The “Ershad Syndrome”

The “Ershad Syndrome”

AS analysts and experts are unanimous in imputing the prevalent chaos, corruption and anarchic violence in Libya, Egypt and Iraq to their former (corrupt) dictators -- Qaddafi, Mubarak and Saddam Hussein -- one wonders as to why Ershad should remain unscathed and untouched for committing similar crimes in Bangladesh. He not only retarded the growth of democracy and civil society in Bangladesh, but also singlehandedly destroyed the social fabric, respect for law and order, and whatever was left of ethical values and piety among the average people in less than nine years of autocracy. We may call Ershad's legacy of crime, corruption, hypocrisy and mendacity as the “Ershad Syndrome.”

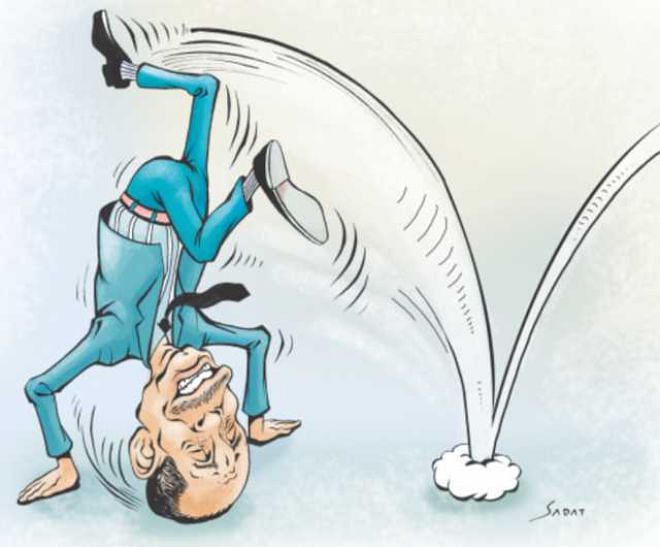

Ershad's Machiavellian modus operandi is at the roots of most evils afflicting the country for the last three decades. In 1988, the late Quamrul Hassan, in the last sketch of his life, titled Desh Aaj Vishwa Behayar Khoppore (our land is now in the hands of the champion of shamelessness), aptly portrayed him as he was at that time. Although Ershad was not the first or only autocratic, corrupt ruler, he was the one to institutionalise corruption, deception, and hypocrisy. His contributions to the degeneration process outweigh those of all the previous and succeeding regimes in the country. He is as deceptive as Bhutto, as dishonest as Marcos, as cruel as Suharto and as hypocritical and “Islam loving” as Ziaul Haq. Although he served only six years for misappropriation of public funds, renowned jurist Dr. Kamal Husain observed soon after his overthrow in 1990, that the dictator deserved at least 500 years for the various crimes he had committed against the people of Bangladesh.

His military takeover in1982 came as a bolt from the blue. It was least expected and totally unnecessary. The country was just recovering from the trauma of the bloody Liberation War and the post-Liberation disasters -- socio-political and economic mismanagement, famine, political assassinations and military rule following the killing of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1975. While the country was crossing the threshold of democracy, Ershad's military intervention was instrumental in turning the country into one of the most corrupt, and what some experts believe, a “failing state.”

Unfortunately, Awami League's top leaders welcomed the military takeover by Ershad in 1982, and later legitimised his autocracy by participating in the so-called parliamentary elections in 1986, along with the Islamo-fascist Jamaat-e-Islami. Preferring Ershad's Jatiya Party to Khaleda Zia's Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), the Awami League joined hands with the former dictator during the second tenure of the BNP-led coalition government in 2001-2006.

Then again, it is unfair to single out Awami League as the only party to have courted Ershad. BNP and Khaleda Zia also wanted him to join the BNP-led Alliance against Awami League's 14-Party-Alliance in 2006. Ershad's refusal led to his two years “conviction” for misappropriation of public funds in 2006. BNP also tried to win over the former dictator's estranged wife Roushan Ershad to forge an electoral alliance against Awami League. Interestingly, many “leftist” leaders and advocates of freedom and democracy, including Moudud Ahmed and Kazi Zafar, were members of the Ershad government in the 1980s.

Ershad was instrumental in de-secularising secular Bangladesh by introducing Islam as the “state religion,” which has marginalised all non-Muslim citizens of the country. This act has also legitimised political Islam for an indefinite period. No government since the overthrow of this dictator in 1990 has succeeded yet in scrapping this clause from the Constitution, which is simply unconstitutional and in violation of the spirit of the Liberation War.

Unfortunately, the “Ershad Syndrome” is full of life and thriving at every level of society in Bangladesh -- from the parliament to the mosque, and from the market place to the bedroom. What was once taboo became an acceptable behaviour. Politicians, renowned intellectuals, well-to-do professionals, “leftist” student leaders, and even “nice and decent,” married and unmarried women -- housewives, singers, newsreaders -- legitimised his dictatorial rule, corruption and profligacy. Neither has the general changed after all these years, nor have his avid followers and comrades-in-arm. One may cite Ershad's and the Awami League government's latest somersaults -- before and after the farcical parliamentary elections of January 5 in this regard. What may surprise any political scientist is that Ershad and his party men are simultaneously part of the government and also of the opposition.

In sum, while the “Ershad Syndrome” is thriving in Bangladesh, Ershad is still the role model of corrupt politicians, traders, professionals and government employees. Thus, there is no room for complacency because of economic growth and rise in the Human Development Index (HDI) in Bangladesh since the 1990s. They are mainly attributable to the private sector and hardworking, poorly paid Bangali workers.

Sustained growth and development are subject to the rule of law and very low incidence of corruption. As Bangladesh witnessed lower growth (which is likely to go down further) during the violent civil-unrest in the last few months, one may guess what can happen to this bubble economy if there is a big disruption in foreign remittance and garment factories, which anarchic rioters love to burn down, as witnessed in the recent past. According to the Foreign Policy magazine, Bangladesh is now potentially one of the ten most volatile countries in the world. Can freedom and democracy loving people and leaders of Bangladesh reverse the process by abandoning the “Ershad Syndrome” forever? It is the most pertinent question today.

The author teaches security studies at the Austin Peay State University at Clarksville, Tennessee.

(This column will henceforth appear on alternate Saturdays)