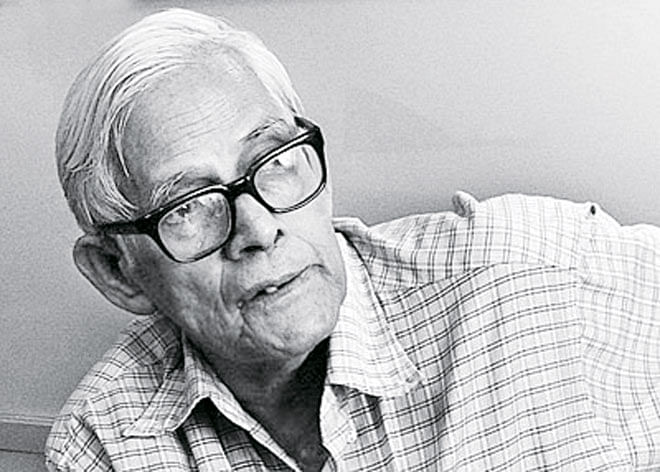

The Great Sardar

The Great Sardar

A fighter, a war hero. A philosopher, teacher, writer, intellectual. Sardar Fazlul Karim adopted all these mantles in an unassuming manner; the labels never seemed to have attracted him, nothing was more important for him than ideals. And he never seemed to have compromised on them. Even when he was forced to spend eleven years in jail in four phases during the Pakistani rule, Sardar was unfazed. He was determined to not let the atrocities of the Pakistani army bring down his spirit to fight and protest, and quietly protested against the torture by participating in the 58-day hunger strike undertaken by political prisoners who demanded humane treatment by jail officials. When such a man argued that you can't ask for revolution but rather welcome it and be a part of it whenever you see a chance, you are bound to take heed and agree with his ideal that revolution is indeed an “everyday affair.”

His was a farmer's family. Born in 1925, the fourth child to his poor but progressive minded parents, Sardar recalled going to the bazaars to sell the produce of his father's farm to traders. “My parents were illiterate and very attached to their roots. It wasn't natural for people like them to send their kids to school. But they did. And that's why I'll forever revere these simple folks and always be indebted to them,” wrote Sardar in his autobiography Ami Sardar Bolchi.

Sardar always referred to himself as a last bencher. He had always been more interested in applying his studies. He read for the pleasure of it, not because he was forced to do so. He never took grades seriously, and it's small wonder that his older brother Monje Ali was skeptical about his results and after his HSC exams asked him in a tone of cynicism about how they went. Sardar's answer was simple, “I think I'll definitely pass.” When his brother asked whether he didn't expect anything more, Sardar in his quintessential unassumingly witty manner quipped, “What else can you do in your exams but pass them?” Without trying too hard, but by just applying all his literary and practical knowledge in his papers, Sardar stood second in his HSC exams, a feat celebrated by his friends and family but barely acknowledged by the great man himself.

It's a well-known fact that Sardar was involved in progressive politics as a student. He had often stated that he saw the communist party as a family and joined it from a sense of idealism at a very young age. But he never saw himself as a party member, didn't even pay any fee to be a registered member but the party always saw him as their own. “Those who had ideals about bringing about a positive change in the society would hesitate before calling themselves members of the communist party. They would often wonder what if they can't struggle and fight for that change. How could they call themselves members of a party that fought for the revolution? Members of the party always believed that no change was possible without uniting the Hindu and Muslim communities and they struggled religiously to unite these two groups. And this commitment to work for the marginalised, the voiceless was probably why this party was known as the people's party,” he has said.

After completing his Masters from Dhaka University, Sardar was appointed as a lecturer of Philosophy in the same institute in 1946 at an age when most people struggle to complete the final laps of their Bachelors. His love for books was not just limited to reading them and spreading the knowledge to his students. He wanted philosophy to be accessible to all and that's probably why he translated the works of great philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, Engels and Rousseau into Bangla. Every problem, every dilemma could be addressed through rational, logical manner. When some students asked him whether Americanism could be seen as a problem, he quietly answered, “Even as you are asking me this question, I can see a look of fear in your eyes. If you could look at this 'Americanism' as a mechanism instead of viewing it with so much fear, then you'd find it easier to think about this issue. What exactly is 'Americanism?' It's a man-made problem and it will continue to exist. [. . .] I can only ask you people to look at life with hope. If you are looking at America as a negative force and yourselves as a positive force, then why are making out the negative to be bigger than the positive?”

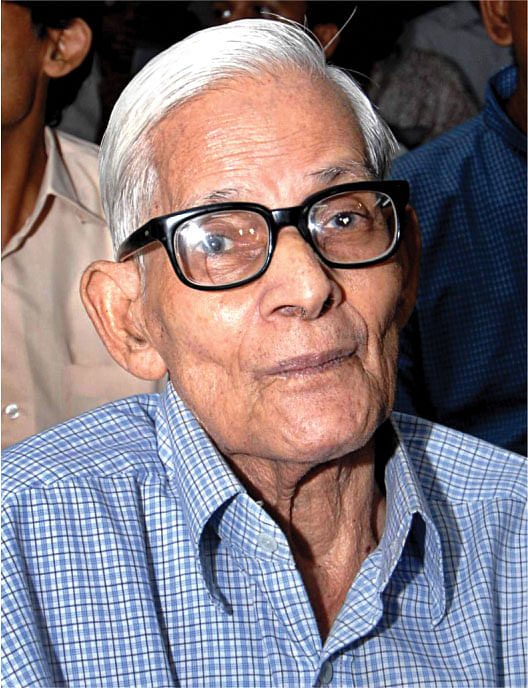

This great man breathed his last on June 15 this year. While we mourn his death and grieve about the great loss to our country, Sardar himself looked at death in his usual simple yet thought provoking manner: “I believe that human beings are truly born on the day they die. You might think that this is all drivel. But think about it. Sheikh Mujib was born on the day that Sheikh Mujib died. The complete portrait of a person is disclosed only after their death. No matter how a person dies, whether succumbing to an illness or dying in war, after their death, the circuit that begins from birth is finally completed.” (Translated from Sardar Fazlul Karim's autobiography Ami Sardar Bolchi.)