Art films

From the definition provided at Art House (Definition), "Art house is a film genre which encompasses films where the content and style – often artistic or experimental – adhere with as little compromise as possible to the filmmakers' personal artistic vision."

Essentially, in layman's term, an art film is a director's baby with no cuts or forceful inclusions from producers as in most cases; the director himself is the producer. Its content is mostly serious, ideas free and independent and targeted towards a niche audience lacking mass appeal.

Art films are predominantly aesthetic, with symbolic and unconventional content and are not made with commercial profit in mind. With shoe-string budget and other constraints like lesser known actors, these hardly ever acquire blockbuster status barring a few. But they are an attempt to develop new ideas and to explore different narrative techniques with wide experimentation in cinematography.

These movies are debated time and again over cuppas for days on end and post-mortems and critiques are done to the last bone. And that is how the masses come to know of them.

To promote their masterpieces, art film directors rely heavily on the publicity generated from film reviews; discussion by film columnists, commentators, bloggers; and word-of-mouth comments. By sheer luck, if the film gets mentioned in the acclaimed film festivals, it is altogether different then.

Although, art films at times are considered better than the mainstream or commercial movies, such comparisons are downright naiveté. Sometimes, the fine line between the art and the commercial movies are broken and the two genres merge blurring distinctions.

In today's multiplex culture world, a film can be made artistically to make it commercially viable. However, film scholar, David Bordwell describes art cinema as "a film genre, with its own distinct conventions".

The term art film was more widely used in North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia, whereas in the mainland Europe, terms like auteur films and national cinema (German national cinema) were used instead. Again, in the Indian sub-continent, art films are generally referred to as parallel cinema.

Previously, art films were screened at theatres where the owners took it upon themselves to screen them or in special repertory cinemas in the USA. But with the mushrooming of multiplexes, slowly this has narrowed down. However, one needs a certain degree of knowledge and intellect to fully appreciate these movies and delve into them.

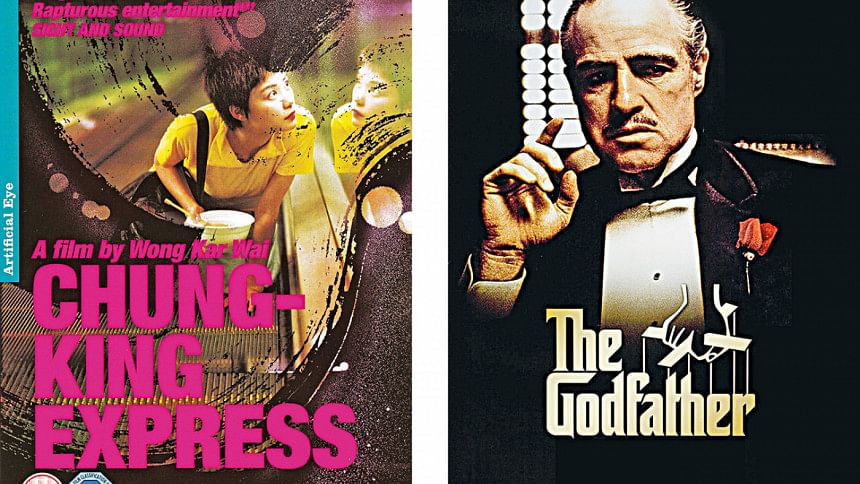

Film critic, Roger Ebert said about Chungking Express, a critically acclaimed 1994 art film, "largely a cerebral experience" that one enjoys "because of what you know about film" in the Chicago Sun Times.

Europe takes the lead when art film is talked about. Italy with the silent L'Inferno in 1911 etched a mark in the art film firmament. Russia's Sergei Eisenstein, followed suit in inspiring European cinema with his Battleship Potemkin (1925), a revolutionary propaganda film where he experimented with film production to the hilt.

Avant-garde Spanish and French filmmakers took art film a notch higher. Salvador Dalí and French Jean Cocteau use oneiric images in their experimentation creating amazing silhouettes. 1920s and 1930s saw French Cinéma pur, dominating the scene.

Cinema pur had Dadaists, who excelled in transcending narrative storytelling by creating a flexible montage from bourgeois traditions and Aristotelian notions.

When Europe was busy creating abstract movies, Hollywood art scene had mostly literary adaptations. But in the late '40s, after the end of World war II, when Europe had surged ahead in the new movement, Hollywood woke up to new ideas finding people more drawn towards the arthouse genre.

Although Italian Neorealist movement, French New Wave Movement continued into the '60s, the term art movies gained prominence in the USA more than in Europe then.

From the '80s to the beginning of the millennium, art film in the USA meant independent movies which was experimental but raked in moolah with huge funding from the film production houses. In 2007, Professor Camille Paglia argued in her article "Art movies: R.I.P." laments that "[a]side from Francis Ford Coppola's Godfather series, with its deft flashbacks and gritty social realism, [there is not] a single film produced over the past 35 years that is arguably of equal philosophical weight or virtuosity of execution to Bergman's The Seventh Seal or Persona".

THE SCENE IN ASIA

From the mid-1940s, when the Italian neorealist were producing classics like Open City (1945), Paisa (1946), and Bicycle Thief dubbing them as "conscious art film movement", early '50s saw some great filmmaking from Asia.

India then was witnessing an art-film movement in Bengali cinema, labelled as "Parallel Cinema" or "Indian New Wave". An alternative to crass commercial films, these dealt with serious topics, largely dwelling on realism, surrealism and naturalism, talking about the changing socio-political milieu.

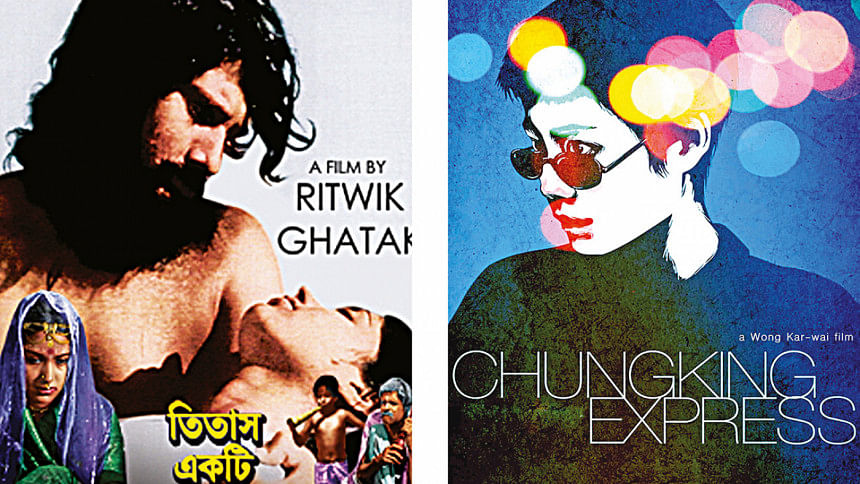

This happened around the same time as French and Japanese New Wave. The most influential filmmakers of these times are Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Tapan Sinha, and Khwaja Ahmad Abbas in the Indian subcontinent.

Satyajit Ray's directorial debut was with Pather Panchali, based on the autobiographical childhood story of Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay's novel with the same name. The film is a masterpiece and Ray showed the world how with very limited resources and absolutely amateur actors, he could create a gem.

Pather Panchali in 1955 opened to empty screens with most critics dubbing it as an effort to portray India's poverty to the western world. But Pather Panchali is much beyond criticism and is ranked at 12 by The Guardian (2010) as the best ever made art movie and is shown at most film institutes, where this movie is dissected thread bare for its sheer brilliance.

After winning the Cannes, Berlin and Venice film festivals, it is ranked one of the finest films ever made. Ray's Apu Trilogy (1955–1959), three films telling the story of a poor country boy, Apu's growth to adulthood and Asani Sanket, (1973), telling the story of a famine in Bengal are films of that golden era.

Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa in his Rashomon (1950), talks about four witnesses' contradictory accounts of a rape and murder. Through Ikiru, (1952), he talks about a Tokyo bureaucrat struggling in his meaningless life.

Tokyo Story (1953) by Yasujirō Ozu, explores social changes of the times. It is the story of an aging couple who travel to Tokyo to visit their grown-up children, but find them too self-absorbed to spend time with them. In 1969, Dariush Mehrjui's, The Cow deals with the story of a man who becomes insane after the death of his beloved cow, sparking the new wave of Iranian cinema.

With Asia's developmental pace taking off later than in Europe and the US, the1950s, 1960s and the 1970s saw a sudden change in societal norms and values with the population migration from villages to the big cities. And the films of Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Kurosawa, Ozu and other Asian directors spoke about pathos in their protagonist's struggle for existence.

CULT MOVIES

Taking cue from Europe, Asian directors too started making some of the finest pieces of art although the films had bizarre characters and imagery. Some films resonated intellectually, exploring philosophical and ethical issues. But with most directors, it was to each his own, like French Louis Malle chose moral path to exploration, dramatising his childhood experiences in Au revoir, les enfants, which depicts the occupying Nazi government's deportation of French Jews to concentration camps during World War II.

Directors in the 1990s explored philosophical issues and themes like identity, chance, death, and existentialism. Robert Altman's Short Cuts (1993) explores themes of chance, death, and infidelity by tracing 10 parallel and interwoven stories. These films with diverse thoughts and fascinating treatment remain cult movies.

However, some of the cult movies of all times, as listed by The Guardian are The Gospel According to Saint Matthew by Pasolini, Fanny and Alexander by the legendary Swedish filmmaker, Ingmer Bergman, Stephen Woolley's A clockwork Orange, Citizen Kane, Tokyo Story, L'Atalante, Andrei Rublev by Tarkovsky, Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali.

As of October 2017, Pather Panchali, has a 98 percent fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on an aggregate of reviews. In 2018 the film earned the 15th spot when BBC released the top 100 foreign language films ever.

Pather Panchali was included in other all-time lists, including Time Out's "Centenary Top One Hundred Films"

In 1999, The Village Voice top 250 "Best Film of the Century" critics' poll included The Apu Trilogy. The Apu Trilogy, Pyaasa and Mani Ratnam's Nayakan were also included in Time magazine's All-TIME 100 best movies list in 2005.

In 1992, the Sight & Sound Critics' Poll ranked Ray at No. 7 in its list of "Top 10 Directors" of all time.

These films have acquired cult status as they have inspired filmmakers and students across the globe cutting across linguistic barriers. Also, they did not remain merely for the intellectual's discussion but was widely accepted by the masses and went on to earn huge revenue. They are watched even today with as much enthusiasm and have outlived time warps.

BANGLADESH PERSPECTIVE

Dhallywood or films made in Dhaka actually took wings after independence. Although most films were made with the box-office in mind, some films stand out. Of the acclaimed directors, Fateh Lohani, Zahir Raihan, Alamgir Kabir, Khan Ataur Rahman, Subhash Dutta, Ritwik Ghatak, Ehtesham deserve mention.

After independence, one of the first international acclaimed film was Titas Ekti Nodir Naam released in 1973, directed by prominent Indian Bengali director, Ritwik Ghatak and starring Prabir Mitra in the lead role. Titash Ekti Nadir Naam topped the list of 10 best Bangladeshi films in the audience and critics' polls conducted by the British Film Institute in 2002.

Other notable films of 1970s include Joy Bangla (1972) of Fakrul Alom; Lalon Fokir (1972) of Syed Hasan Imam.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Bangladeshi film industry plummeted to great depths with unmindful copying of Bollywood potboilers and financial crunches. But then in 2012, government bailed out the industry which thereafter went on to make critically mentioned films like Monpura and others.

THE DECLINE: WHY THE YOUTH DOESN'T WATCH THEM

Camille Paglia states that young people from the 2000s do not "have patience for the long, slow take that deep-think European directors once specialised in…" These days, mainstream films also deal with moral dilemmas or identity crises which are usually resolved without much didacticism. It is a fast-paced instant age now and slow movies cannot keep up with the pace of youth mind. The attention span is shortening, so the films fail to make a mark.

One of the major reasons for the decline of the parallel cinema in India is that neither the Film federation nor NFDC looked at the distribution of art films. The mainstream exhibition system did not screen them for less entertainment value. The audience's intellect was never taken into account and only what a miniscule comprehended was forced on the audience.

To an extent, rise of TV is a threat to cinema and more so to the art films. Although it seems art film is dying a slow death, it should not be forgotten that filmmakers these days understand the pulse of the audience and hence every time there is a tendency to experiment. Some of these experimentations have resulted in Bollywood films like Barfi, which despite belonging to mainstream cinema was a visual treat.

IS THERE A CHANCE FOR ART FILMS?

Certainly, with the merging of the genres, art films will be commercially viable. The audience is mature and they crave for newer things. So, there is every possibility of a revival if the directors are also willing to work with low budgets with the fire and passion.

In the Indian sub-continent, the films must be shortened and editing must be trite to hold on to the attention span of the youth. Movies like Rituparno Ghosh's Utsab deserves mention in this regard. It falls into the parallel film genre despite being a box-office hit. Other films like these are Dahan, Yuva, Bas Ek Pal and others.

Internationally, too, some notable films from the 2000s possess art film qualities and differed from mainstream films due to controversial content like Gus Van Sant's film Elephant (2003), which depicts mass murder at a high school bordering on the Columbine High School massacre, Todd Haynes' complex I'm Not There (2007), uses non-traditional narrative techniques, intercutting the storylines of the six different Dylan-inspired characters.

More recently, the tradition is carried forward in Roma (2018), by Alfonso Cuarón who deftly talks about his childhood living in 1970's Mexico and the movie is shot in black-and-white.

Photo: Collected

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments