Decolonising the cities to address flood, rain and water

The city is conceptualised in many different ways – as a body, a machine, an organism, a second nature and now a third or even fourth nature. These readings of the city, however, have been based on the idea of the city as dry ground separated from water, an unstable element that needs to be managed or controlled. Indeed, the city's relationship with water is defined by how the latter is contained as an entity, whether as a 'river', 'sea' or in pipes and drains. The present condition of the cities in the Bengal Delta, a monsoon-fed landscape, exemplifies this simplistic articulation of 'land' and 'water'. For over 200 years, since the British colonial period (1757-1947), urban development involved confining the delta's constantly shifting waterways to create 'dry' land through the lines of rivers, canals, embankments, colonial structures, railways, etc., and it has been continued with the same mentality in the present.

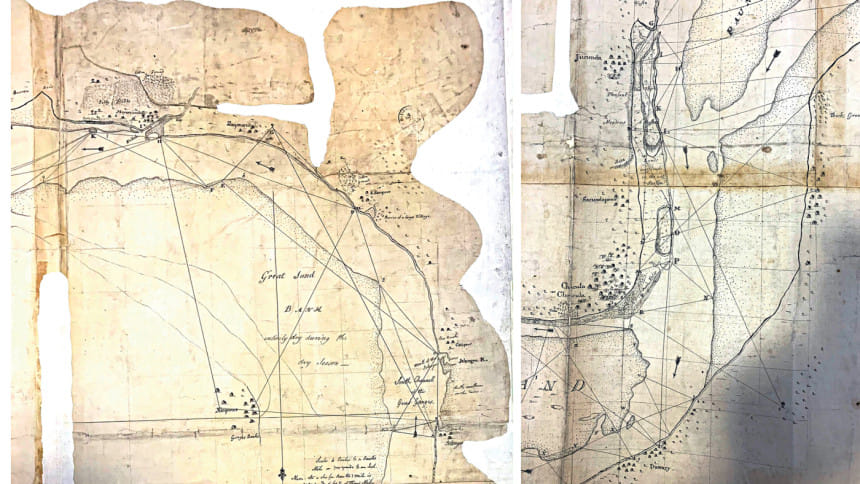

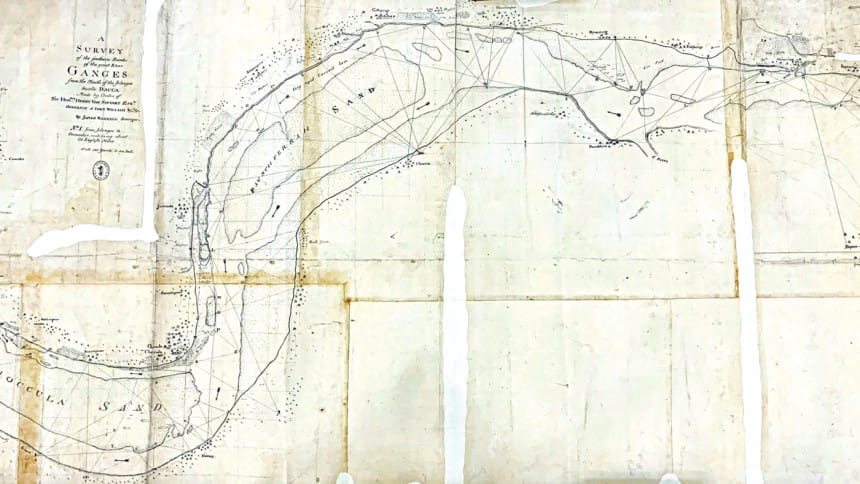

The discourse of 'contained water' and 'dry ground' in Dacca (now Dhaka) was brought about through a series of colonial practices and interventions. In the early colonial period, the dynamic landscape of the delta – its shifting rivers, disappearance of lands, and accretion of new lands – was perceived as a hindrance in the functioning of territorialisation, governance and taxation. Through mapping the colonised territory, enacting different laws and regulations and implementing infrastructural projects, the colonial government constructed bodies of knowledge about the deltaic landscape that allowed it to exert its power and promote profit-extracting activities. At the same time, influential natives (merchants, zamindars, etc.) were also engaged in those projects, using them to serve their own interests. Historian Debjani Bhattachharya argues the interventions ultimately led to the 'soaking ecology' that is long inherent to the delta being forgotten. These interventions also contributed to a pervasive separation of land and water, making these categories of landscape seem so self-evident as to escape our ability to even question their very existence. These geo-cultural transformations created a complex tradition of seeing and representing the city and the landscape that came to be shared by both coloniser and colonised.

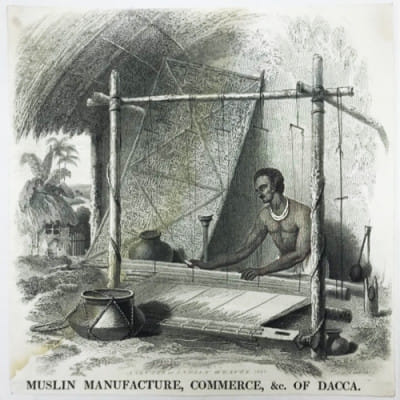

One of the major aims of the postcolonial discourse is to identify the continuing threads of exploitation from colonial to postcolonial period. Now the questions to ask are, how was the colonial land-water separation a mode of exploitation and how has this been continued in postcolonial Bangladesh? These questions are important as they are deeply connected with the way we perceive our cities, treat our waterbodies and address floods. Think of our spinners and muslin weavers who were dependent on the watery landscape to weave the finest quality of muslin fabric. The extreme delicacy and thinness of muslin fabric, for which it once gained its worldwide popularity, was dependent on the presence of moisture in the atmosphere. This moisture is another form of water which is not visible in the way we imagine water today. And this damp, moist atmosphere was a result of the presence of forests, waterbodies and monsoon climate.

However, the clearing of forests and marshes which started even before the British arrived in Bengal in fact accelerated in an unprecedented manner under the East India Company for whom the revenue from the land was of utmost priority. The enactment of laws like Permanent Settlement Act of 1793, Bengal Alluvium or Diluvion Act (BADA) of 1825 among many others was crucial to formalise the division of land and water, and to maximise the area of cleared land for cultivation and earning revenue. As the forests were cleared and water and land got demarcated and formalised, the required moisture for muslin weaving was lost. Many weavers had to convert to agriculture and other professions at which they were not adept. As a result, many of these weavers died due to the famines during the late 18th to the early 19th century in Bengal.

In a more recent work, landscape architect Dilip da Cunha argues that the line with which maps are drawn, and land and water are separated, is a colonising device that subjugated indigenous people and created an 'underclass'. In that sense, defining this 'dry' form of land and 'contained' water in the colonial period was a mode of exploitation because of which these indigenous people suffered profound dissonance as their experience was grounded in the water cycle in one moment, but they were made to inhabit another. Historian van Schendel refers to the presence of water-based artisan economy in Bengal existing before the colonial period. Through the profit-generating activities of the colonial administration, rice cultivation was made the universal occupation for the 'underclass' supplanting many diverse indigenous artisan practices. The colonial interventions on the landscape not only impeded muslin weaving and other artisan industries, but also cleared the path for further exploitation and discrimination.

What is the current status of this particular form of 'land' and 'water' and how has this dividing process been continued in postcolonial Bangladesh? The idea of the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793 ensured that any embankments built by local zamindars will be incentivised as these structures unambiguously represent the line that clearly demarcates the division between land and water. Similar trends can be traced in the huge national interest in building dams and embankments which are often incentivised by international and world organisations. Prior to every election, it is a common rhetoric to promise more embankments in the name of development – controlling rivers and addressing floods. In his seminal work, postcolonial thinker Frantz Fanon pointed out how the colonial discourse generated desire among the others (colonised) to be like the Europeans or Westerners. This is one major continuing thread in the transition from colonial entities to postcolonial nation-states. The political rhetoric of building embankments makes us believe that embankments are a symbol of modernity, and that we will be more civilised if we have more controlling measures. We want our Buriganga riverfronts to look like Thames! This is the desire that overpowers the critical questions such as "What does climate require?" and "What should be the nature of cities in this monsoon-fed landscape?"

Each year we manage to build a number of dams and embankments. However, the cities received most importance not only because they accommodate the majority of the population, but also because of their centrality in this commerce-driven society. In the process, the non-urban settlements and their inhabitants were marginalised. The more embankments built in one location, the higher the impact elsewhere. A widely shared piece of news recently was the drowning of the three-storied Shibchor Model High School as Padma shifted about few miles overnight. This is an appropriate example. On the other hand, since the cities are compartmentalised they become waterlogged during every monsoon. Yet some of us who are privileged enough to remain high above the ground and can afford to be at home, try to celebrate rain with khichuri and Rabindra Sangeet. But as soon as we step outside, we only curse the rain and our cities. A profound contradiction in our daily urban life!

Surely, in the age of climate change and rise in sea level, embankments cannot be the long-term solution and are not an appropriate measure for a country like Bangladesh, which is still developing and located in the world's largest Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta, a monsoon-fed landscape. Regular occurrences of water-logging within the city and the disappearance of structures and lives in non-urban/semi-urban areas point out the problems of such hard-engineered thinking. Moreover, it is such hydrological infrastructures that give rise to inequalities.

If embankments are not the solution, then what is? There is no straight-cut answer or mathematical formula if we acknowledge the context with its complexities. However, the process to address this problem involves decolonising our city-thinking and landscape-thinking. It starts with acknowledging our colonial history and identifying the false desire that it generated and continued to generate in the postcolonial context. It leads us to connect the thread between colonial land-water separation and the way we perceive our cities and landscape now. Certainly, in Dhaka, water, a natural element, has become our enemy and flood, a natural event, has become a curse. But are they as 'natural' as they seem?

Each year during June and July, the monsoon wind brings rain that fills and overflows our water arteries. We call this overflow flood, but our 'modern eye' tends to seek where exactly this overflow occurs. Theoretically, it is at the line where water ends and land starts. Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha argue that flood is water crossing a line that is drawn by us, humans, and thus, flood is not naively 'natural'. If we can question the line, we can question the existence of 'flood'. Rather, what we call 'flood' is the excess of water in the terrain, which will flow and evaporate in the atmosphere. To let this happen we need to rethink the ground of the cities – which does not confront water, rather welcomes rain and water, soaks the excess and lets it evaporate. We need to find ways to soften the existing hard lines and to restore the forgotten soaking ecology.

It is also necessary to bring in the monsoon experience of local people by envisioning an ecological scale that goes beyond the city-village binary. This is the 'decolonising' call for our cities to address water and flood. At the same time, as many scholars argue, 'decolonisation' is a slow process and cannot or should not be addressed with a quick solution. It requires a fundamental change in our thinking and ways of perception and a whole mode of cultural shift. In other words, it is a transdisciplinary holistic task that needs involvement of other disciplines. Thus, in our future urban-water-planning projects, the government needs to ensure involvement of different sectors, not just politicians, engineers and urban planners, but also historians, anthropologists, architects, writers, critical thinkers as well as community people.

Labib Hossain is a PhD Fellow in History of Architecture and Urban Development at Cornell University and a lecturer (on leave) at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET). He can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments