robbers, or that they will kill us and run away. These are the kinds of narratives that exist about them.

TDS: Was it difficult to publish these stories?

NAM: Normally, no one publishes this kind of writing. First, they said, "Why are you bringing this up? What daily newspaper gives space to these kinds of people?" I said, "Just give it a try—print one." One piece was published. Then, after two and a half months, I requested again and got another published. In the meantime, people like Humayun Ahmed, Latifur Rahman (the patron of Prothom Alo), and Justice Habibur Rahman called up the editor, Matiur Rahman, and praised the writing, saying, "I want to read more." After the third piece, the column continued for almost three years—between 2002 and 2005.

TDS: What was the response to your series?

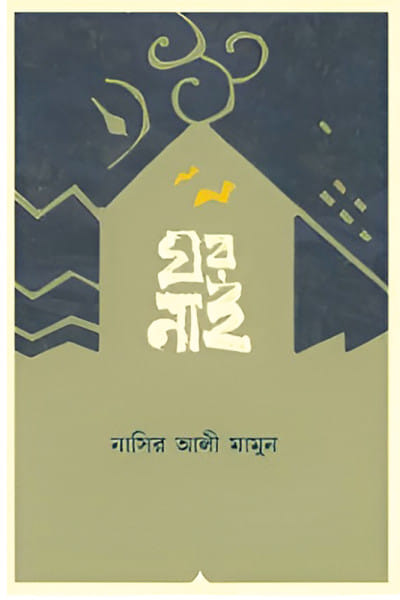

NAM: What surprised me most was the reach of these writings—they were read by everyone, from students in Class Five to elderly readers. The response was overwhelming. Two books eventually emerged from the series. The first, Ghor Nai, was published by Mowla Brothers in 2010. The second, Charalnama, came out in 2016, published by Agamee Prakashani. I co-authored it with poet Shakhawat Tipu.

He was conducting research based on these interviews. His work explores why these people come to Dhaka—what compels them to leave their homes. Within just three to three and a half years of arriving, their native or regional dialects begin to vanish. They adopt Dhaka's hybrid, semi-standard street language. Only those from Chattogram and Noakhali tend to retain their original dialects; the rest lose theirs entirely. This blended Dhaka dialect becomes their new mother tongue.

In effect, a new kind of language is born—a language of the homeless. But it's more than just speech. Through it, we catch glimpses of their psychological landscape, their perceptions of society, and their views of wealth and privilege. These interviews reveal all of that. And why are they so distrustful of us? Because of how we treat them.

When I asked them what a home is like, most couldn't describe it. They would simply say things like, "Room… room… room…" That was the extent of their understanding of 'home'.

TDS: Was there a moment during your interviews that left a lasting emotional impact on you—something you still carry with you today?

NAM: There was a boy named Shahadat. His father came looking for him after his story was published. I asked the man to stay nearby, as the boy was somewhere in Karwan Bazar and not easy to find. A few days later, I came across Shahadat on the street. Even then, he refused to tell me where he was sleeping. Eventually, I found out—he was living on a footpath across the road from Karwan Bazar, under an overbridge.

I asked his father to come with me one night. He arrived, his face wrapped in a gamchha—a poor man, no doubt about it. We began searching for the boy. When I called out to him, Shahadat somehow recognised his father—not from his face, which was mostly covered, but from his clothes, his lungi, his worn shirt, his posture. Only his eyes were visible. And yet, Shahadat knew. He froze.

Then he ran to him.

I said, "Son, don't be afraid. It's your father—no one's going to hurt you."

And then—what I saw in that moment—I've witnessed only once in my life. The two of them embraced tightly, sobbing into each other's arms. It was overwhelming.

Another boy once said something to me that I've never forgotten: "I'll open every lock with the key of my heart." I was stunned. Where had he found such language? He used to sleep on the streets and earn a living repairing locks. I asked him, "You make keys so others can open their doors—but you're so poor, what will you use to unlock your own future?"

He replied, "I'll open it with the key of my heart." Isn't that extraordinary?

The interview was taken by Priyam Paul.

Comments