See the Sea

See the Sea

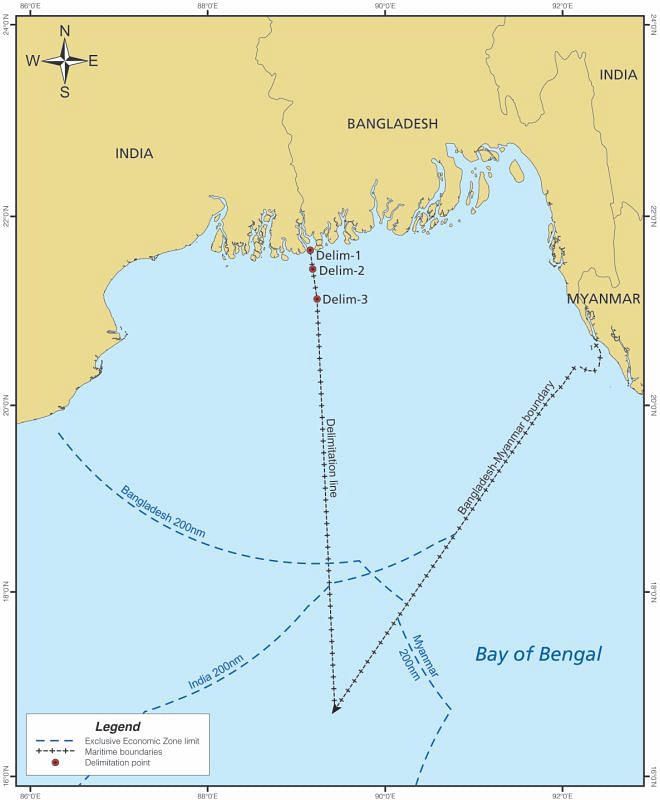

THE settlement of longstanding maritime boundary dispute between India and Bangladesh ushers a new horizon in the bilateral relationship between the two countries. Both the countries have hailed the findings of the Arbitral Tribunal and indicated their willingness to comply with the outcome. The Hague based Tribunal constituted under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) on 7 July 2014 awards 4/5th of the disputed sea zones in favour of Bangladesh(19,467 sq/km). The decision saves Bangladesh from being a sea locked country by Myanmar and India from both the sides. The award, not to mention, bears huge implications in many dimensions. In this write up, I will discuss the main attributes of the award and then proceed to focus on some implications of the decision from international and national viewpoints.

One of the fundamental points of the dispute was to determine the land boundary terminus. This was necessary in order to locate the mid-point of land boundary from which the equidistance line for maritime boundary delimitation is usually drawn. This issue also draws huge attention as it proves to be a decisive factor on the question of ownership of the much-talked about South-Talpatty/New Moore Island. In order to decide the question it was necessary to trace the main-channel of the border river Hariavanga. If it flows along the western side of the Island, it belongs to Bangladesh. But if it flows along the eastern side of the island it belongs to India. India establishes that the midstream channel of the Hariavanga River is located on the eastern side of the submerged South-Talpatty Island. India relies on the Radcliffe Map and its interpretation.

In absence of any recent map, Bangladesh has to rely on an earlier survey to establish the claim which the tribunal considers less authentic. However, it appears that the ownership issue of the island as such was not actively in the mind of the parties and the Tribunal itself. Specially, it appears that Bangladesh was less interested to advance further arguments on the point once it failed to show the existence of the island in its recent map. For this reason, Bangladesh opposed India's proposition to make any base-points counting South Talpatty as a 'low-tide-elevation'. As per Bangladesh, the Island is a 'minor geographical feature' and is 'far too insignificant and its stability far too suspect' in attaching importance to delimitation consideration. India, however, raises the plea of 'universal practice' to select base points from low-tide elevation like the South Talpatty Island. The Tribunal disapproves the Indian contention. Thus, it is seen that Bangladesh has not suffered to the extent as was anticipated on the South Talpatty question.

The second most important issue the case involves is the interpretation of 'special circumstances' under Article 15 of the UNCLOS. India argues for applying 'equidistance' method. Interestingly, India does not deny the significance of any 'special circumstances' in delimiting maritime boundary but submits that in the instant case there are no relevant circumstances as such. Bangladesh, however, argues that the coastal instability, concavity of the Bangladesh sea coast, economic dependence of the people on sea resources should be considered as 'special circumstances'. The Tribunal accepts only the concavity of the coast as a 'special circumstance' and adjusts the boundary line in a justified manner. The Tribunal considers that the equidistance approach provides 'no redress to Bangladesh from the cut-off resulting from the concavity of its coast and cannot be accepted for this reason'. In taking this approach, the Tribunal notes from the Bangladesh-Myanmar case of 2012: “having considered the concavity of the Bangladesh coast to be a relevant circumstance for the purpose of delimiting the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf within 200 nm, the Tribunal finds that this relevant circumstance has a continuing effect beyond.” This adjustment allows the coasts of the Parties to produce their effects, in terms of maritime entitlements, in a reasonable and mutually balanced way.

Apart from the two points discussed above, the Tribunal makes length discussion on the question of 'angle-bisect' principle and the theory of 'natural prolongation' of the continental shelf advocated by Bangladesh. But ultimately it appears that the 'concavity' principle has been decisive in reaching to a satisfactory conclusion. Thus, the Tribunal finds an equitable solution in establishing the parties' right over the territorial sea, exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf and beyond of the Bay of Bengal.

The implications of the award are far reaching. Firstly, it will now facilitate Bangladesh's ability to economically exploit the waters in the Bay of Bengal. Bangladesh, now, will have greater leeway to explore for oil and other natural resources in the once-disputed waters, opening up a potential economic boon for the country.

Secondly, it will unfold the other locks of bi-lateral diplomacy between India and Bangladesh. The two countries may now concentrate on the land boundary and enclave issues. The Arbitral Tribunal itself notes in one of the places of its award: “maritime delimitations, like land boundaries, must be stable and definitive to ensure a peaceful relationship between the States concerned in the long term. In general, when two countries establish a frontier between them, one of the primary objects is to achieve stability and finality. The same consideration applies to maritime boundaries.”

Thirdly, the peaceful settlement itself is an indication of the success of the UNCLOS III dispute settlement mechanism. On one hand, the Tribunal have fashioned the law of the sea jurisprudence in a more coherent manner, on the other hand, the Bangladesh-India approach will be a learning ground for other jurisdictions having conflicting maritime claims. To quote, Paul Reichler, one of the Counsels for Bangladesh in the arbitration: “it continues the progressive development of maritime delimitation jurisprudence in a positive direction. Bangladesh was not the only winner today. With its careful and balanced decision, the arbitral tribunal brought great credit to itself and showed once again the wisdom of the drafters of UNCLOS in providing for compulsory dispute settlement.”

Fourthly and lastly, Bangladesh will be able to review its own ocean policies, legislation and strategies in the light of this achievement. This will also put Bangladesh to assess its past state initiatives about the Bay of Bengal and encourage forging a regional sea management plan on the basis of geo-politics. Entering into good sea exploration treaty, creation of sea research institutions and establishment of ocean governance institutions are the urge of the time. Bangladesh now should be able to see the sea from a wider angle.

The writer is Assistant Professor of Law, Jagannath University, Dhaka. He is currently on study leave to pursue his PhD in law at the Victoria University of Wellington.