Disgruntled with a cause

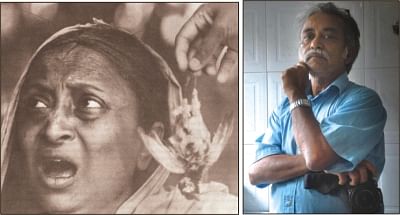

Rawshan Jamil in Shurjo Dighal Bari (left) and Anwar Hossain (right). Photo: Mumit M.

Though internationally renowned as a photographer, Anwar Hossain's contribution to Bangladeshi films is no less profound. Consider the critically acclaimed films made in Bangladesh; several of them feature Anwar's signature cinematography -- Shurjo Dighal Bari, Emil-er Goenda Bahini, Puroshkar, Dahan, Hulia, Chitra Nadir Parey, Nadir Naam Madhumati, Laalshalu and Shyamol Chhaya for instance.

Anwar has not stopped working as a cinematographer. Based in Paris since 1993, he comes to Bangladesh frequently. His most recent project: Tanvir Mokammel's film Rabeya.

"I originally wanted to be an artist," says Anwar. In the early 1960s Anwar had eminent artist Debdas Chakrabarti as an art teacher at school. Anwar's creative flair was recognised at school. But fate in the form of a disapproving family intervened. Born into poverty, Anwar was the first in his family to complete the entrance exam (equivalent to SSC). Despite all limitations and difficulties, he stood fifth in the exam and Anwar had to give up his dream of becoming a painter. He studied architecture instead. "It was more like a compromise," says Anwar.

It seems that regret eventually made him what he is today. According to Anwar, "I took up photography as I couldn't pursue painting." He bought his first camera from a friend in college on instalment. An ICCR scholarship to study at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in Pune however, pushed him more towards photography. "The first three years at FTII included still photography," he says.

In 1980, with Sheikh Niyamat Ali's film Shurjo Dighal Bari, Anwar stepped into the world of cinema. Anwar's innovative working technique behind the lens provided the film with a true to the core rural look. The film is considered a groundbreaking effort in Bangladeshi cinema.

Speaking on the gradual changes in the Bangladeshi movie industry, Anwar says, "In the post-Liberation War Bangladesh, there was no standard work procedure. There were random efforts -- certain actors were talented and certain government officials were helpful. This haphazard system hasn't changed much."

A disgruntled Anwar blatantly continues, "Except for a few, people who are involved in our movie industry are semi-literate/ illiterate -- both academically and intellectually. There are filmmakers who are SSC dropouts. How do you suppose the mass taste will develop?

"There has to be laws and regulations that ensure that 'uneducated' people cannot work as technicians and filmmakers."

About young filmmakers, the noted cinematographer says, "There have been certain interesting efforts but unfortunately I haven't seen brilliance. Quite a few of these young filmmakers are film buffs and have good intentions, however I believe a good food critic is not necessarily a good chef."

When it comes to filmmaking and cinematography, Anwar has more reasons to be irate. "Quality often takes time and patience. Consistency is also a key element. Shurjo Dighal Bari was shot in sixty days. Now we're given twenty days to wrap things up. For instance, while shooting the film Rabeya, I said that I needed seven to fifteen dusks/ dawns. I was given two days. I could either say no or make compromises. And I sadly noticed that schedules of filming are revolved around actors/ actresses.

"We had to wait for an actress with negligible talent so that she could make some time for us; she was busy working in TV serials. There is no professionalism."

The renowned photographer is not happy with the photography scene in Bangladesh either. "How many photo exhibitions are held on national level in Bangladesh?" -- Anwar asks. "There is no photography department at Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy. Apparently 'Chobi Mela' is an international festival of photography. I haven't been invited to this festival as of yet," he adds.

Anwar's suggestions: "The Bangladesh embassies should take copies of ten best films and screen them around the world. There should be an institute for cinematography and photography. A certain standard should also be ensured when it comes to filmmaking. Films that receive national awards should be declared tax-free. Good films can flourish if the government can ensure proper distribution. TV channels should air them as well."

Despite the frustrations and unrequited hopes, Anwar has not given up. Perhaps it is time for the film industry to live up to these expectations.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments