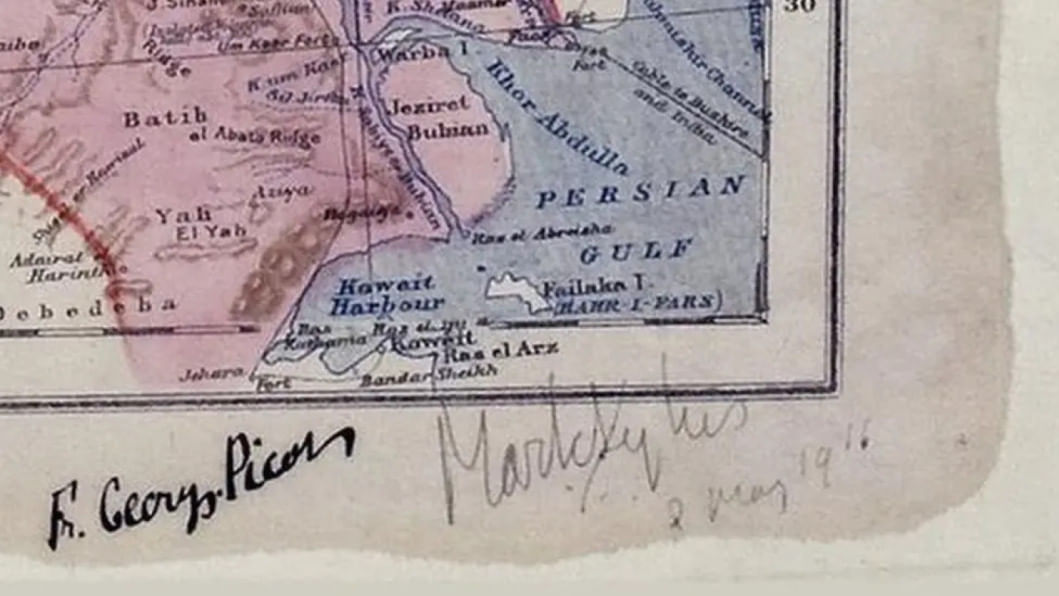

In the annals of modern Middle Eastern history, few documents have cast a longer or darker shadow than the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. These so-called "lines in the sand," arbitrarily drawn by British diplomat Mark Sykes and French diplomat François Georges-Picot, came to symbolise the legacies of imperial cartography—an era in which European powers apportioned territories with scant regard for the people who lived there. The Agreement, a clandestine understanding between Britain and France (with Czarist Russia's acquiescence), foreshadowed the end of Ottoman suzerainty in the Arab world and the emergence of Western hegemony in the Middle East. On paper, it was merely a wartime contingency plan—an imperial map drawn with a ruler across the Levant. But in practice, it birthed a legacy of disillusionment, resistance, and postcolonial fragmentation that still reverberates across the Arab world and beyond.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement was not only a geopolitical manoeuvre—it was a paradigmatic expression of imperial cartography, embodying the colonial logic of spatial domination and epistemic erasure. The Arabs were not consulted in the redrawing of their lands; their futures were rendered negotiable, exchanged like commodities between European powers under the veil of civilisational uplift.

What makes Sykes-Picot so symbolically enduring is precisely its duplicity: it functioned not only as a betrayal of political promises but also as a deeper metaphysical violence—the colonial production of space and identity, overwriting local sovereignties with imported constructs and imposed inflections.

Postcolonial scholars such as Edward Said have long underscored how imperialism was not just about the accumulation of territory but the control of knowledge, language, and representation. Sykes-Picot operated through this dual register. On the one hand, it imposed artificial borders that undermined communal, linguistic, and tribal continuities. On the other, it enabled a Eurocentric narrative of rational governance and modern statecraft, casting colonial rule as an ordering principle in the wake of Ottoman "decay." In this sense, the agreement exemplified what Gayatri Spivak later identified as the "epistemic violence" of colonialism—a systemic erasure of indigenous modes of knowing and being.

The redrawing of boundaries under Sykes-Picot disregarded the deeply enmeshed histories of the peoples of the region. Cities such as Aleppo, Mosul, and Jerusalem were not merely strategic outposts—they were cosmopolitan hubs where multiple ethnicities, languages, and faiths coexisted in complex, if at times tense, social fabrics. The European division of the region into arbitrary national units fractured these relations, embedding sectarian divisions into the very scaffolding of the state. The modern crises of Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine cannot be fully understood without reference to this colonial genealogy. Indeed, the fragmentation of the Levant into incompatible nation-states prefigured the persistent failure of postcolonial governance structures, most of which remain tethered to the logic of their colonial inheritance.

But we must go further. The Sykes-Picot Agreement was not a historical aberration; it was a symptom of a broader epistemological project—what Achille Mbembe calls the "commandement" of colonial rule. This concept refers to the multifaceted ways in which colonial powers instituted authority, extending beyond coercion into the symbolic and psychological realms. The very idea that European powers could draw lines on maps and engineer nation-states according to strategic convenience reflects a form of colonial sovereignty that presumed native populations to be objects rather than subjects of history—an outlook that necessitates a radical recalibration of historiography to account for silenced voices and indigenous political imaginaries. However, the persistence of this logic today, often under the guise of humanitarian intervention or developmental aid, signals how colonial modalities are reconfigured rather than resolved in the postcolonial present.

In Palestine, the ongoing settler-colonial reality underscores the unfinished business of Sykes-Picot. While the 1917 Balfour Declaration—issued by Britain and expressing support for a "Jewish national home" in Palestine—followed soon after Sykes-Picot, the two are interlinked in their shared disregard for the rights and aspirations of indigenous Arab populations.

It is no accident that many contemporary insurgent movements in the Middle East invoke Sykes-Picot as a point of origin for the region's misfortunes. ISIS, for instance, made a spectacle of symbolically bulldozing the border between Iraq and Syria, declaring the end of the "Sykes-Picot regime." While such gestures are politically opportunistic, they underscore a critical truth: the colonial cartographies of the early 20th century continue to shape imaginaries, grievances, and resistances in the 21st. This is not to suggest a simple causal line from Sykes-Picot to contemporary conflicts, but to recognise how colonial partitions created structural conditions for enduring instability. When postcolonial states are born not from popular will but imperial design, legitimacy becomes fragile and social cohesion elusive.

Moreover, the "secret" nature of the agreement speaks volumes about the colonial disposition. It was premised on duplicity—promising Arabs independence while secretly conspiring to deny it. This imperial practice of double-speak is not a relic. Contemporary foreign policy in the region continues to operate through backdoor arrangements, covert operations, and selective alliances. Whether in the manipulation of proxy regimes, the instrumentalisation of sectarian identities, or the conditionalities imposed through IMF restructuring programmes, the Middle East remains a laboratory for neocolonial experimentation. The ghosts of Sykes-Picot have not been exorcised; they have simply changed form.

Postcolonial critique must also address how these colonial legacies are internalised and perpetuated by local elites. Many post-independence regimes in the Middle East adopted the centralised, extractive, and securitised model of the colonial state, using nationalism to mask the absence of popular participation. In this context, the critique of Sykes-Picot must go beyond external blame to interrogate how colonial structures are reproduced internally through authoritarianism, corruption, and the suppression of dissent. Here, Partha Chatterjee's distinction between the "thematic" and the "practical" state becomes useful: while nationalist movements often envisioned a decolonised future, the practical postcolonial state largely inherited the colonial state's infrastructure and logic.

What makes Sykes-Picot so symbolically enduring is precisely its duplicity: it functioned not only as a betrayal of political promises but also as a deeper metaphysical violence—the colonial production of space and identity, overwriting local sovereignties with imported constructs and imposed inflections.

In Palestine, the ongoing settler-colonial reality underscores the unfinished business of Sykes-Picot. While the 1917 Balfour Declaration—issued by Britain and expressing support for a "Jewish national home" in Palestine—followed soon after Sykes-Picot, the two are interlinked in their shared disregard for the rights and aspirations of indigenous Arab populations. The creation of Israel in 1948, and the dispossession of Palestinians that accompanied it, can be viewed as a continuation of the colonial denial of Arab sovereignty. The region's enduring statelessness, refugee crises, and cycles of violence are thus not anomalies but the aftershocks of a deeply flawed imperial project.

The current calls for redrawing Middle Eastern borders—whether along ethnic, sectarian, or geopolitical lines—echo the original violence of Sykes-Picot. But such proposals fail to confront the foundational problem: that political legitimacy and sovereignty in the region were never allowed to emerge organically. To merely replace one set of externally imposed boundaries with another is to repeat the error. Instead, what is needed is a decolonial rethinking of space, community, and governance—one that resists the tyranny of the colonial map and instead centres the lived realities and political aspirations of the region's peoples.

In conclusion, the Sykes-Picot Agreement remains more than a historical footnote. It is a synecdoche of colonial betrayal, a cartographic violence that haunts the present. To "peek" into it is to glimpse the mechanics of empire—how power operates through maps, language, and false promises. But it is also an invitation: to challenge the postcolonial condition not as an inevitable legacy, but as a structure that can be interrogated, dismantled, and reimagined. For as long as the lines drawn in 1916 continue to dictate the fate of millions, the work of postcolonial critique must remain unfinished.

Faridul Alam writes from New York City

Comments