Silenced by salinity

Silenced by salinity

Rising salt content damages croplands forcing farmers to change livelihood

More than a decade ago, Muroti Halder, now 50, used to have a hectic schedule at this time of winter.

Fresh harvest of Aman paddy used to arrive at their yard and Muroti and her family members had to remain busy in threshing, boiling and sun-drying the paddy.

The entire area was full of activities. Aroma of the newly harvested paddy used to fill the air.

These are only beautiful memories now.

For the last several years, Muroti's family and their neighbours in Keyabunia village, six kilometres away from the southwestern seaport town of Mongla, cannot grow rice on their land due to rising salinity.

A fall in freshwater flow from the upstream, rising sea level, shrimp cultivation and its uncontrolled expansion, and congestion in canals for embankments built by politically influential people are mainly responsible for salinity in Mongla and other southwestern coastal areas.

A fall in freshwater flow from the upstream, rising sea level, shrimp cultivation and its uncontrolled expansion, and congestion in canals for embankments built by politically influential people are mainly responsible for salinity in Mongla and other southwestern coastal areas.

Now almost the entire year, land and canals are used mainly for farming brackish water shrimp that is exported to Europe and the US.

As a result, Muroti's family, now being fed by her 32-year-old son Washington Halder, has to buy all the rice for a year from the market.

People in her village and most other localities under Mongla upazila of Bagerhat now have to depend on the market for rice though paddy cultivation was once their livelihood.

Similar is the story for people in parts of Rampal upazila of the same district, and some areas of Shyamnagar upazila of Satkhira.

Rising salinity has taken a toll on crop production and thus turned these southwestern coastal areas into a food buying zone, according to locals and crop acreage figures of the government.

"Even a decade ago, rice grown on our land was enough to meet all the needs of our family. We also had surplus rice," said Muroti, sitting in front of their wooden house. They used to yield 200-300 maunds of paddy a year.

Just beside her house, several-acre low-lying land was seen submerged in saline water -- no crops, no green shoots. The land is for shrimp farming.

In the past, people in these coastal areas depended largely on transplanted Aman rice to ensure the supply of their staple food. And during the early years of shrimp cultivation, farmers cultivated both rice and shrimp on their fields.

But over the years, Aman acreage fell gradually due to rising salt content in soil, resulting mainly from continued saline water retention on farmland for shrimp cultivation and congestion in canals.

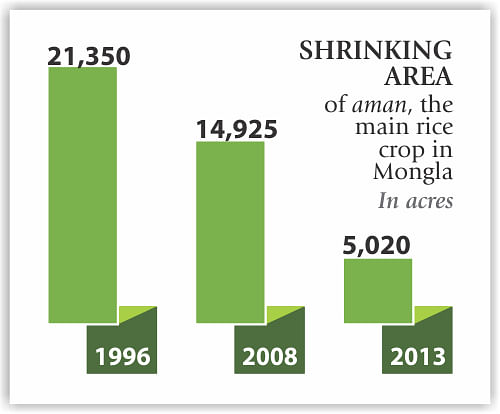

In Mongla upazila, Aman crop area fell 30 percent to 14,925 acres in 2008 from 21,350 acres in 1996, according to Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

As a result, rice production in the area fell and so did cropping intensity.

During fiscal 2013-14, Aman area was 5,020 acres and 6,277 tonnes of rice was produced. The Mongla upazila records the annual demand for foodgrain at 27,286 tonnes.

Officials and locals said crop production and acreage fell drastically due to increased salinity after the cyclone Aila in 2009.

In case of Rampal, Aman area plunged 33 percent to 22,815 acres in 2008 from 34,010 acres twelve years ago, according to the BBS.

"We stopped cultivating rice fifteen years ago as the yield was very poor due to salinity," said Romen Mandal, a resident at Chandpai union under Mongla upazila.

Mohammad Abdul Halim, a small farmer at Shyamnagar upazila of Satkhira, said once rice could be grown on all croplands in their union. Now the acreage has come down to one-fourth due to salinity, he said, adding that five out of 12 unions under Shyamnagar suffer the same fate.

"My tension rises when rice prices go up," he said.

Abdullah Al Mamun, agriculture officer of Mongla upazila, admitted that the coastal area has turned into a food-deficit region. "People have become market-dependent," he said.

"Salinity is a curse. Aus and Boro rice cannot be grown here, while Aman cultivation also faces setback. None of the varieties can tolerate such a high level of salinity."

Cultivable land has come down drastically due to salinity, he added.

More than two lakh hectares of land in the south have lost potential for agriculture due to increasing salt content over the past four decades, according to Soil Resource Development Institute (SRDI) of the government.

SRDI data shows that the level of salinity in these areas ranges from 12 dS/m to more than 16 dS/m (deci Siemens per metre, a unit for measuring salinity).

Soil scientists and water experts had earlier told this correspondent that such a high level of salinity is beyond the tolerable limits of rice, majority varieties of which survive and thrive below 4 dS/m.

"Plants cannot absorb sufficient amount of water due to high salt concentration. In this situation, plants actually die from water stress or drought in most soil if the soluble salt concentration is high," according to Southern Master Plan for Agricultural Development.

"Plants also suffer from toxicities of specific salt and nutritional imbalances."

The master plan was jointly launched by the agriculture ministry and the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation last year.

To ensure food security, many farmers in these coastal areas -- Mongla and Rampal -- tried to grow saline-tolerant rice during the Boro season in recent years.

But the level of salinity in the soil was so high that even these stress-tolerant and improved varieties, released by agricultural research institutes, did not prove profitable for growers, farmers and agriculture officials said.

Mamun, citing some farmers in Mongla upazila, said: "Experiences were not good."

Not only rice farming, trees such as betel nuts and coconuts as well as livestock also take the blow of rising salinity.

CHANGES IN LIVELIHOODS

Now the main livelihood of Muroti's family and others in the southwestern coastal belt is shrimp cultivation.

Her family began shrimp cultivation in 1995 and gradually expanded area. Today, her son Washington Halder cultivates brackish water shrimp on all the 14 acres (5.66 hectares) of their cropland.

Official data shows shrimp cultivation has grown over the years due to a rising export demand, government's policy support and financing by multilateral lenders such as World Bank.

The area under shrimp farming was 55,312 hectares in 1984 and rose to 2.75 lakh hectares in fiscal 2012-13, according to the BBS and the Department of Fisheries.

Washington said they earn Tk 4 lakh a year from shrimp farming, better than what they would get from rice cultivation.

But salinity did not impact rice cultivation only; it also affected livestock, vegetables and fruits. So given all the losses, shrimp cultivation is not as profitable as rice farming, said Washington, one of the 8.33 lakh shrimp farmers, who help bring more than $500 million from shrimp exports a year.

However, income varies from one year to another due to disease attacks on shrimp farms and price fluctuations in the global market.

Shrimp farmers in the locality said frequency of disease attacks has risen in recent years. Prices also went down of late.

During the early days of shrimp farming, Washington Halder and his neighbours were excited as incomes were better and investment was low.

Romen Mandal, who has 1.3 acres of land, said disease attacks on shrimp farms are now a major concern.

"Many of us harvest shrimp early to avoid losses. Our harvests have almost halved," he said.

Washington said he follows suggestions of fisheries officials to ensure a good harvest. Even after that, he incurs losses due to outbreak of diseases.

"But as I grow shrimp on my own land, it does not affect me much. But those who grow shrimp on leased land really fall in trouble."

Mohammad Shah Alam Sheikh, a shrimp farmer at Chandpai union under Mongla, said planned farming provides higher benefit to growers.

Their incomes also depend largely on the prices of shrimp in the global market, he said.

After reduced earnings in fiscal 2012-13, shrimp growers fetched higher incomes the following year as exports soared.

Shrimp exports again slipped 4.55 percent year-on-year to $276 million in July-November this fiscal year, according to Export Promotion Bureau.

As demand fell, prices of shrimp also declined in recent months -- to Tk 350-Tk 400 each kilogram (40 pieces) now, from Tk 700-Tk 800 in June last year, Sheikh said.

"We all, from big to small farmers, are incurring losses because of the fall in prices," he said. "Our wellbeing is now linked with disease attacks on farms and prices on the international markets."

As a cushion against these adversities, many shrimp growers in the coastal region have started cultivating carp and tilapia fishes along with shrimp. Some switched to crab farming.

Washington Halder has been growing carp for the last several years, especially during monsoon when salinity subsides.

"We get at best five to six months to cultivate these fishes. We have to harvest them before the rise of salinity in March-April," he said.

But it would be better if he could grow carp throughout the year, along with rice, he said. "Once, we grew rice and fish, including shrimp, together. We also could rear cows.

“It's unfortunate that we have croplands but we cannot grow our staple food."