Chittagong's neighbour Sandwip is absent from Bay of Bengal history because its nature is hard to define. A pirate port in medieval times, its career was different from other pirate-cum-slaving ports because of its many roles: strategic gateway, commercial depot, offensive launch pad, and defensive site. A maritime outlet and transhipment node under local rulers and Arakan, it became a strategic post for the Mughals and a gateway into southeast Bengal for the Portuguese. Ultimately, it telescoped into a slaving hub.

Sandwip's career highlights the many roles played by small places at a time when the world map was not cast in favour of imperial outlets—when an insignificant part of the coast could challenge the expansion of powerful polities.

Another, and more important, reason for Sandwip's absence in history is that it lay outside the national frames through which we view our past. This article will demonstrate how viewing the past through national frames distorts historical understanding.

The Physical Environment

From 1509, ships following the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama had heard of the wealth of Chittagong, which they would call Porto Grande. Luís Vaz de Camões wrote in Os Lusíadas (1572, 10th Canto, Stanza 1):

'The City CATHIGAN would not be wav'd,

The fairest of BENGALA: who can tell

The plenty of this Province? but it's post

(Thou seest) is Eastern, turning the South-Coast.

The Realm of ARRACAN, That of PEGU

Behold, with Monsters first inhabited!'

We tend to equate Chittagong with the delta, but it lies outside it. The delta spans 'Lower Bengal' (samatata) of European records and comprises a terrestrial fringe called bhati that separates the coast from the sea. Emperor Akbar's chronicler Abu'l-Fazl 'Allami claimed that 'the tract of country on the east called Bhati is reckoned a part of this province'. But in another passage, he treated Bangala and Bhati as mutually exclusive; the distinctive feature of the latter was its topography: the word bhāṭi simply means downstream direction. 'Bhati', he said:

"is a low country and has received this name because Bengal is higher. It is nearly 400 kos in length from east to west and about 300 kos from north to south. East of this country are the ocean and the country of Habsha (the Habshis ruled Bengal from 1487 [end of the Ilyas Shahis] to 1493, Husain Shahi accession). West is the hill country where are the houses of the Kahin tribe. South is Tanda. North is also the ocean and the terminations of the hill country of Tibet."

Abu'l-Fazl saw Bengal bound by two oceans. This view likely came from haors and rivers as 'wide and deep as the sea' in popular perception, and it is likely that he was referring to the once mighty but now vanished Karatoya River as the northern ocean.

However, Richard Eaton noted that in Mughal usage of the 16th to early 17th centuries, bhati included the entire delta east of the Bhagirathi-Hugli corridor. Since its western boundary extended from Tanda (part of the 16th-century capital complex of Gaur-Tanda-Firuzabad) down to southwestern Khulna district, the frontier between bhati and Bangala approximated the present frontier between India's West Bengal and Bangladesh.

Bhati

Bhati is how Persian and Bengali sources saw the coast. It is the liminal zone where the land meets the sea, comprising a small part of the delta—the low-lying lands around Dhaka, Tripura, Mymensingh, and Sylhet, forming a triangle surrounded by the Ganga, Brahmaputra, and Meghna river systems.

Sandwip lies at the Meghna estuary's centre, between 22º16' and 22º43' north latitude and 91º23' and 91º40' east longitude. To its north is Chittagong and mainland Bangladesh; to its south, the Bay of Bengal; to its east, the Sandwip Channel; and to its west, the Hatia Channel. The Meghna network links it to Tibet, northern Burma, and Yunnan through the Brahmaputra. This was once a major communication route, and the medieval port of Samandar of the Arab mariners and Muslim merchants was probably on this route.

Despite its accessibility, Sandwip's environment is vulnerable. Hydromorphological processes have influenced the formation of this funnel-shaped coastal area, and the Meghna estuary is subject to cyclones and tidal surges from the Sandwip and Hatia Channels. We estimate that the Noakhali–Chittagong coast has a 40% plus frequency of cyclones compared to other parts of the coast (ranging from 16% to 27%). Sandwip lies in this most cyclone-prone area. This factor, and the fact that rivers in Bengal are notorious for changing course almost overnight, meant that few attempted to control this harsh land. The hostile environment also ensured that there are few vestiges left of the Portuguese presence in Sandwip.

Backstory

Like its environment, Sandwip's borders were hostile and contested by Bengal, Tripura, and Arakan—a powerful state to its east. Environment recognises no frontiers. Stephan van Galen remarks that Arakan–southeast Bengal form an environmental continuum; both have a climate and geography quite different from the Ganga and Irrawaddy plains. Both share a very high level of rainfall (reaching, on average, 500 cm per year), which makes for higher rice yields—contrasting with the much drier Ganga and Irrawaddy plains. Although the steep and rugged Arakan Yoma makes overland travel difficult, intersecting rivers and shallow coastal waters between the two polities provide a good infrastructure for trade and communication.

In 1406, Ava (upland Burma) attacked Arakan, and its king fled to Bengal. After staying there for several years during Ghiyas ud-Din Azam Shah's reign (1390–1411), he regained his throne with Sultan Jalal ud-Din's help in 1430. Known as Narameikhla (also Suleiman Shah, 1404–34), he founded the city of Mrauk U and initiated mint reforms using trained personnel and technology sent from Bengal. But relations soured as Arakan claimed dwadas Bangla (the 12 lands of deltaic Bengal ruled by the baro bhuinya) as areas of Arakanese influence. These lands had been alienated to Bengal in return for help in regaining the throne. In pursuit of these claims, Arakan raided Bengal throughout the seventeenth century. These raids can be read as assertions of a past territorial grandeur.

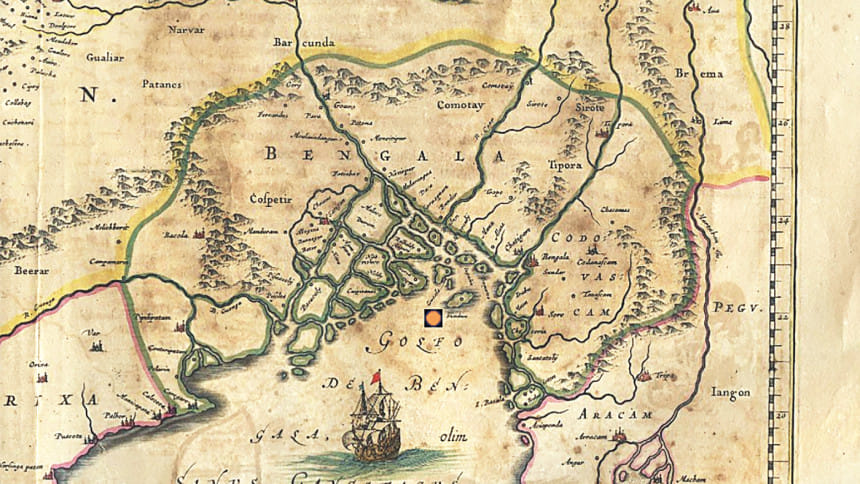

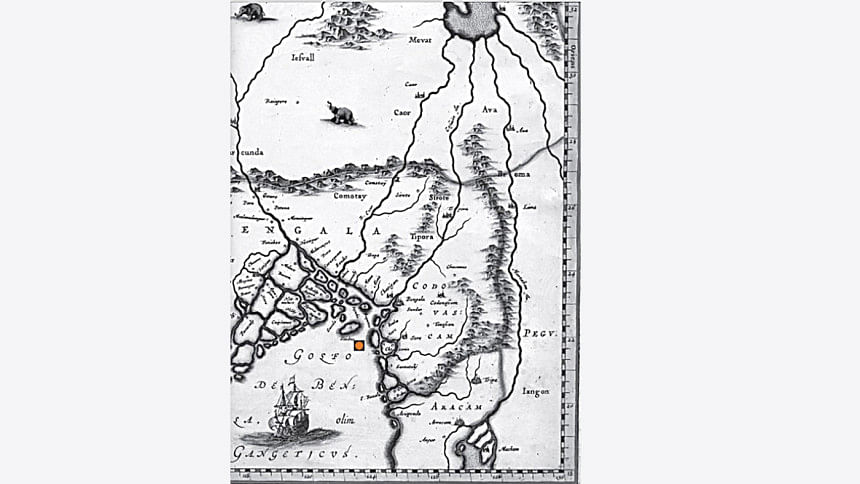

In 1538, Sher Shah defeated the Husain Shahis, and then, in 1576, the Mughals defeated the Afghans. But the delta's rulers, the baro bhuinya, governed independently. Two rulers—from Sripur and the 'Island' or 'Kingdom' of Chandecan (a chief called Chand Khan; see images 1 and 2)—claimed Sandwip's revenues. Arakan would contest these claims.

Locating Sandwip

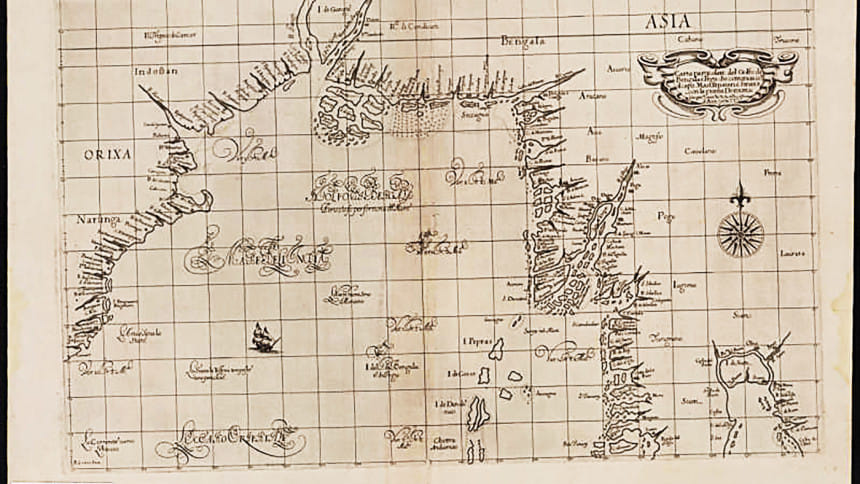

Sandwip Upazila in Chattogram district was 'Sundiva' in European texts and maps. Located on the Bengal–Pegu route, it is marked in de Barros' Map of Bengal (Quarta Decadas da Asia, Lavanha edition, 1615), shown but not named in Gastaldi's 1561 Map of Asia, and also in Linschoten's 1596 map. Dutch and French cartographers marked it until 1747: Johann and Cornelius Blaeu (1638, image 3); Johannes Jansson (1639 and later editions in the 1640s and 1650s); Nicholas Visscher (1660, 1670); Nicholas Defer (ca. 1685); Nicolas Sanson d'Abbeville (1705/1720); Jacques-Nicolas Bellin (1747).

Sandwip was important, but its hostile physical and political surroundings would prevent it from carving out a prominent place in Bay of Bengal history.

Adjacent to Arakan but held by outsiders, Sandwip's history is difficult to recover, as it lay in a disputed frontier area. We are not sure which power held the area at the start of the 16th century. It was probably Tripura, for in 1516 Husain Shah seized Chittagong from Tripura. But by 1537, Bengal's politics had become turbulent, the Portuguese controlled the seaboard from Orissa to Chittagong, and in the absence of a central authority, 'trade coins' minted at Chittagong passed as legal tender. In the early 17th century, the Mughals conquered southeast Bengal, the delta's rulers were defeated, and Bengal was made a Mughal province. This anarchic half-century benefitted Arakan.

Travellers have left behind accounts of the region. Niccolò de' Conti passed this way in 1421–22, but since he does not mention Sandwip, we assume its rise postdates his visit. Clearly a char that appeared later, Sandwip is not mentioned in the 1521 Portuguese account of Bengal either. But this account saw the area as highly urbanised, with market towns succeeding each other at small intervals: Aluia, Jugdia, Gacala, Meamgar, Noamaluco—the last name clearly testifying to a land newly risen from the sea, a char now habitable and taxed (image 4). The same account notes that despite being a fertile land producing rice, sugar cane, and black and white textiles sold in its numerous shops, and a land experiencing great riverine and maritime traffic, it showed startling contrasts—swampy one moment and full of clear lakes the next. The area was heavily infested with pirates. Some islands were empty.

Was Sandwip one such island? Is this why it has left so few traces?

Sandwip appears on the historical stage in 1569. That year, on his way back from Pegu, a cyclone caused Cesare Federici's ship to be shipwrecked at Sandwip. Staying for 40 days, he found it a pleasant place, well run by a Muslim governor. He states:

"I went aboard the ship of Bengala, at which time it was the yeere of oftentimes, there are not stormes as in other Countries; but every ten or twelve yeeres there are such tempests and stormes, that it is a thing incredible, but to those that have seene it, neither doe they know certainly what yeere they will come… In this yeere it was our chance to bee at Sea with the like storme… this Touffon or cruel storme endured three days and three nights: in which time it carried, away our sayles, yards, and rudder… this Touffon being ended, wee discovered an I[s]land not farre from us, and we went from the ship on the sands to see what I[s]land it was: and wee found it a place inhabited, and, to my judgement the fertilest I[s]land in all the world, the which is devided into two parts by a channell which passeth betweene it, and with great trouble wee brought our ship into the same channell, which parteth the I[s]land at flowing water, and there we determined to stay fortie dayes to refresh us. And when the people of the I[s]land saw the ship, and that we were comming a land: presently they made a place of Bazar or Market, with Shops right over against the ship with all manner of provision of victuals to eate, which they brought downe in great abundance, and sold it so good cheape, that wee were amazed at the cheapnesse thereof. I bought many salted Kine there, for the provision of the ship, for halfe a Larine a piece, which Larine may be twelve shillings sixe pence, being very good and fatte; and foure wilde Hogges ready dressed for a Larine; great fat Hennes for a Bizze a piece, which is at the most a Penie: and the people told us that we were deceived the haife of our money, because we bought things so deare. Also a sacke of fine Rice for a thing of nothing, and consequently all other things for humaine sustenance were there in such abundance, that it is a thing incredible but to them that have seene it. This I[s]land is called Sondiva belonging to the Kingdome of Bengala, distant one hundred and twentie miles from Chitigan, to which place we were bound."

With a diverse economy, Sandwip served as a refitting station for riverine traffic, and produced rice, grain, poultry, and cottons. Alexander Hamilton (ca. 1688–ca. 1733) remarked:

"Sundiva is an Island four Leagues distant from the rest, and so far it lies in the Sea… it may serve to shelter small Ships from the raging Seas."

A rupee spent at Sandwip yielded 580 lbs of rice, or eight geese, or 60 poultry. It also exported 200 boatloads of salt each year.

Sandwip's First Phase

Sandwip's turbulent politics began in 1590. In that year, the Chittagong Portuguese under Antonio de Souza Godinho fought Min Nala, Arakan's new governor at Chittagong, captured the fort, and forced Sandwip to come under their Chittagong establishment. But the island was a no-man's-land, with Portuguese authority in force only in some places. Sripur's Kedar Rai asserted overlordship and claimed its revenues. This unclear status would haunt Sandwip. Although a renewed purpose to conquer the southeast is seen in General Man Singh's choice of Dhaka as a base from 1602, Mughal presence was nominal. They were defeated in 1602, and Domingos Carvalho, one of Kedar's officers, re-conquered Sandwip. Kedar claimed he had 'liberated' Sandwip from the Mughals.

But the locals now rebelled against the Portuguese. Carvalho asked the Chittagong and Dianga Portuguese for help. Manuel de Matos, leader of the Dianga Portuguese, led 400 men in Carvalho's support. Since both together defeated Sandwip, each took a half to govern, and it seems Kedar still maintained his overlordship.

Min Razagyi, Arakan's king, fearful of being trapped between the Portuguese strongholds in Chittagong, Dianga, and Sandwip, sent a force of 150 jalias, "in which were some catures and other great ships, with many falcões and cameletes." Surprisingly, Kedar allied with Min Razagyi and sent 100 cosses (light boats suitable for fighting on rivers, not at sea) against Sandwip. The Portuguese won this battle in 1602. In retaliation, Arakan harassed Jesuit and Dominican missionaries. Jesuit Father Francisco Fernandes was stripped, blinded, shackled, and thrown into prison, where he died on 14 November 1602. Four Jesuit fathers, led by Father Brasio Nunes, left their church in Sandwip and moved to Bengal.

Carvalho offered Sandwip to the King. The Estado da Índia's viceroy at Goa agreed, hoping that Carvalho and Matos would bring the Bengal-based Portuguese back into the Estado's service. As the conquest of Sandwip was now official, and Portugal accepted it as a crown possession, the King presented Matos and Carvalho with the Order of Christ and made them nobles — Fidalgos da Casa Real.

But Sandwip's political status was still contested. Arakan attacked it in 1603. Then, Pratapaditya of Chandecan, a powerful ruler who was seeking to expand in the delta, entered the scene. He beheaded Carvalho and sent the head to Mrauk U. This ended the Carvalho phase — the first Portuguese phase of Sandwip's history. Only Manuel de Matos was left to rule over Sandwip.

Meanwhile, de Brito — whose star was rising under Min Razagyi — planned a takeover of the entire coast from Sandwip to Syriam. This would be the second phase of Sandwip's history, and it would continue to shape Portuguese commercial strategy in the northern Bay of Bengal.

Rila Mukherjee is a historian and the author of India in the Indian Ocean World (Springer, 2022).

Comments