Partly nostalgia, partly agony…

Partly nostalgia, partly agony…

Tusar Talukder strolls through a poet's world

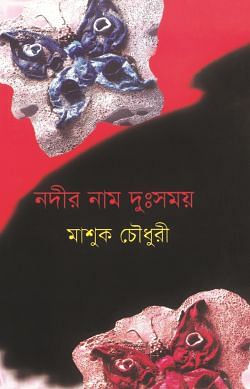

Mashuk Chowdhury,

Shahosh Publications

TWO or three years back, I was intensely engrossed with the poetry of some contemporary young poets such as Obayed Akash, Binoy Barman, Mujib Erom and so on. Consequently I reviewed several books by some of them. Truly speaking, I got attracted to our contemporary short stories as well Latin American literature. Sometime ago, I came by a collection of poetry, Nodir Nam Dushshomoy, by Mashuk Chowdhury.

Allow me to jot down some words regarding Mashuk Chowdhury. A poet of the 1970s, he invariably tries to keep himself far away from our known poets' circles. Which is why very few of us have had the opportunity to get acquainted with his poetry. My opinion, if Wordsworth is right in defining poetry as a 'spontaneous overflow of feelings', is that Mashuk Chowdhury has rightly captured that feeling. Of late, it has been my habit, whether it is good or bad I do not know, to hand over any newly got copy of a book to one of my elder brothers, R. K. Saha, a sheer literature lover. In the matter of reviewing this book, his opinions also helped me stay on the proper track.

Surprisingly enough, I went through almost all the poems of the collection in one sitting. At the outset, the composition, 'Pherar Train Nei' (No Train to Return) portrays the days the poet left behind, bearing a nostalgic tone. I can assure you that many of us can relate to the tales of the poem. The poem encapsulates the poet like a train passing through the golden time of his life. And now he is living in an age of destruction. He believes time has thrown him into the chaos of this human civilization. Bad times come to the poet like a big question mark because he deeply feels there is no train left to go back from this terrible age. Thereupon he finds the present age enervating. The next poem, 'Dusomoy' (Bad Time) carries the essence of the preceding poem. Here the poet argues that as the days go by, the darkness of the human mind is getting deeper and deeper. This composition also projects the idea that lyricism has evaporated from modern poetry like the decaying nature of women's beauty. The poet laments this irreparable loss. Now 'poetry' has become synonymous with 'antipathy'. To clarify the matter, Mashuk Chowdhury has the following lines:

“Poetry can be attacked and avoided

But it cannot ne demolished”

The lines conspicuously inform us of the poet's belief in the imperishability of poetry. Apart from, this notion of Mashuk is somehow similar to the belief of William Shakespeare regarding poetry. Mashuk also reminds us that a poet is committed to none; he/she is only committed to history and civilization. Nobody can share the happiness as well as the sorrows of a poet. His/her feelings are only stocked for himself/herself.

In 'Dusomoy' (Bad Time), the poet engages himself in a debate about who is a poet or who is not. In other words, what the responsibility a poet must have or must not have is the most talked about issue of the poem. Poems like 'Smritir Shohor' and 'Gochhito Smriti' are packed with nostalgic tones. Again, the poem entitled 'Shishoswargo' (Heaven of Children) provides us with an idea of the utopian state which will be governed only by children. A child will be given the charge of prime minister. The poem allegorically focuses on the safety of children. The rights of children will be strictly implemented in that state. The state will guarantee the security of life for all children, even their right of vote. By the same token, 'Kobitar Sangbidhan' (Charter of Poetry) declares that there is no word like 'forbidden' in the constitution of poetry. Poetry is free, untamed and wild. To

decipher the idea, the poet here utters the following lines:

“Like a freedom fighter I alone am enough

To protect pure love”

The book ends with 'Life goes on and on', informing us that only love can make a bridge among people. The end-note takes one aback.

“People, deeply prone to love

Repeatedly coming to the temple of love

Got satisfied,

With a thought of a token-less existence of immortality”

Overall, the book comprises of three parts. The beginning poems unfold the nostalgic thoughts of the poet, the middle part depicts his lamentation at not getting his desired universe and the concluding phase exposes the underlying strength of love.

Tusar Talukder is a free lance writer and translator. He teaches English at Central Women's University (CWU). He can be reached at tusar.talukder@gmail.com