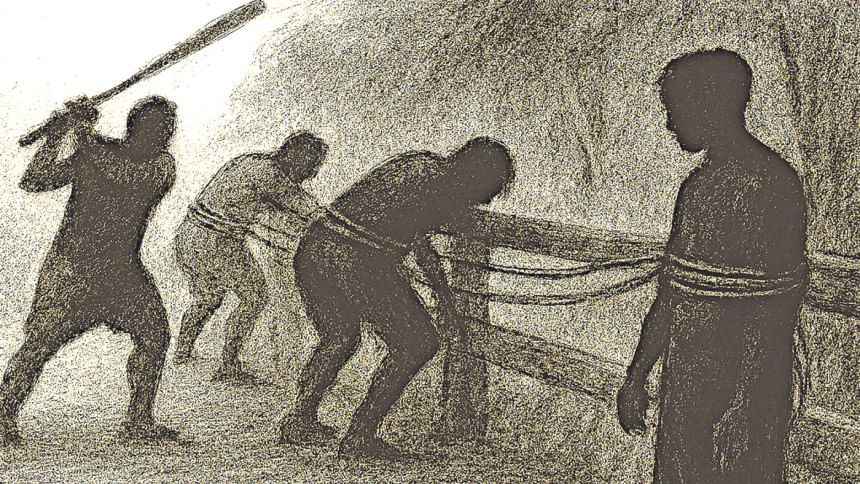

When justice is hijacked by rage and rumour, it takes only minutes for a mob to become a murderer. Like those two men beaten to death in Sirajganj on August 4 over alleged cattle theft. Or the Hindu homes vandalised in Rangpur in July, triggered by a Facebook post. Or the lynching in Cumilla's Muradnagar claiming the lives of a woman and her two children earlier that month. Or the 70-year-old barber and his son brutally attacked following accusations of hurting religious sentiments in Lalmonirhat in June. The man in Bhola whose eyes were gouged out by a mob in March. The Uber driver, mistaken for a mugger, beaten to death in Dhaka that same month. Or the mentally unstable Tofazzal killed for suspected theft in a university dorm last September.

Each of these incidents is a chilling reminder of how mob violence is carving deep, brutal scars into the fabric of Bangladesh — fuelled by rumours, sharpened by rage, and amplified by social media. In this digital era, where smartphones are ubiquitous and digital freedom runs largely unchecked, misinformation is becoming a deadly weapon, and the consequences are playing out in real time.

The orchestration of violence

According to Shahzada M Akram, Senior Research Fellow at TIB, the anatomy of a mob in Bangladesh often follows a grim pattern. While some outbreaks are purely driven by misinformation, circulated through social media or messaging apps, others are far more calculated.

"There are instances where misinformation is deliberately seeded to serve political or personal motives," he explained. "Religious sentiment becomes an easy trigger." In cases like Dinajpur, mobs have vandalised temples and shrines based on false claims, while incidents like the Cumilla Muradnagar beating show how local interest groups exploit digital rumours to incite violence. Often, law enforcement arrives too late to prevent the damage and, by then, the mob has already done its work.

Nur Khan Liton, a prominent human rights activist, pointed out that while mob beatings existed in the past, their nature has evolved drastically in recent years. "In earlier times, there were isolated incidents, sometimes planned, but what we see now is a coordinated culture of violence," he explained.

These orchestrated mobs not only physically attack individuals; they target homes, properties, and even legal processes. "There have been instances where defendants in custody, brought before the courts, were assaulted. In some cases, mobs attacked the accused even when they were taken to the hospital for treatment," observed Liton.

These events often involve politically motivated small groups seeking personal or ideological gain. "They don't necessarily have formal political party structures, but they fish in troubled waters, exploiting chaos for their own interest," he mentioned. "Such actors sometimes even co-opt law enforcement to facilitate attacks, further blurring the lines of accountability."

The implication is clear: mob violence in Bangladesh is not merely spontaneous public outrage. While emotions play a role, many incidents are carefully orchestrated to destabilise communities, exploit religious or ethnic sentiments, and intimidate political and other social groups.

Mobs, often ideologically motivated, consume these viral narratives and interpret them through personal or political lenses. This ideological lens, combined with low digital literacy, creates fertile ground for rapid escalation from online outrage to street-level attacks.

Misinformation and the digital echo chamber

In the midst of this orchestrated violence, social media has become the accelerant. Dr Md Khorshed Alam, Associate Professor in Mass Communication & Journalism at Dhaka University, highlighted the structural changes in media dissemination. "Traditional media like newspapers, TV, and radio had gatekeeping systems. Information passed through checks, and accountability was embedded," he explained. "Social media, however, allows consumers to become producers, or prosumers, with little or no gatekeeping."

This shift has enabled rapid, often unchecked, circulation of misinformation, disinformation, and mal-information. Even mainstream media, when publishing online, has tended to prioritise speed and virality over accuracy, sometimes adding sensational elements to attract likes, shares, and comments. Dr Alam noted that this "viralism" replaces careful journalism with a race to capture attention, often without verifying facts from all parties involved or considering potential consequences.

When such content circulates, it can catalyse real-world violence. Mobs, often ideologically motivated, consume these viral narratives and interpret them through personal or political lenses. This ideological lens, combined with low digital literacy, creates fertile ground for rapid escalation from online outrage to street-level attacks. "People see an excerpt, a photocard, or a video clip, and make decisions without context. Even if a correction is issued later, the initial impact is far more powerful," explained Dr Alam.

A digital chain reaction

Neither misinformation nor mob violence are new phenomena. But what social media has done is intensify the chain reaction. A crime occurs, a video circulates online, and public outrage follows. What was once a local issue now reverberates across the country in minutes.

This repeated exposure to crime through visual content online can provoke a sense of collective anger. "When a crime happens, and its visual representation is out on social media, general people can get disproportionately enraged," mentioned Qadaruddin Shishir, Fact Check Editor at AFP.

This effect is intensified in a society where visible justice is slow or absent, and the public may perceive taking matters into their own hands as the only option, resulting in mob justice, often brutal and tragically misdirected.

Md Rezaul Karim Shohag, a lecturer in Dhaka University's Criminology Department, reinforced this point with insights from routine activities theory. The theory suggests that crime occurs when a likely offender encounters a suitable target in the absence of legal guardianship, emphasising factors such as availability, proximity, and exposure that influence crime rates.

"In many recent mob cases, those involved are often the likely offenders. When perpetrators go unpunished, groups with personal grievances see an opportunity and join in the violence," he explained.

The role of impunity

The growing public participation in mob violence stems from a breakdown in accountability. When justice remains elusive and offenders walk free, ordinary citizens, who would normally fear the law, start to shed that fear, emboldened by the impunity they witness.

"The general people in the mob don't wake up every day intending to commit crimes. But when they see perpetrators repeatedly go unpunished, their fear of the law disappears. They start to believe they too can cross the line and walk away," said Shishir from AFP.

In such an environment, one misleading image or miscaptioned video can ignite rage. Sometimes even outdated photos, like those claiming attacks on BNP offices, are recirculated to stir political outrage and potentially violent responses.

Current weaknesses within the law enforcement amid the volatile political climate have reinforced this sense of impunity among people. Many officials fail to intervene, while others are complicit or sidelined. The result is a culture where mob beatings have become normalised. "People are adjusting to crimes without punishment, and this lack of deterrence only encourages further violence," added Shohag.

The criminology expert also pointed out the deterrence theory, where ensuring the severity of punishment matters more than who committed the crime. "From last August to this August, many people have been beaten or killed by mobs, yet how many have actually received justice? If proper justice had been served even for just ten people — that alone could have deterred others and set an example. We are neither deterring crime nor creating such examples, which only encourages more people to join mob violence," he said.

The proliferation of monetised content has created a dangerous incentive system. The more outrageous the post, the higher the click count.

Political manipulation and ideological triggers

"Recent cases of mob violence have been serving political ends. Small groups without formal party structures use social unrest to advance agendas, intimidate minorities, and destabilise society," said human rights activist, Liton. These orchestrators exploit emotional triggers, such as religious sentiment or perceived injustices, while simultaneously avoiding legal consequences.

Dr Alam echoed this, noting that ideological baggage among social media users intensifies mob activity. Users interpret viral content according to pre-existing beliefs. Photocard journalism, circulating excerpts, images, and snippets without context, further fuels the cycle, according to him.

When lies go viral

What makes this crisis especially dangerous is the speed of viral content. "By the time fact-checkers verify something, the damage is often done," mentioned Apon Das, a researcher on information integrity at Tech Global Institute. The Facebook algorithm, like others, promotes content that generates high engagement, meaning sensational and fear-inducing posts travel faster than the truth.

Fact-checking efforts, while crucial, often fall short. "Fact-checkers don't have the same reach as viral posts," added Das. This gap is not just technical, it is deeply educational. Media and digital literacy remain worryingly low among Bangladesh's general population. "Most people don't know how to verify the content they consume, or even feel the need to."

Minhaj Aman, co-founder of Activate Rights also draws attention to the algorithmic influence. "Social media platforms show you more of what you already believe. This creates an echo chamber," he explained. When users consume one fake news item, the algorithm begins to serve more of the same, reinforcing their biases and skewing their perception of reality.

Online editions of newspapers often fail to replicate the rigorous verification applied in print. Reproductions of partially verified news, coupled with low treatment of corrections or rejoinders, further confuse the public. When clarifications are issued, they rarely receive the prominence of the initial story, leading to entrenched misconceptions that can trigger violence.

Disinformation as income

There is also another dimension to this: financial and reputational incentives. Many actors knowingly spread disinformation for money, political leverage, or sheer visibility. "For some, social media isn't just a platform; it's an income source. Outrage and sensationalism are profitable," Das explained. The proliferation of monetised content has created a dangerous incentive system. The more outrageous the post, the higher the click count.

Yet Bangladesh lacks clear legal definitions and investigative mechanisms to address such targeted disinformation. While cyber laws exist, they often fall short — or worse, get misused. "The laws are vague about intentional misinformation and can be used to silence critics rather than penalise actual bad actors," Das warned.

Media must do better

Media institutions, both traditional and digital, have a critical role in the current situation. Shishir argued that mainstream media's editorial decisions can either inflame or calm volatile situations. Clickbait headlines and fear-inducing narratives amplify mob action. Dr Alam highlighted that online editions of newspapers often fail to replicate the rigorous verification applied in print. Reproductions of partially verified news, coupled with low treatment of corrections or rejoinders, further confuse the public. When clarifications are issued, they rarely receive the prominence of the initial story, leading to entrenched misconceptions that can trigger violence.

Education and digital literacy

Literacy, both general and digital, is crucial in curbing the spread of misinformation and mob violence. Dr Alam noted, "The internet, smartphones, and social media are accessible to everyone, but understanding varies widely. Those with lower comprehension are more easily influenced." Apon Das and Aman advocated for national campaigns to increase media literacy, ideally integrated into school curricula, community workshops, and online platforms. Citizens must learn not only how to recognise fake news but also how to respond responsibly. Waiting before reacting to viral content, cross-checking information, and understanding context are essential steps.

Shishir added that unrestricted internet access without education is a recipe for misuse. Countries like Indonesia introduce media literacy early in education, a model Bangladesh could emulate. Digital literacy empowers citizens to resist misinformation and reduces the potential for collective violence.

Strengthening fact-checking and regulatory capacity

Currently, fewer than 30 active fact-checkers operate in Bangladesh, a stark mismatch for a population exceeding 50 million internet users. Aman emphasised the need for alliances between media, fact-checkers, and civil society, similar to India's Shakti coalition, to counter false narratives effectively, especially before the election.

Dr Alam underscored the necessity of updating cybersecurity and digital security laws, ensuring that legal enforcement mechanisms can detect and respond to misinformation. He also suggested government negotiations with social media platforms to minimise the spread of harmful content, following international examples such as the way the EU fined Google for abusing its monopoly.

The delicate balance

Experts agree that solutions cannot rely solely on legal mechanisms. Capacity building — within the state, media, and civil society — rather than simple control is more crucial. Strengthening accountability, empowering fact-checkers, and enhancing digital literacy collectively form a sustainable approach.

Bangladesh stands at a crossroads between digital freedom and digital peril. Without decisive action the cycle of mob violence is likely to continue. Knowledge, vigilance, and democratic accountability remain the only antidotes to a society where rumours and rage can so easily override justice.

Miftahul Jannat is a journalist at The Daily Star.

Comments