In conversation with Mou Banerjee, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and author of The Disinherited: The Politics of Christian Conversion in Colonial India, published by Harvard University Press (2025).

The Daily Star (TDS): Christianity had early encounters with the Indian subcontinent through Jesuit missionaries, long before the British conquest of Bengal in 1757. How did missionary activities evolve under Company rule up to 1857, and what significant transformations occurred after the Great Revolt? Did you observe notable differences between Catholic and Protestant missionary approaches within the colonial framework?

Mou Banerjee (MB): While Europe experienced an age of evangelical awakening in the eighteenth century, political circumstances in India posed challenges to the work of missionary preaching. The great evangelical revival was widespread in English society and cut across the barriers of class. Even if the British government did not officially approve of evangelism and conversion in the new Indian Empire, in reality almost all British administrators in India held strong evangelical beliefs and sympathised with missionary activity. Evangelical missions expressed publicly what many British administrators felt privately—that saving the souls of their Indian subjects was an important part of the imperial project.

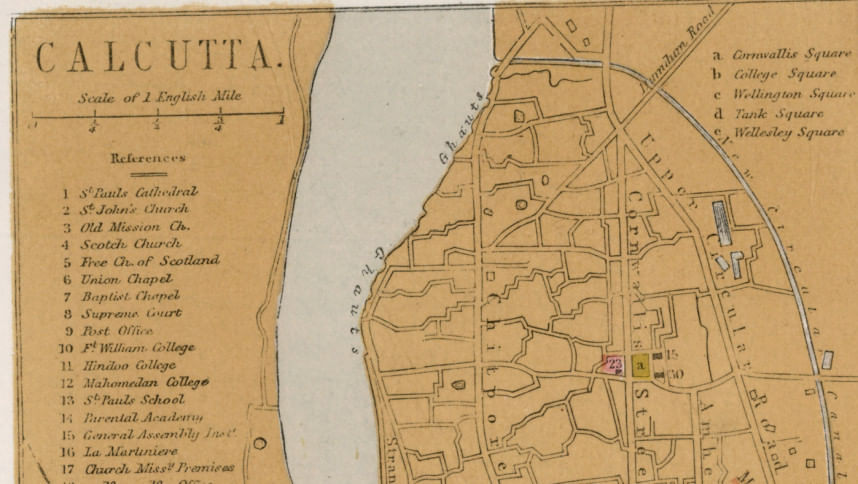

Until 1813, when their presence on British domains was ratified legally during the renewal of the East India Company's charter, missionaries had to carry out their evangelical activities in Bengal from bases in neighbouring colonial holdings of other European powers, such as the Dutch, the French, and the Danish. The Baptist Mission operated out of Serampore, the Danish settlement, which was situated upriver from Calcutta. Established by the shoemaker and autodidact William Carey in 1798, the Serampore Baptist Mission in many ways provided the blueprint for modern Protestant missionary activity in British India. The missions established a strong presence and secured patronage by inextricably entwining themselves with unofficial and semi-official services provided to the East India Company's administration. Missionaries, men and women, enjoyed free mobility within the British colony as linguists, ethnographers, preceptors, doctors, and nurses, among other occupations.

Apologetic disputations were characteristic of the ways in which Indians reacted to evangelical proselytism. These intellectual (and sometimes physical) conflicts began in the first decade of the nineteenth century, with Raja Rammohan Roy's apologetic entanglements with the Serampore Baptists on Christian theology, Christian ethics, and Hindu philosophy. From the Serampore Baptists to Alexander Duff of the Scottish Free Church in the 1830s, down to the celebrated controversy between Bankimchandra Chatterjee and William Hastie in the 1880s, Protestant Christian missionaries were convinced that the moral and material progress of Bengal, and of India more broadly, depended on the spread and success of the evangelical mission—and on the conversion of Indians to Christianity.

They were constantly stymied, however, by the conditions of colonial rule and the sustained opposition of Indian intellectuals to Christian evangelism. First, the British administration's professed public stance was one of non-interference in the religious practices of Indians, and they were careful not to upset the religious sensibilities of their fractious subjects. This non-interference policy was reiterated several times between 1781 and 1858. Second, these apologetic debates, instead of establishing the supremacy of Christianity as the missionaries wanted, would go on to shape the history of marginalisation of minorities in India and incite a pattern of terrible violence—social, political, and legal—in both colonial and postcolonial India.

The history of Christian conversion in Bengal shows that the boundaries of religio-political identities in India began to meaningfully cohere at least forty years prior to the Mutiny of 1857—and in direct response to Protestant evangelism. In India, the emergence and sharpening of political consciousness based on religious identity began as early as the second decade of the nineteenth century. The events of 1857 were a watershed in terms of the evangelical civilising mission in India. They demonstrated the long-standing and profound anxiety that Indians felt about forced mass conversions, which has periodically bred paranoia and resulted in political violence in South Asia.

The spectre of Christian evangelism haunted many Bengali intellectuals. While elite Bengalis were justly proud of their own moral and material progress under British rule and often identified with the high-minded rhetoric of enlightenment and liberalism in India, this enlightened liberalism also entwined with suspicion and even hatred towards religious minorities, exemplified by Bankimchandra's attitude towards Christianity and Christian converts (and towards Muslims, more famously).

The threat that Christian conversion, real or imagined, posed to Hindu and Muslim Indians had an outsized and profoundly transformational effect. Their anxiety far exceeded the statistical significance of conversions, given that the number of Christians in the Indian census data remained steady at a mere 1–1.5 percent across the nineteenth century, and this is true of Bengal as well. In this sense, Bengal suffered from a conversion panic more than a conversion crisis. But these anxieties did powerful political and intellectual work, laying the groundwork for Christianity to emerge as an oppositional and threatening "Other" to both Hinduism and Islam.

An older and more pervasive Catholic influence had prevailed in Southern India since at least the fifteenth century. The historiography on Christianity in India is largely centred on the latter region, which had the largest population of native converts and is still home to the largest portion of India's native Christians, although there is a rapidly expanding Christian population in India's north-eastern states.

However, the case in Southern India—and to an extent, the Punjab—is quite different from the case in Bengal for a number of reasons. First and foremost, Southern India is characterised by a much longer history of Christian conversion than Bengal. While Thomas the Doubter supposedly landed in India in AD 52 and immediately converted aristocratic communities who then identified themselves as Nazarene or Syrian Christians, Catholic evangelism and the conversion project in Southern India began in earnest with the arrival of Vasco da Gama in 1498 and the beginning of the Portuguese Padroado.

From the beginning, Catholic missionaries in Southern India also oversaw mass conversions of entire communities—often artisanal, lower-caste, and non-elite. This approach, along with the entrenched presence of the Church in the region, meant that conversion had a very different impact on existing socio-economic and political structures than it did in Bengal. The Catholic Church was also far more accommodating of syncretic practices and often tacitly allowed Hindu and Muslim caste and kinship hierarchies to remain undisturbed when communities as a whole converted to Christianity.

Community conversions even enabled upward socio-political mobility among Southern India's convert groups in a way that was impossible for converts in Bengal. From the late eighteenth century, missionary activity in Southern India occurred primarily in the princely states, where the centre of power was an Indian prince. In many cases, princes directly employed missionaries in their administrations and worked closely with them in ways that were not possible in domains under direct British rule, like Bengal. In these princely kingdoms, the relationship between the missionaries, the administration, and the native communities was marked by a different set of manoeuvres and contestations than in those regions, like Bengal, that were at the centre of British power in India. The situation in directly administered Indian territories was vastly different politically.

TDS: In your book, you discussed the significant debate between William Hastie and Bankimchandra Chatterjee during the Dowager Maharani's śrāddha ceremony. Could you elaborate on the core issues that divided Christian missionaries from the conservative and liberal Bengali Hindu intelligentsia on the question of conversion? How did these debates influence the evolution of anti-colonial sentiment in Bengal and across India?

MB: The debate between Hastie and Bankimchandra that you refer to was superficially about the ostentatious celebration of the śrāddha or last rites of the wife of a scion of the famous Sovabazar Raj family. The Sovabazar family, as you know, had been founded by Nabakrishna Dev, Lord Clive's munshi and co-conspirator at Palashi (Plassey). Anyway, this family became the centre of orthodox Hindu factionalism in the nineteenth century, during the lifetime of the redoubtable Raja Radhakanta Dev, who was the de facto arbiter of Hindu religiosity, or Hinduani, during this period.

The Dev family and the Dharma Sabha played an important role in the 1840s and 1850s, aiding the concerted effort led by Debendranath Tagore of Jorasanko in combating the pernicious effects of "missionaryism"—the conversions of minor schoolboys in Bengal by their missionary preceptors. The Devs used their status as the leaders of the conservative faction of Calcutta's elite to consolidate public opprobrium against British missionaries and their pedagogical activities during the controversies surrounding Gyanendramohan Tagore's conversion in 1851 as well.

Calcutta's Christian missionaries, irrespective of their affiliations, were understandably not enamoured of the Devs and their socio-religious performances, which were aimed at upholding exactly those values in Hindu society that were seen as the most regressive and superstitious by evangelical missions. Thus, the occasion of the Dowager Maharani's śrāddha was an opportunity for retaliation by the missionaries. The śrāddha gave rise to a vicious epistolary battle between the missionaries and the Bengali intelligentsia, represented by Rev. William Hastie on one hand and the pioneering Bengali novelist and political theologist Bankimchandra Chatterjee on the other. This apologetic debate was a bitter battle to define what Hinduism meant to believers in Bengal and to decide how far ritualistic performances shaped the contours of its popular practice. It is not surprising that Bankimchandra Chatterjee's war of words with Hastie began with what he saw as the irascible missionary's misunderstanding and misrepresentation of private practices of Hindu piety. He rightly criticised Hastie for his lack of tact and tastefulness in criticising the śrāddha, which was ostensibly a private act, even though it was celebrated on a grand public scale by the Devs.

However, the occasion clearly pointed to the deeply held religious convictions of even progressive Indian men. There was a coexistence of their rational, modern, educated public personas and their deeply pious and observant private selves, without any seeming contradictions between these two positions. For Hastie, this seemingly paradoxical coexistence of Western "rationality" and "Eastern" superstition was embodied in the overt idolatrous practices of the Devs of Sovabazar and legitimised by the respectful obeisance paid to idol worship by even the most liberal among the Bengali intelligentsia. To Hastie, this was an unbearable hypocrisy that needed to be challenged. His assessment, closely following the template of apologetic debates between missionaries and Indians for a century, was in many ways the final such attempt at a theological critique of Indian faith systems in Bengal.

The Bankim–Hastie debate occurred at the noon of imperial glory, at the moment when Victorian belief in the untrammelled progress of science and capitalism, undergirded by a strong Protestant ethos, held sway over half the world. Therefore, Hastie personified the mystification that most British commentators experienced in confronting the staunch idolatry of Indian Hindus. Hastie's chief critique of Hindu Bengali leaders was that they had all received the benefits of English pedagogy; had nurtured close social ties to the British establishment through their participation in the commercial, political, and administrative services; and had enjoyed close ties of friendship with British civilians. And yet, in their private lives, they refused to turn away from the "superstitions" of the Hindu faith.

In accusing the most progressive Bengali men of letters of religious hypocrisy, Hastie was also making a more troubling point. If these Indian men still held on to their ancestral beliefs, even after more than a century of colonial pedagogical, social, and political influence, it showed that they, and Bengalis in general, could never be civilised by European norms. In other words, Indians, even of the most elite socio-economic class, still needed to bide their time in the "waiting room of History" before they could be seen as social, racial, and political equals of the British and therefore considered capable of ruling India by themselves.

Given the historical context, it became necessary for intellectuals like Bankimchandra to consider Christianity seriously on its own terms—as a religion but more importantly as a denominator of racial and social difference for Hindu Indians who engaged with it. Bankimchandra accused Hastie and other missionaries of wilful ignorance of the tenets of Hindu religious philosophy and the cultural practices of Hindu piety. The Bankim–Hastie debate was, in many ways, a first step in Bankimchandra Chatterjee's conception of a Hindu political theology, an "uncompromising avowal of faith in Hinduism." Bankimchandra's influential anti-Muslim rhetoric would eventually be accepted as an indispensable component of Indian nationalism in the late nineteenth century.

TDS: Your analysis of the Great Tagore Will Case reveals how the Anglo-Indian legal system dealt with the inheritance rights of Christian converts. Could you elaborate on how such legal disputes reflected broader colonial anxieties about religious conversion? Beyond the legal domain, how did Christian conversions impact land ownership and property relations in colonial Bengal?

MB: One of the consequences of converting to Christianity, young Bengali boys in the nineteenth century would soon realise, was disinheritance—at the most obvious level, they lost any rights to their patrimony. But implicated in the loss was also any social or moral capital that might have been their birthright as a result of familial and communitarian networks, which would have provided both security and access to support that was lost irretrievably as a result of their conversions. Conversion began to slowly mean an inheritance of violent loss and unmooring, not merely for low-caste or poorer converts but also for hitherto socially and economically privileged high-caste converts. Their missionary preceptors began to lobby the British administration to rectify what they saw as a terrible wrong being perpetrated against their enlightened students and deterring others from conversion. The grieving parents, who had lost their children and faced loss of face and ostracism in their communities as a result of their child's actions, began to use the Anglo-Indian legal system to ensure that converts would not inherit any of their ancestral or patrimonial possessions.

We see this exemplified in the Great Tagore Will Case. The contest over inheritance central to the case was the result of a highly public fallout between two of the most influential members of a colonial Bengali aristocratic elite family: Babu Prosonnocoomar Tagore or Thakur (1801–1868) and his only son and heir Gyanendramohan (1826–1890). Prosonnocoomar, who had duelled in print with Krishnamohan Banerjee, Bengal's most well-known Christian convert, in the 1830s, had by the early 1840s risen to become an eminent legal scholar and lawyer—and in 1854 the first Indian member of the governor-general's Legislative Council. Under the guidance of his father's old nemesis Krishnamohan Banerjee, Gyanendramohan converted to Christianity in 1851 and married Krishnamohan's daughter amid enormous public scandal.

In response, Prosonnocoomar disinherited his son and willed his ancestral properties to his nephew, Maharaja Jatindramohan Tagore, instead. Gyanendramohan contested his father's will in a legal case that would come to be known as the Great Tagore Will Case. Moving from the civil court in Calcutta to the Privy Council in London, where it was finally resolved in 1872, the case involved properties valued at hundreds of thousands of pounds sterling.

Since the early 1800s, the Anglo-Indian legal system had been adapting to the peculiar circumstances of colonial rule, further complicated by the existence of innumerable local customary laws and practices. British lawmakers favoured the dharmashastras and especially the Manusmriti—thereby mistranslating a commentary on social morals and their legal applications into a code of positive Hindu law. The facts of the Great Tagore Will Case proceeded from the complications that surrounded inheritance in India after the passage of the controversial Lex Loci Act in 1850. This law confirmed that converts to Christianity in India could not be disinherited by their fathers from ancestral and paternal property.

TDS: Could you shed light on how Christian missionary efforts were received by Bengali Muslims—particularly in terms of social, economic, and theological responses?

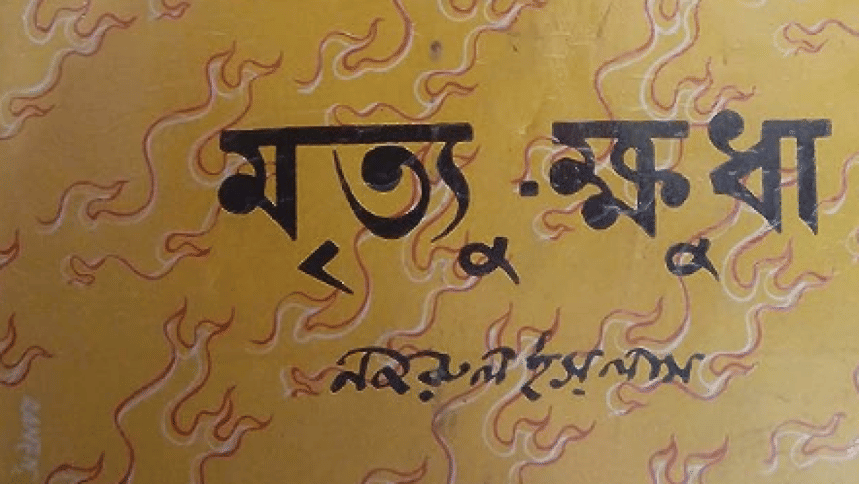

MB: It is worth considering that there is already a re-figuration of the limits of Muslim identity as it pertains to religious faith and political affiliation, in response to the neo-Hindu trends of masculine communitarian politics that emerged in the last three decades of the nineteenth century. Bengali Muslim reactions to this centring of the normative Hindu imaginary need more thoughtful consideration and recuperation. The visibility of Christian missions in rural Bengal in the second half of the nineteenth century, the financial and political resources expended on evangelism and conversion efforts, the implicit racial hierarchies practised by the missionaries and colonial officials, and the explicitly insulting nature of Christian apologetics, especially about the Prophet, created an impression in the Bengali Muslim ecumene of a much larger threat of Christianity. Some of this is documented in Nazrul's poignant novel about Muslim converts to Christianity, Mrityu Khuda.

The social and economic changes wrought by the passage of the Bengal Tenancy Act of 1885 were also important in this context. After a series of rent strikes, the depositions of the landlords, largely high-caste Hindus, failed to convince the colonial administration of the wisdom of non-interference in the relationship between raiyyat and zamindar. The Bengal Tenancy Act invested "the raiyati layer of the right to the land with substance and security". With the Bengal Tenancy Act of 1885, and a corresponding waning of the zamindars' rent offensive, the Muslim peasantry found a new economic and social stability. This shift in the domain of material life opened the conditions of possibility for the flowering of new subaltern discourses on religion, culture, social hierarchies, and resistance against suspected efforts at depredations of social cohesion through evangelical Christian missionary activity.

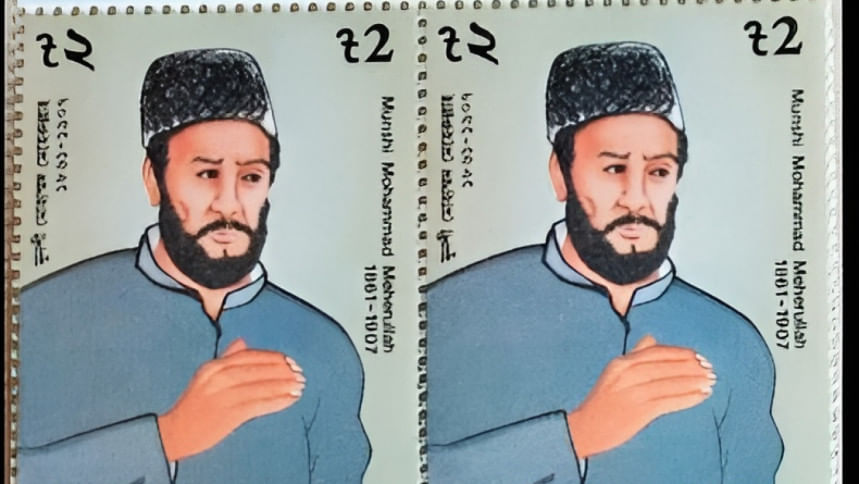

The man whose anti-Christian and anti-conversion activities were at the heart of such reconfigurations of Bengali Muslim identity was a charismatic tailor and preacher called Munshi Meherullah. From the numerous obituaries published after his death, it is clear that Meherullah's opinions about Christian evangelism had found resonance in a wide subsection of rural peasant society. Meherullah's acceptability as a spokesman for the religious, political, and social aspirations of Bengali Muslims was acknowledged by the centres of high intellectual exchange in Calcutta and Dhaka through the print medium.

The Bengali Muslim public sphere, aided by the print media, helped disseminate Meherullah's opinions, especially to the educated ashraf or elite Muslims. This was done by allowing him the space to write and contest Christian evangelical polemics in the pages of fairly widely subscribed periodicals and pamphlets, most of which were straightforward transcriptions of his speeches. Meherullah's characteristic apologetics against Christian evangelism translated into the print medium with vibrancy and humour. For example, his Jawabunnesara or Answers to Major Theological Questions Used by the Missionaries in an Effort to Critique Islam, written in 1898, took the form of a dialogue between a Christian missionary and himself. Meherullah's relentless apologetics against Christian evangelism and conversion efforts stemmed from the recognition that in many cases, Muslim conversions to Christianity were the result of the wretched conditions of existence in rural Bengal. The general lack of medical care, access to education or employment, and the often unprofitable business of agriculture that was at the mercy of moneylenders and erratic weather, exacerbated the situation. Missions provided education, employment, and medical care, which were fundamentally important services.

Meherullah, in his capacity to travel across networks of information exchange, from the elite ashraf circles of the Mihir-o-Sudhakar in Calcutta to the bahas and waz-mahfils of the villages and mofussil towns of rural Bengal, complicates our notions of who could speak for the community and the nation. In fact, Meherullah's imagined community is one that envisages rural Eastern Bengali Muslims banded against Christianity and colonialism, and this opens up an interesting arena of processual understanding for rights and identities. He was an interlocutor of his social milieu, mediating between the present and the past in a voice that could not be drowned out by the larger intellectual currents of nationalist historiography that have privileged the Hindu/Brahmo point of view. Meherullah possessed what Ranajit Guha called "the small voice[s] of history", recovered from the ruins of the vernacular pasts.

The refiguration of Muslim identity in Bengal, positioned against the depredations of missionary-led conversion efforts, hardened further in intellectual contests on cow-protection between towering Bengali Muslim intellectual figures like Mir Mosharraf Hossein, Moulavi Naimuddin, and Reazuddin Mashaddi of the Sudhakar group. What is clear from the life-worlds of the rural Bengali Muslim peasant milieu that we can reconstruct from archival documents and ephemera is a complete remaking of Muslim identity, positioned against religious Others. Articulated through differences of ideological engagements between the Hindu/Christian "Other" and the Muslim "Self", the apologias of the kind we see in the Sudhakar, Akhbar'e Islamia, and other pamphlets sought to delineate and ascribe primacy to Swajati vs. Swadesh—imagined community vs. idealised nation.

The interview was taken by Priyam Paul.

Comments