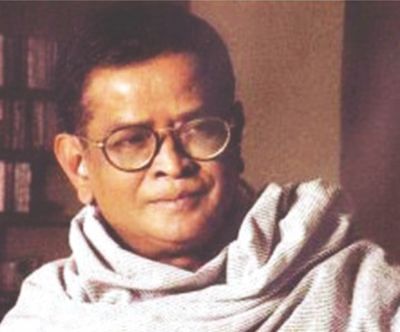

Humayun Ahmad: Man and writer

My meeting with Humayun Ahmed this year, when he came for a few weeks to Bangladesh before returning to the United States to resume cancer treatment, was the first and last time I met him. Apart from his short hair in public he had taken to wearing a hat, but did not have it on at home there was nothing to suggest that all was not well with him. In fact, he looked so unbelievably well that I was sure that, after completing his course of treatment, he would return to his former self and productive life. Sadly, that was not to be.

I had heard about his love for food and his gracious hospitality, and I experienced it at first hand. After answering most of the questions that I had noted down I am in the process of translating his novel Maddhyana and had some queries on that for him he offered me tea and snacks. There was a plate of monda a sweet I am particularly fond of but, for whatever reason, I politely declined. He asked me if there were health reasons why I couldn't take sweets. When I said no, he urged me to try it. It was good, he said. I took it and, yes, it was good.

There were a lot of people in the room and I realized that I should leave to allow others to speak to him. As I got up to leave, he gave me Bhoy, a collection of three stories focusing on Misir Ali. You might like it, he said.

That was the first and the last time that I met Humayun Ahmed.

Of course, like most Bangladeshis I knew about him. Had seen his television serials and had read a few of his short stories. Had in fact, written to him on a number of occasions for permission to translate a short story or to include a translated short story in an anthology. Always he had given permission. There were also a number of book launches of these anthologies, but he could not attend any.

I am not sure whether I became acquainted with him through his television plays or his fiction first. Perhaps it was simultaneous. But while I enjoyed the television plays, his short stories drew me to his writing. I must confess that my interest in his short stories developed indirectly rather than directly. A sister-in-law (nanad) of mine used to be an avid reader and was fond of sharing what she had read with me. She suggested that I would enjoy Humayun Ahmed's short stories. I got a copy of Shrestha Galpa and discovered that Humayun Ahmed was indeed a master of the craft of the short story. As Rabindranath Tagore has said, short stories are about seemingly small incidents, about small joys and sorrows, but which leave an impression on the mind. Humayun Ahmed's best short stories exemplify Tagore's description:

Chhoto praan chhoto kotha

Chhoto chhoto dukkho byatha

Nitanto-i shohoj shorol

Nahi bornonar chhota

Ghotonar ghonoghota

Nahi totto nahi upodesh

Ontore otripti robey

Shango kori mone hobe

Shesh hoye hoilo na shesh.

(Little souls little tales

Little pains and pangs

Merely simple in the telling

No elaborate description

Only a narrative of events

No theory no advice

The thirst remains unquenched

Once done the feeling rises

It ended and yet did not end.

(Translated Syed Badrul Ahsan)

The first story of Humayun Ahmed's that I read and translated because I could not get the scene of the eater out of my mind was "Khadak." It is the story of a man who eats so that his audience might derive pleasure from seeing him defeat his rivals. Told through a narrator, who is not the protagonist but a witness as in several of Humayun Ahmed's short stories (perhaps the influence of Somerset Maugham, who used this device in his fiction) the story ends with the eater continuing to eat while his hungry children look on. Will there be a happy ending? The narrator asks. Will the eater stop eating and give the food to his children? But no, he continues to eat. There is a moral to the story, a social critique, woven subtly into it. The English translation was published in an issue of the Bangla Academy Journal and picked up by the compilers of Voices, a literary magazine published by expatriate Bangladeshis in the US.

Other stories which I read and translated myself or requested others to translate for anthologies included "Ayomoy," "1971," "Jalil Saheber Petition," "Aparanha." "Ayomoy" which has nothing in common with the television serial of the same name is about the relationship between a rich zamindar and an ailing man. It is the month of Ramzan and the zamindar is busy with other matters, He does not want to bother about the poor, sick man to whom he is a reluctant host. He is told that if the man is made to do "taoba," he will die quickly. The imam of the mosque is sent to carry out this ritual and he does so. But the man does not die. It seems that the man does not want to die and therefore only pretended to do "taoba." Finally, the zamindar's attitude to the man changes. If the man is so determined to live, he deserves to be saved. He therefore decides to take him to town for proper medical treatment and care. In the space of a few pages, the short story deals with class differences, religious rituals, superstitions, human relations, and above all, with human resilience.

Both "1971" and "Jalil Saheber Petition" are about the Bangladesh Liberation War: the former taking place while the war is still raging, the latter several years after it is over. Both are classics: "1971" in showing the indomitable courage of an unarmed Bengali civilian faced with the might of the Pakistan military and "Jalil Saheber Petition" in showing the plight of a father who has lost both his sons in 1971. All Jalil Saheb wants is that people recognize the sacrifices of his sons and others like them in 1971. He goes around with a file under his arm. At the beginning the narrator finds him somewhat of an eccentric nuisance as perhaps readers do. The narrator goes abroad. He returns to find the man is dead. He thinks that he will take up Jalil Saheb's work. But he never does, involved he becomes with other activities. Thus Humayun Ahmad indicts all of us who have benefited from the sacrifices of the freedom fighters and their families but remain silent or indifferent.

Another thought-provoking story is "Aparanha," about the death of a rickshawallah. For the last few years, rickshaws have been banned from several streets in Dhaka, but a few years ago rickshaws were a common mode of transport. Humayun Ahmad's short story about the rickshawallah was so true for all of us who have ridden or still occasionally ride rickshaws. The way we haggle with rickshawallahs, trying to bring the fare down, as well as our complete indifference to the individual who is pedalling the rickshaw is brilliantly touched upon by the author. It is a sad story the rickshawallah dies but there is also humour in it as the narrator asks another rickshawallah before he hires him what his name is, whether he is well, etc. He doesn't want this rickshawallah to die on him again.

For a number of years, whenever I compiled an anthology, I would include Humayun Ahmad's short stories. Then, for whatever reason I stopped. Then last year, I was approached with the request to translate Maddhyana. I hesitated. I had translated short stories, but had never taken up a novel. Did I have the time to translate four hundred pages? But I could not say no. After all, Humayun Ahmad had always readily given me permission to translate his stories and include them in anthologies. So I agreed, but with the stipulation that I could not do the whole work myself but would collaborate with another translator.

Yes, the first draft of the translation of Maddhyana.is finished. That is why, when I met Humayun Ahmad, I was able to discuss it with him. Some of my questions had to do with style, some with content. Bangla fiction, for example, uses the present tense for narrative, English the past tense. Which would he prefer we use? The present tense, he said. What about quotation marks? Bangla fiction does not use quotation marks, English does. Use quotation marks, he said. As I revise what my co-translator and I have done, I am putting in these changes. But there are other questions that remain unanswered because he wanted to think about them.

I am sorry that he isn't around, sorry that I couldn't give him the finished translation, sorry that the questions he was going to ponder over before responding will remain unanswered, sorry that we never did get to talk about the title. But I want to thank you, Humayun Ahmad, for your short stories, for your plays, for your movies and for obliging me to read this historical novel about Bengal during the third and fourth decades of the twentieth century.

I would like to end this tribute by quoting from the American poet Walt Whitman: "The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it." If there is any need to evaluate how Bangladesh has absorbed Humayun Ahmad, we need only to remember the scenes at the Shaheed Minar where multitudes thronged to pay their last respects to the writer who had entertained them for forty years and who had inspired a whole generation to read Bangladeshi books.

(Humayun Ahmed's birthday was observed on 13 November)

DR. NIAZ ZAMAN IS AN ACADEMIC, WRITER, CRITIC AND TRANSLATOR. SHE IS A MOVING FORCE BEHIND THE LITERARY GROUP, THE READING CIRCLE #

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments