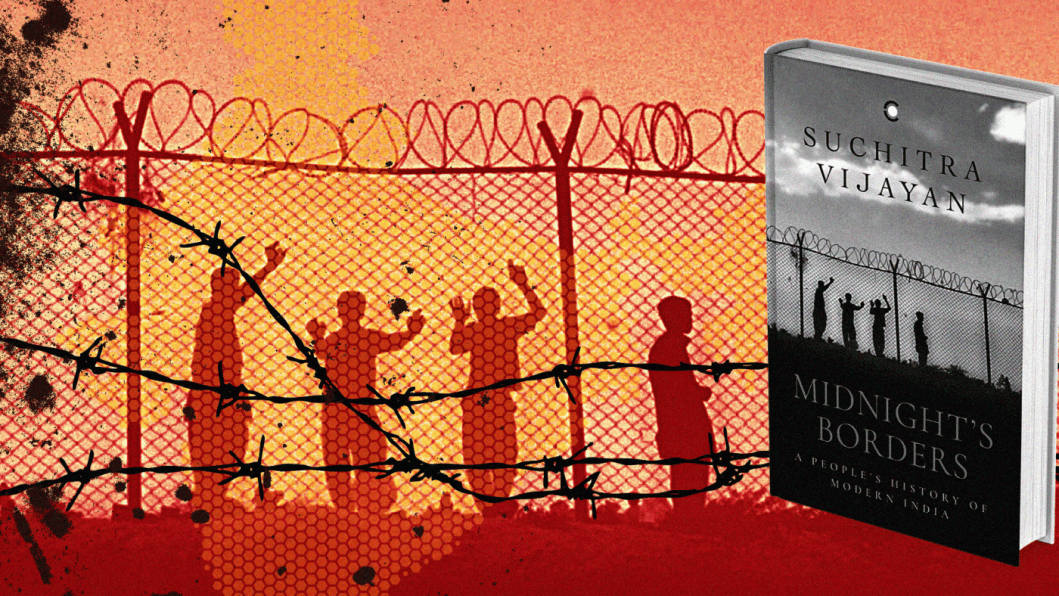

In Suchitra Vijayan’s new book, borders are as arbitrary as history

What is the difference between a border and a frontier?

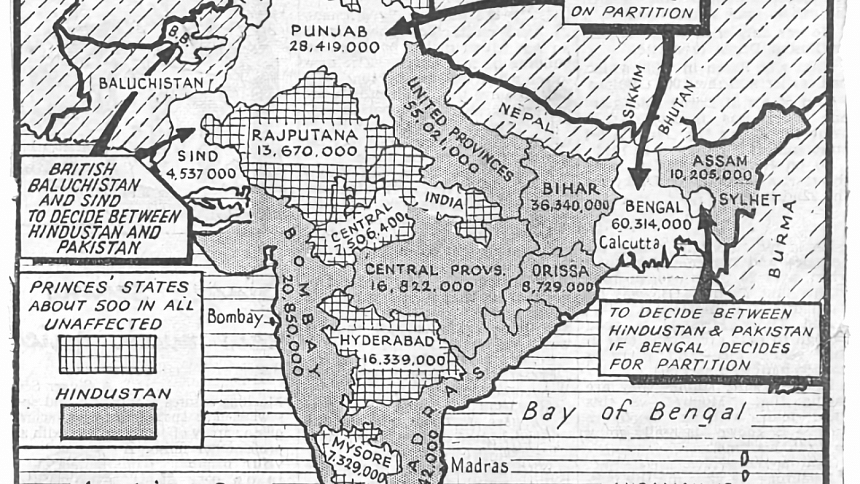

Upon assuming control over India in 1858, for 190 years, the British Crown would segregate a syncretic subcontinent along the faultlines of religious differences, stoking unrest between its Hindu and Muslim communities. These 300 million "colonial subjects" would never be given the right to self govern, or vote across the religious divide. Famines, failed mutinies, and conscription of civilians as pawns in the West's power plays would go on to colour this history. As the hour of freedom from colonial rule approached, frontiers are what the newly independent nation deserved and hoped for—frontiers in the sense of boundaries that promised security and potential.

But the 15th of August, as we know, caused a different kind of unleashing in 1947, transforming some 17.9 million civilians into migrants scurrying across the Indian subcontinent, divided now into India and East and West Pakistan. In Midnight's Borders (Westland Publications, 2021), author and photographer Suchitra Vijayan travels the 9,000 miles of India's borders to understand what Partition did to individual lives and communities, and how it continues to incite violence, displacement, prejudice, and trauma among those who live in the border regions. Vijayan treats these regions as frontiers, using them as points from which to reach into each area's internal (and historical) conflicts as they were triggered by the Partition.

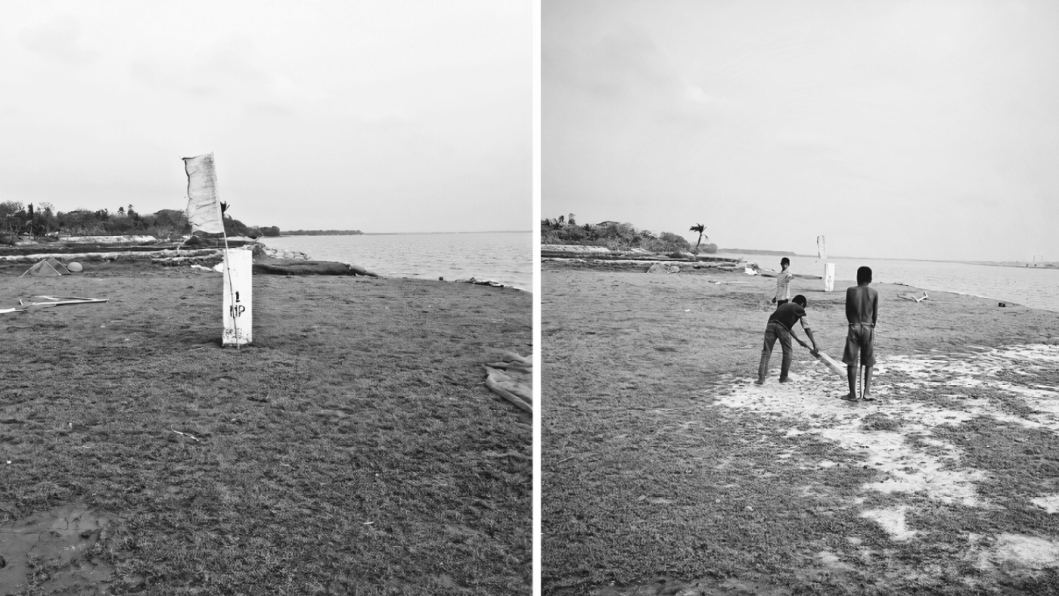

She interviews militants, soldiers, border guards, and civilians—children who play cricket along the Bangladesh-India border, families who have lost a child or a spouse. For this book, she groups the interviews into chapters demarcating each of India's borders with Afghanistan, Bangladesh, China, Myanmar, and Pakistan, the latter expectedly touching upon the most contested issues relating to Kashmir and Rajasthan. If the first chapter on Afghanistan begins from the initial stirrings of colonial ambition in the 18th century, when the geopolitical expanse of Russia threatened the British into demacartating the Durand Line, her last chapter in Amritsar circles back to another epoch-making event of history when, on April 13, 1919 in Jallianwala Bagh, British brigadier general Reginald Dyer ordered the massacre of unarmed civilians who had gathered to celebrate Baishakh. Between these bookends, history churns in the form of trauma in this text, each killing, each misinformed policy begetting death, disappearances, orphanhood, emotional and physical abuse, enforced prostitituion and cultures of smuggling, and deliberate amnesia among generations of those affected.

The most fundamental action of the Partition—the drawing of the lines—occurred under famously irresponsible circumstances. When British lawyer Cyril Radcliffe landed in the subcontinent on July 8, 1947, he had seven weeks to complete the cartography of a region he had never before visited, whose mosaic of languages, cultures, and communities he was unfamiliar with; the maps and census data he consulted were out of date. Vijayan quotes an interview given by Radcliffe to Kuldip Nayar, in which he admits, "If I had two to three years, I might have improved on what I did". But, as she highlights, this was not the first time. The Durand Line drawn in 1893 sliced through the Pashtuns, Baloch, and other ethnic communities residing in the Pashtun-Balochistan regions; the McMahon Line descends from an agreement between Britain and Tibet that continues to be contested by India and China today.

The history that Vijayan very cleanly, but briefly, recounts in her book would be more insightful for an audience unfamiliar with the subcontinent's past. For those of us who have lived and descended from it, the individual stories she unearths can be more jarring.

Near the river of Mahananda which divides Bangladesh and India—600 yards away from the town of Tetulia and another 40 miles east—Vijayan talks to a man named Ali who lived near a pond through which Bangladesh-India's zero point runs. When India constructed a border fence 150 yards from the zero point in 2007, Ali was stuck in the accidental no man's land. A local leader convinced him to sign papers testifying that he would be okay with the floodlights being installed close to his home. Its orange beam blasted through his house. Ali could no longer sleep, fatigued and depressed, fainting at work, slurring speech, facing panic attacks and mild paralysis in his left arm. Following a complete mental breakdown, he plastered up every surface of his home and took to living in complete darkness, sequestered from regular living.

In her mining of these stories from each of India's border regions, Vijayan reveals a thorough grounding in the ethics of retelling others' experiences, in a way that is reminiscent of Aanchal Malhotra's research with the Partition's material memory. Like Remnants of a Separation (HarperCollins, 2017), in which Malhotra interviews Partition survivors about the physical objects they travelled with and stored their memories in while fleeing the communal unrest, Vijayan, too, tries to piece together a traumatic past from memories, old letters and family albums, monuments and shrines, and official documents. But whereas Remnants was a work of fine art, shaped primarily by the subjects' sentimentality and deeply personal remembrances, in Midnight's Borders Vijayan involves the state and military forces in the conversation, and keeps her own tone as narrator more matter-of-fact.

She takes an event—the killing of 24-year-old Hilal Ahmed Dar in Northern Kashmir in 2012, for instance—and takes its details to the concerned family, their friends, their neighbours, and the state prosecutor and army officials, juxtaposing the contradictions in each version of events. She addresses the questions asked and the refused answers. And the images she was requested not to share. "The people in this book are eloquent advocates of their history and their struggles. My role, then, and this book's role, is to find in their articulations a critique of the nation state, its violence and the arbitrariness of territorial sovereignty", she writes in one chapter. In another, regarding the cruelty acted out by border guards, she asserts, "These men are not inherently evil, wicked, sadistic or vile. Yet [...] the constant reinforcement that the borderlands are a different space, a contentious space, [...] where order must be established through force, enables exceptional acts of coercion and violence."

At the beginning of the project, which spanned seven years, Vijayan was an attorney who had worked for the United Nations War Crimes Tribunals for Yugoslavia. Her interest in the testimonies of victims and survivors, even if driven by compassion, seemed purely intellectual and professional. Over the course of the journey, however, the author watched her father grapple with a serious illness and gave birth to her first child, and her heightened, urgent need for a safer world seeps through the writing as she uncovers each patch of India's borders for us. Her censure for the arbitrariness of its injustices grows more pronounced.

In one of the last chapters, titled "Rajasthan: The Tyranny of Territory", Vijayan stands atop a BSF watch post overlooking the "air tight" border separating India and Pakistan, but the cadences of an azaan waft over both regions. As with the tides drowning gangetic deltas appearing in an earlier section on the Sundarbans, the text seems to highlight the pointlessness of much of the violence of human history, all of which is ultimately silenced by the forces of nature.

A border, not a frontier, is often a cage. The project of this book—and of remembering the legacy of Partition—is at least partly about realising its porousness.

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected], or on @wordsinteal on Instagram and Twitter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments