In his analysis of the Estado da Índia, which was the official name of the Portuguese Empire, George Winius distinguished between the formal administration by the Estado's headquarters at Goa over overseas possessions and the 'informal empire', which he called the 'shadow empire', that the Portuguese established in the Bay of Bengal. The shadow empire was a unique experiment carried out by sailors, merchant adventurers, pirates, and missionaries, with little formal sanction either from Goa or from Portugal.

The general perception of this informal/shadow empire is that it was formed of renegades. But Sanjay Subrahmanyam saw many of the 'minor' settlements of the informal empire as commercially very dynamic. The informal empire was surprisingly successful in extending trade from the Bay of Bengal to Melaka, Macau, and beyond. The careers of Domingos Carvalho and Manuel de Matos, which we have already outlined, that of Filipe de Brito de Nicote, the subject of this article, and the career of Sebastião Gonçalves y Tibau, which we will examine later, show that these settlements lay somewhere in between 'formal/informal' and 'major/minor'. Sandwip's distinctive position as a minor, disputed island sheds new light on Portuguese 'informal' expansion in the northern Bay of Bengal.

Genesis of the Informal Empire

During the viceroyalty of Lope Soares de Albergaria (1515–18), private Portuguese interests paralleled official attention to the Bay. Men were allowed to leave official employment to seek their fortunes and conduct activities far from the reach of the Estado. Many thus left the Arabian Sea region, where Goa was situated and which was the area of official Portuguese activity, and went over to the Bay of Bengal region. Over time, others followed the same path after completing their service to the Portuguese crown, preferring to become rebels in relation to Portuguese authorities, or to settle in Asian territories rather than return to Portugal.

Bengal was one such territory, with bands of Portuguese men and communities of Luso-Indians born of unions with local women. Estimates from the end of the 16th and the middle of the 17th century suggest the presence of between 2,000 and 3,000 such people—merchants, pirates, and mercenaries in the service of local rulers. Jan Huygen van Linschoten saw these people as living "in a manner like wild men, and untamed horses, for that every man doth there what hee will, and every man is Lord," i.e., they were not subject to any law or political power. Portuguese words like almari, istri, ispat, chabi, balti, botam, janala, perek, alpin, toalia, etc., entered the Bengali vocabulary at this time.

However, many of these renegade Portuguese maintained contact with official Portuguese representatives, and they had the possibility of reintegrating into Portuguese society through pardons granted by the Portuguese authorities. Distinguishing oneself in a trading or political capacity was a sure-fire path to a pardon. At the beginning of the 17th century, the Bengal-based Portuguese supplied information and services that were crucial for territorial conquest. This reveals the importance of communication channels that were maintained between the official and non-official realms. In 1602, Domingos Carvalho and Manuel de Matos tried to take advantage of this factor in their conquest of Sandwip. Situated close to Chittagong, this island was ideally located to attack the city and permit entry into southeast Bengal.

The Coastal Dynamic

At the centre of the Meghna estuary, Sandwip lay in a harsh and unforgiving land. Bengal's rivers are notorious for changing course almost overnight; this ensured that few had succeeded in controlling this hostile land. But this demanding coast, patterned by creeks and inlets through which rivers emptied into the sea, was a positive factor in Portuguese expansion. Other than the local rulers, the unofficial Portuguese, designated feringi, were the first to try to patrol this land's many waterways. Their informal empire was based on small islands and chars (sandbanks) in the marshy delta, with river channels providing the main means of communication. The many inlets and quick exit points through labyrinthine channels served as relay stations and stopovers to support plundering campaigns and provide supplies, as well as to permit ambushes.

The Portuguese operated with local support from bases in southeast Bengal, often as pirates but also hoping to participate in the local trade, including the slave trade. They benefited not only from the existence of the fluvial communication network, but also from an abundance of wood, which encouraged boat building. They profited from the numerous islands in the region, and tried at times to become de facto rulers of small, uninhabited but strategically located islands. The distinctive topography thus dictated sailing patterns which were largely coastal in nature.

Bengal's dense fluvial network, resembling a high-tension spider's web, therefore saw intense navigation facilitating contact between the coast and the interior. Because the northern Bay was subject to vicious cyclones, river ports with sheltered harbours were the norm, rather than open sea ports. Such a location meant a robust, effective, and durable relationship with the hinterland. River ports could not be held separately from the political powers based in the interior. Some amount of negotiation with political authorities over the coast was inevitable. This would lead to friction, as we shall see.

Despite lying in the most cyclone-prone area of Bangladesh, the growing Bay trade from the end of the 16th century—especially the salt trade—made Sandwip's maritime outlet an attractive trans-shipment hub for all. Even when the trade telescoped back into a coastal network, in 1838 some 500,000 maunds of salt were imported into the Dhaka region from Bhalwa, Sandwip, and Chittagong in no fewer than 160 sloops. Maghs and Chinese from Arakan's southeast coast engaged in this trade.

Sandwip's Growing Importance

Despite lying in the most cyclone-prone area of Bangladesh, the growing Bay trade from the end of the 16th century—especially the salt trade—made Sandwip's maritime outlet an attractive trans-shipment hub for all. Even when the trade telescoped back into a coastal network, in 1838 some 500,000 maunds of salt were imported into the Dhaka region from Bhalwa, Sandwip, and Chittagong in no fewer than 160 sloops. Maghs (ethnic Arakanese) and Chinese from Arakan's southeast coast engaged in this trade.

More than Chittagong, Sandwip was commercially important to Portugal at the end of the 16th century. Chittagong was frequently under Arakan's control, but Dianga—Chittagong's neighbouring port—was a notorious slave port with a small Portuguese settlement.

Portuguese-held Sandwip, functioning as a rival entrepôt (which Arakan destroyed only in 1617), was a key reason for Chittagong's slow development under Arakanese administration.

Historian Michael Charney identified Sandwip's commercial potential and strategic location as obstructing Chittagong's trade at this time, thereby making Sandwip significant to both Portugal and Arakan. Jesuit chronicler Fernão Guerreiro estimated that, at the beginning of the 17th century, Sandwip had 60 Portuguese trading ships, compared to 30 at Mrauk U—the inland port-capital of Arakan—and just ten at Chittagong.

What was the significance of Sandwip to Portugal at a time when its expansion in the Bay was faltering? In Philip's orders to the adventurer Filipe de Brito de Nicote dated 23 January 1607, Sandwip's importance to the Portuguese was clearly underlined: "And because the conquest of Pegu and the island of Sundiva has the importance that you know, I charge you dearly with doing for them everything in your power..." Also, the king needed funds to finance Portuguese expansion. Chittagong's treasure—which he referenced in a letter dated 20 February 1610—was considered worth taking.

De Brito's career illustrates the different roles that Dianga and Sandwip played in Portuguese designs: Dianga was a slave and pirate port, while Sandwip, under de Brito, was to be part of a grand scheme of official Estado expansion in the Bay, with Syriam as the centre and chief port.

However, in 1607, the Portuguese were driven out of Dianga, the most important settlement after Chittagong. To stem the decline, Philip II sought to end the casual nature of Portuguese settlements along the Bay. In a letter dated 26 March 1608, he stated his purpose: "…and how I considered it convenient to grant jurisdiction to Filippe de Brito, its captain [of Syriam], to reduce to my obedience the Portuguese that are in Bengal."

We have covered the first phase of Sandwip's unique history from 1590 until 1603; let us now examine its second phase.

Sandwip 1603–07: Pivot between Lisbon, Syriam, Mrauk U

The career of de Brito (Image 1) shows that Philip II of Portugal was contemplating an end to the informal empire in the Bay. De Brito, in service under Arakan's Min Razagyi from 1599, had by 1602 carved out a state for himself in the area stretching from the east of Chittagong, through a portion of Arakan, into Syriam (now known as Thanlyin), Lower Pegu, and Martaban. This made him an enemy of Arakan.

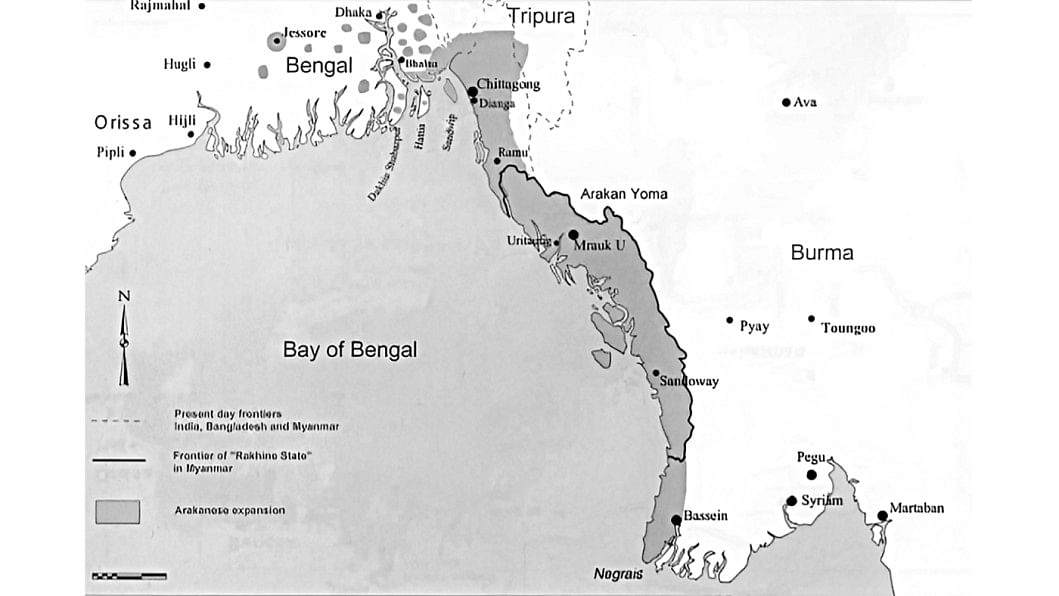

In 1602, Viceroy Saldanha married his niece to de Brito and appointed him commander of Syriam and general of the campaign for conquering Pegu. De Brito subsequently received the crown of Pegu 'in the name of the King of Spain and Portugal'. Sandwip, by virtue of its location, became crucial to de Brito's plans for expansion. Image 2 shows the places linked with de Brito's small empire and their proximity to Chittagong–Sandwip.

The Lower Burma ports traded with ports such as Sandwip via the coastal route. This route is shown in Image 3, which is a modern rendering of the coast as it was circa 1630. Because cyclones wreaked havoc on this coast, a safe haven like Sandwip was necessary.

Of a storm on the Burma coast in 1566–67, the Italian traveller Cesare Federici wrote:

'Wherefore in this Shippe we departed in the night, without making any provision of our water: and wee were in that Shippe fowr [four] hundreth and odde men: wee Departed from thence with Intention to goe to an I[s]land to take in water, but the windes were so contrary, that they woulde not suffer us to fetch it, so that by this meanes wee were two and forty Dayes in the Sea as it were lost, and we were driven too and fro…'.

De Brito was promised jurisdiction over Bengal in return for his undertaking to bring the Portuguese renegades living there back into the service of the Estado. In a letter to the king of Portugal, he suggested that he should seize control of southeast Bengal and build a fort at Chittagong, which would allow him to bring the Portuguese desperados under Goa's control. He became busy not only defending the new Portuguese possessions against neighbouring princes with force and diplomacy, but also in planning to expand the Portuguese empire in the Bay. His project envisaged making Syriam the main port of call in Burma, and Sandwip a subsidiary port to supplement Syriam's activities.

He insisted to the king of Portugal that Syriam be well fortified and provided with men and ships, with which he could force all navigation between India and Melaka to stop at Syriam and pass through the Custom House there, bringing huge benefits to the Portuguese treasury. To this effect, he requested the king to issue necessary orders to Portuguese merchants to call at Syriam; the rest of the ships he would force with the fleet at his disposal. He also patrolled the Bay to stop smuggling and thereby enrich his (and Portugal's) coffers.

To de Brito, the possession of a Portuguese enclave in the Bay was necessary for the Estado, not only because the monsoon system made it very convenient for shipping, but also because such a site was full of commercial advantages. But these plans were difficult to implement, and in 1605 de Brito faced a joint Arakan–Toungoo (Burmese) campaign to recapture Syriam. The campaign failed, but the wars against Arakan were taking their toll. Whether he could bring southeast Bengal under his control remained doubtful. In 1607, Arakan's Min Razagyi attacked Syriam again, but the siege was inconclusive and left de Brito still in control.

But his grand schemes ultimately failed. The Portuguese king eventually did not support de Brito's plans for the takeover of Sandwip. Nor did the Viceroy at Goa. De Brito never ruled over Sandwip.

Tragically, de Brito never received the support of Lisbon during his lifetime. Orders were sent by the king on 15 March 1613 for all Portuguese ships trading in the Bay to stop at Syriam and pay taxes, but by the time the letter reached, the Burmese had killed de Brito in Syriam.

Historian Michael Charney identified Sandwip's commercial potential and strategic location as obstructing Chittagong's trade at this time, thereby making Sandwip significant to both Portugal and Arakan. Jesuit chronicler Fernão Guerreiro estimated that, at the beginning of the 17th century, Sandwip had 60 Portuguese trading ships, compared to 30 at Mrauk U—the inland port-capital of Arakan—and just ten at Chittagong.

Sandwip Abandoned

De Brito and his schemes were not universally welcomed, and his plans for expansion into Bengal were challenged by the Portuguese at Dianga. In 1607, they advised the Arakan king against handing over Sandwip to him. Although the Dianga Portuguese were chased out by Arakan that same year, this complicated the plans for the Estado's acquisition of Sandwip. Manuel de Matos, sometime administrator of half of Sandwip's revenues and leader of the Dianga Portuguese, died at Dianga in 1607 when Arakan attacked the settlement. Fateh Khan, a Muslim officer of Pero Gomes—to whom Matos had entrusted Sandwip in his absence—now decided to take control of the island.

Gomes appears to have been a very poor administrator, since the king refers to him as a 'vile man of less substance than that of the conquistadores'. He told the Viceroy of India, Dom Francisco d'Almeida, that he should consider administering Sandwip directly if Matos continued to leave Gomes in a position of authority.

Usurping power from the unpopular Gomes, Fateh Khan had all 30 Portuguese traders on Sandwip, as well as their families, killed. All of the native Christians and their wives and children were also killed. Fateh Khan then raised a garrison of 'Moors' and Pathans and created his own fleet of 40 ships, which he maintained with the revenue from the prosperous island.

Fateh Khan felt he had a mission, and he displayed it prominently on his flag: 'Fateh Khan, by the grace of God, Lord of Sandwip, shedder of Christian blood and destroyer of the Portuguese nation'. In the same year, Min Razagyi made a pact with the Dutch to hand over Sandwip to them. Affairs at Sandwip were now in chaos. At this point entered Sebastião Gonçalves Tibau, a salt trader who had come to Sandwip. Sandwip now became the site for the career of this extraordinary adventurer—but one with far less talent than de Brito. This would form the third and final phase of Sandwip's unique history.

Rila Mukherjee is a historian and the author of India in the Indian Ocean World (Springer, 2022).

Comments