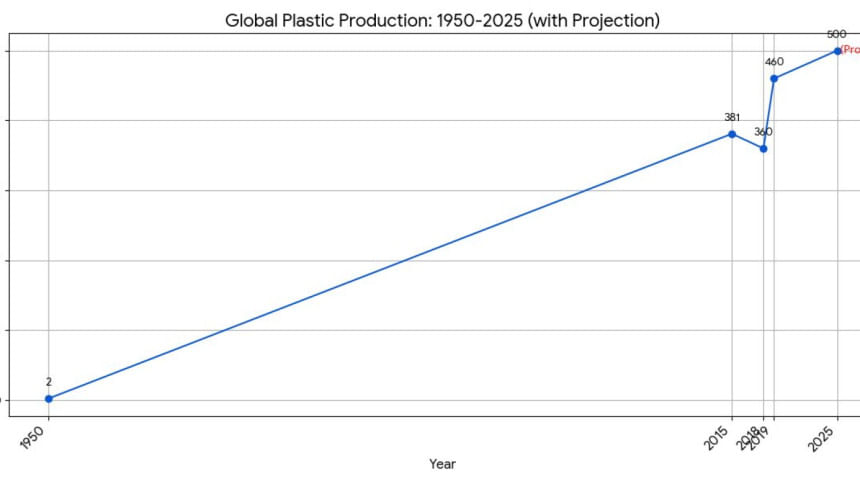

Plastic pollution, projected to cause US$4.5 trillion in global economic damage by 2040, poses a severe threat to human health and ecosystems. In Bangladesh, per capita plastic use has tripled since 2005, with mismanagement affecting both urban and rural communities. The UN Environment Programme estimates 19–23 million tonnes of plastic waste enter aquatic ecosystems annually, exposing humans to polymers, microplastics, and nanoplastics, and causing widespread deaths of wild and aquatic species. In March 2022, at UNEA-5.2, governments agreed to create a legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, later named the Global Plastic Treaty. Negotiations are currently under way in Geneva to finalise its adoption.

Mehedi Hasan, Coordinator of Payra Planet Praxis – a Bangladeshi organisation dedicated to tackling the triple planetary crises of climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss – spoke with Dr Patrick Schröder, a circular economy expert and Senior Research Fellow at Chatham House who is closely involved in the Treaty negotiation process, to explore its background, latest developments, and implications for Bangladesh and countries facing similar challenges.

Mehedi Hasan (MH): Let's start with the Global Plastic Treaty. What is the background of this Treaty, how will it be finalised, and what does it mean in tackling the global plastic crisis?

Patrick Schröder (PS): At the fifth session of the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-5.2) in 2022, a resolution was adopted by all governments to start negotiations on a legally binding instrument to tackle plastic pollution. The resolution highlights the full lifecycle of plastics, which also includes upstream production [initial stages of the plastic lifecycle, primarily focused on production of plastic polymers (pellets) from these resources]. An Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was then formed. There have been five negotiations already, the last one in Busan (INC-5.1). The mandate initially sought to complete the negotiations within two years. However, in Busan, countries did not reach an agreement, so the negotiations were extended. INC-5.2 started in Geneva on August 5 and will end on August 14, 2025. Hopefully, this will be the last round of negotiations, after which the legally binding instrument will be adopted.

There is a strong desire by many of the parties to complete this. UNEP wants to finalise it as well. But there are obviously still many hurdles. Countries disagree on various aspects. There are many issues still to be addressed, including whether the Treaty should contain a production target, such as capping production at 2020 levels. There are also outstanding questions around finance. Various articles in the current negotiation document are in brackets, which means they are still open for negotiations. For example, Article 3 concerns plastic products and whether there should be a list included – a blacklist of products to be phased out or banned by countries.

Many of the technical details can still be worked out further down the track. As in the climate negotiations, many of the technical issues can be addressed later. So the key question is around political will and the willingness to compromise.

MH: What will be the potential implications of the Treaty for countries like Bangladesh? And how can this Treaty ensure environmental justice and effectively prevent waste colonialism?

PS: Specifically regarding Bangladesh, I do not know if it currently imports plastic waste from other countries. I know there are several countries doing this. Malaysia, for example, has imported a lot of plastic waste over the years, with consequences for local communities. Malaysia has now vowed to completely ban imports of plastic waste. The Treaty itself would not address such imports, because plastic waste shipments are already regulated by the Basel Convention. So the Treaty would not duplicate this and will reaffirm the provisions that already exist under Basel.

That is one aspect. The other aspect is about how the Treaty can support developing countries to tackle the pollution crisis. This is relevant not only for Bangladesh but for many other countries that do not produce much plastic or any at all. There need to be various mechanisms, much of which comes down to the financial mechanism, to support direct investments in waste management and collection infrastructure, as well as investments in recycling infrastructure. Under the Treaty, these investments need to come from both public and private sources, and these details still need to be worked out.

MH: How will these investments happen? From where will the funds come?

PS: Investments could come, for example, through multilateral development banks like the IFC, the World Bank, or the European Investment Bank. In addition, there could be bilateral cooperation. Organisations such as GIZ and other development implementation agencies will increase their projects related to plastic. We are already seeing such an increase.

That will be one part, but there will also be a need for policies that generate resources from the private sector. Companies that produce plastics will need to contribute to waste management and the management of plastics.

MH: Bangladesh shares many rivers with India and Myanmar. Do you believe this Treaty can effectively tackle transboundary plastic flows through these rivers?

PS: At this moment, I do not think it will specifically cover that. To tackle it, the source countries need to take better measures to prevent the leakage of plastics into the rivers. The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) has proposed some additions to the existing text that relate to transboundary flows. They have proposed text on remediation, essentially to address existing damage caused by plastic pollution, including if it is caused by external actors. I would suggest that if the remediation text is adopted as an additional article within the Treaty, it could potentially also apply to the situation you have described.

MH: What role can civil society organisations and local communities play, along with the government, in implementing the Global Plastic Treaty?

PS: Civil society organisations, local communities, municipal governments, local businesses – everybody has a role to play in implementing the Treaty. The Treaty is there to set the framework and to get governments to commit to taking action. It will also enable closer coordination between countries. There will be support, but on the ground it will ultimately depend on every individual citizen. Collection only works, or waste segregation only works, if citizens participate. Civil society organisations already working on plastics will hopefully also receive additional support. I think more philanthropic organisations will provide resources towards this, including from the corporate sector.

MH: Now we would like to hear from you about Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). Bangladesh's Environment Adviser announced in January this year that EPR Guidelines are in the making. So, what is EPR? How can it control plastic pollution?

PS: EPR is a tool to generate additional revenues from producers or importers to cover the cost of collection, waste management, and recycling. Depending on the volumes of plastics that organisations put onto the market in the country, they will be charged a certain fee. That fee is normally managed by a Producer Responsibility Organisation (PRO), an independent body that also manages the data and the fee payments. There are different ways in which EPRs can be structured: they can be either voluntary or mandatory. However, voluntary EPRs have not been very successful, and most EPRs are mandatory. One of the important functions that EPR can also play is through 'eco-modulation': a policy mechanism to encourage companies to shift to more sustainable products. For example, EPRs can require a minimum recycled content for products and achieve this by lowering the fee. If a company has 30% recycled content in its products, it pays a lower fee compared to other companies that do not have recycled content. This is a way to stimulate more sustainable design and circularity.

MH: What are the opportunities and challenges you anticipate in implementing EPR effectively in Bangladesh?

PS: It is good to study how other countries have designed and implemented EPR for plastic, and the experiences from India and South-East Asian countries will be useful. It should not be replicated in a copy-paste fashion. It is particularly important to look at what has not worked. For example, the EPR guidelines published by the Indian Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) in 2022 have not been fully implemented and there are multiple challenges, including getting large manufacturers and producers to register and disclose details about plastic production volumes.

MH: Considering Bangladesh's unique socio-economic context, do you believe EPR is an effective solution for tackling plastic pollution?

PS: Yes, EPR is suitable for Bangladesh, but it needs to be designed and implemented in a way that fits the current socio-economic context. There are different EPR models that can be used, and EPR systems can evolve over time. As EPR systems are complex, a phased approach will be necessary. Setting the scope of the system is the first step. Setting the right targets will also be crucial. One can start with basic fees in the beginning, then move to introducing eco-modulation fees once the system becomes more mature. Eco-modulation fees are important to encourage and reward producers that design better products with increased recycled content.

MH: A common challenge in identifying the producer's responsibility arises when companies utilise third-party producers for plastic packaging. How can EPR address this issue and enforce responsibility in such complex supply chains?

PS: EPR systems are based on the policy principle of holding industry stakeholders, such as producers, accountable for the entire lifecycle of their products, particularly for the take-back, recycling, and final disposal. Beyond the upstream producers of plastic nurdles (the "raw materials" for plastic products and packaging), there are different categories of industry stakeholders that need to be included. For example, manufacturers of plastic packaging, importers of plastic products, and the consumer-facing brands that use plastic packaging for their products, as well as retailers who sell plastic products – all these different stakeholders need to be included. Another group of stakeholders that need to be included are recyclers.

MH: Large plastic producers in Bangladesh hold significant political influence. How can EPR ensure their accountability?

PS: This is indeed one of the main challenges of EPR systems – they require significant institutional capacity within the ministry and related government agencies involved in the design and implementation of EPR. What will be important for Bangladesh is to ensure mandatory registration of all industry actors (including those that are powerful and might want to resist regulation) and accurate disclosure of how much plastic packaging is introduced to the market. Mandatory EPR systems are more effective than voluntary approaches.

MH: A significant portion of Bangladesh's plastic producers are very small businesses that do not have licences. How can EPR regulate these informal businesses, ensuring a just transition?

PS: That is not only the case in Bangladesh; in many other countries, small businesses make up the majority of operators in the plastics sector. This can be addressed through a phased approach in allocating responsibility to different industry stakeholders. For example, small businesses should be required to register with the EPR system and provide the required information, but they can initially be exempt from the EPR requirements and fees. The EPR should also set a specific threshold for compliance, e.g. the annual turnover of a company or the volumes of plastics the company produces. This would then determine which companies need to comply.

MH: What lessons can Bangladesh learn from other developing countries that have successfully implemented EPR, especially for overcoming initial resistance?

PS: The development of the plastic EPR system in Bangladesh and the institutional capacity for its effective implementation should be supported by countries that already have good experiences with EPR. This includes not only European countries, but also Korea and Japan. It is a suitable area for technical cooperation and capacity building, but it also requires funding to set up new structures within the Bangladesh Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. In my opinion, it is an excellent opportunity to use international development cooperation and specialised agencies like UNIDO. For example, the EU-funded SWITCH to Circular Value Chains Programme, implemented by UNIDO in Bangladesh to support circularity in the textile and RMG sector, could be expanded to include EPR policy support.

For further inquiries, Dr Patrick Schröder can be reached at [email protected], and Mehedi Hasan can be reached at [email protected].

Comments