Tajuddin Ahmed: Our history maker

Tajuddin Ahmed: Our history maker

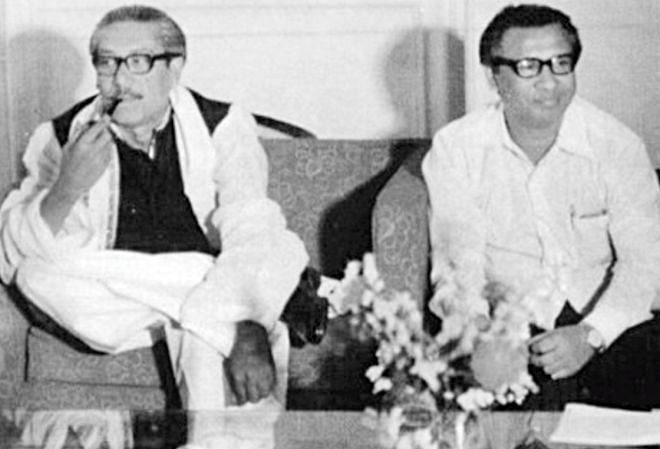

TAJUDDIN Ahmed was a man of history. He understood the nuances of history. He was able to analyse history in all the forensic details that such analyses called for. Of greater importance than all this preoccupation with history on his part was his own role in the making of history. Between 17 April 1971 and 12 January 1972, Tajuddin Ahmed fashioned history. He was, and remains, our history maker. The history he forged in the darkest period of our collective life was ours.

And then the forces of anti-history struck him down.

There was a seer in Tajuddin Ahmed. His was the voice and the resolve which eventually carried us through the War of Liberation in 1971. Had it not been for him --- and do not forget that Bangabandhu had been taken prisoner by the Pakistan army --- the question of liberty for the seventy five million people of Bangladesh would easily have run into a wall. Or gone downhill, to hit rock bottom. In the minutes before the Pakistanis cracked down on unsuspecting, unarmed Bengalis on 25 March 1971, Tajuddin Ahmed tried persuading Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to leave the city. That, thought Tajuddin, would make it easier for Bengalis to go into a war of national liberation. Bangabandhu had his own and very credible reasons, of course, not to leave the scene despite the attendant risks. The elected leader of a majority party in parliament does not run from danger. Bangabandhu chose to stay and confront the world on his terms. For his part, Tajuddin chose his own path. He would give shape to a government, the very first in Bengali history, and win a war against a formidable military machine.

A remembrance of Tajuddin Ahmed is surely the role he played in weaving the Mujibnagar government into a credible pattern in April 1971. He it was who undertook the task of locating all the senior leaders of the Awami League then making their way across the frontier into India in the face of all-round genocide and bringing them together as a wartime administration. There were those who clearly felt uneasy about Tajuddin's playing the foremost role in organizing the war; and they went overboard in trying to push him aside. Lawmakers elected on the Awami League ticket at the December 1970 elections were made to gather, the sole objective being a removal of Tajuddin from the leadership of the movement. Tajuddin did not waver in his overriding goal of seeing the nation through to victory. He survived, to wage war in Bangabandhu's name. On 16 December 1971, Tajuddin Ahmed's place in history was firmly etched in the human consciousness.

There was, in Tajuddin, a proper man of principles. His diaries, dating from the late 1940s, are but a window to the thought processes working in him even at that young age. In the early 1970s, as Bangladesh's first finance minister, Tajuddin's understanding of the priorities before the nation was without ambiguity. Alone in the cabinet, he believed that Bangladesh's future lay in its use of its human resources. A nation which had gone to war and come back home in triumph could achieve greater wonders. Hence there was little need for the World Bank, for the IMF, indeed for aid from the capitalistic West. He felt it was pointless to speak to Robert McNamara in Delhi in February 1972. And yet, in 1974, when he did see McNamara in Washington, he must have felt the irony of it all. The government he was part of had changed gear, toward the West. He had not. Disillusion had taken over. Only weeks later, he would be out of government. His leader, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, would ask him to resign. The decent man that he was, Tajuddin quietly stepped aside.

The extent to which Tajuddin Ahmed mattered in Bengali politics was made obvious to a group of young economists cheerfully explaining the details of a proposed Six Point plan on regional autonomy to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1965. The venue, as a participant at the moonlight-dappled meeting once told this writer, was a boat on the Sitalakhya, away from the prying eyes of Ayub Khan's intelligence. Bangabandhu was satisfied with the economists' analysis of the Six Points. And then Tajuddin took over, with question after question. The young economists, until then focused on Mujib, knew at that point that the Awami League had a formidable presence in Tajuddin's intellectual persona. Tajuddin's political and intellectual brilliance was a matter of worry for Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. When, soon after the elections in 1970, President Yahya Khan prepared to visit Dhaka, Bhutto told him to watch out for Tajuddin, for Tajuddin asked the questions and demanded the answers. After all, Bhutto had reason to know. In early 1966, when as Ayub Khan's foreign minister he had challenged Mujib to a debate over the Six Points at the Paltan Maidan, it was Tajuddin who chose accept the challenge on behalf of his leader. In the event, Bhutto did not turn up.

Tajuddin Ahmed brooked no nonsense. He tolerated no sycophancy. And he was not squeamish about making his thoughts on politics public, loud enough for everyone to hear. In spring 1974, he warned of looming danger: those who argued that Bangabandhu ought to have more powers were only planning to isolate him from the masses. An isolated man, he told his party men, was a lonely man. And a lonely man could easily be pushed aside. That was Tajuddin, nine months before January 1975.

Tajuddin's belief in socialism never wavered. But socialism, he made it clear to people impatient for results, was a matter of dedication. It was a plant which needed ceaseless nurturing. Socialism was much more than an idea. It was, he repeated over and over again, underpinned by faith. Hypocrisy had no place in the socialist's concept of the world.

In August 1975, as he made his way out of his home and to prison, he knew he would never return alive. On 3 November, when the assassins brought him and his three colleagues together at Dhaka central jail, he had little illusion that those men were there to kill. And kill they did.

Bangladesh crumbled to its knees on the day Bangabandhu died. It was paralysed when Tajuddin Ahmed was gunned down with his Mujibnagar colleagues three months later.

(Tajuddin Ahmed, prime minister in Bangladesh's government-in-exile in 1971, was born on 23 July 1925. He was murdered in prison on 3 November 1975).

The writer is Executive Editor, The Daily Star.

E-mail: ahsan.syedbadrul@gmail.com