English in Malaysia and Singapore

English in Malaysia and Singapore

The young editors of a student magazine, The New Cauldron (1949-60), the official organ of the Raffles Society of the University of Malaya in Singapore, in their youthful idealism and unflagging optimism, wrote in their editorial column, “National Unity,” for the Trinity Term issue of 1949-1950:

Professor T.H. Silcock, in his pamphlet 'Dilemma in Malaya', says that 'Self-government implies a self to do the governing, and it is our responsibility to bring that self into existence.' Before that 'self' can emerge we must have a solidified concoction of all the socially, economically, politically and culturally disunited peoples in Malaya. Can we achieve that solidarity? Assuredly we can. The process of transforming different peoples with diverse ideas into a single unit may take a few decades but ultimate unity is ours.

The rest of the editorial is devoted to articulating the principles that would enable the emerging nation to attain the desired unity: equality of races and equal citizenship for all, for “There is no room for discrimination in a ship upon turbulent waves of suspicion”; undivided loyalty to Malaya, particularly by members of the migrant races and, finally, the evolution of a common language. On the subject of language, the starry-eyed editors further wrote, in their editorial article, “The Way to Nationhood,” for the Hilary Term issue of 1949-1950:

The people of Malaya are a mixed crowd, but they possess most of the requisites for nationhood. Time must be given for a common language to be evolved. This will come about through increased contact between the different communities. A Malayan language will arise out of contributions these communities will make to the linguistic melting pot. The emerging language will then have to wait for a literary genius who will give it a voice and a soul, a service which Dante performed for the Italian language.

It is important to begin this article by quoting from these young writers at length because they were some of the “pioneers” of what was then a nascent Malayan literary tradition in English, and what is now acknowledged as modern Malaysian and Singaporean English language literary tradition. In their vigour, vibrancy and valour, these writers embodied the imagination and spirit of all fellow writers in the medium, and even perhaps of their entire generation. The writers were talking about self-determination, self-governing, solidarity, forging of a common language and creating a united and unified nation. But which nation did they have in mind? They were all living in Singapore as students of the only university of the colony, University of Malaya, established in Singapore in 1949, the year these magazines and editorials were published. They must have been aware that Singapore was no longer part of British Malaya at the time, as it had been separated from the rest of the Federation which was established with eleven of the other Malayan states in 1948. The writers would have also been aware that equal citizenship and the possibility of creating a new language for establishing unity and solidarity between the diverse races in the emerging Malayan nation were far from the reality.

In 1957 Malaya was given independence, but Singapore still remained a Crown Colony and continued to tread a separate path. In the Merdeka or Independence Constitution, bahasa was accorded the status of national language, although it was agreed that for the first ten years “Chinese, Tamil and English could continue to be used as working languages with the position to be reviewed thereafter.”A provision was, however, also introduced in the Constitution that stated that after ten years Malay would be the country's sole official language.

Singapore was allowed self-government in 1958 and, later, independence in 1963.

Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore joined the Federation of Malaya and formed the new Federation of Malaysia on 16 September 1963. This merger between Singapore and Malaysia, after a period of separation, came to be seen in some quarters as “a marriage of equals” and “happy marriage.” But the happy marriage soon turned sour as differences between the Singapore Government led by Lee and the Federal Government became irreconcilable.

Singapore emerged as a sovereign nation on 9 August 1965.

A Tradition with Two Tributaries

I have given a synopsis of the turbulent political events from 1946 to 1965 to enable readers, especially those who are not familiar with the history of colonial Malaya and later Malaysia and Singapore, to appreciate the geopolitical milieu in which the tradition of English writing began, and continued to develop, in the two countries, first as one and then as two tributaries stemming from the same source. It was initiated by a coterie of writers, who were young, English-educated, undergraduate students at the University of Malaya, mostly coming from a middle-class, and many of them from a migrant, background. They were working under a unique set of circumstances and mainly sailing against the current. They began writing when the whole country was in a ferment, with clashing ideologies and competing visions of the nation creating such an explosive environment that their homeland eventually could not hold together, and gave birth to two sovereign nations. They were Malayans and yet they chose to write in an “alien” language, a language that the colonisers had used to execute their imperial licence and to subjugate their fellow people body and soul. The editorial of The New Cauldron, for the Michaelmas Term of 1955, argued:

We have assessed previous undergraduate attempts at the creation of an artificial language by an arbitrary mixture of phrases drawn from the existing languages spoken in Malaya. We regret to say that this language, Engmalchin [acronym for English, Malay, Chinese and Indian], as its advocates termed it, is a failure if only because of its self-conscious artificiality and the failures of its 'sires' to understand that language can never be created by edict…. The crisis lies in the lack of a common cultural tradition out of which artists can draw their inspiration and which can serve as a common pool of references. Once this is found, however shallow it may be, the language problem vanishes. So long as we understand and appreciate the same values and 'monuments of unaging intellect' the languages in which these values and monuments are expressed do not matter.

The Penang Writers circle, in their manifesto of 1969, also expressed a similar view of creating a new national identity by synthesising the values of the different races and creating a set of common values, which would be inclusive and reflective of the practices of all Malayan people:

It is the imperative duty of our writers to reflect deeply the rich and varied life of our multinational people, help to pose correctly the multifold problems confronting our young nation and create a rich modern literature that reflects our national identity… so that out of the plethora of our traditions and customs it is possible to distil the essence of the uncreated conscience of our peoples.

The writers chose English as their vehicle mainly from an “unassailable logic” (Achebe's phrase) of convenience. Being English educated, they had no choice but to use English to verbalise their imagination. They had no express political objective behind their choice of medium. In a recent interview with me, the father-figure of Singapore literature, Edwin Thumboo, explained:

The point is that all this [childhood memories] was increasingly stored and recalled in English. English was the only language in which I had some strength. As time went by, Teochew was used less and the little Malay I had, receded. Meanwhile English grew, systematically, daily, as my world grew. If I wrote poetry, and I wanted to, it had to be in English; there was no alternative. As I have said more than once, poets do not choose their language; the language chooses them.

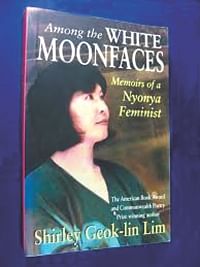

Earlier, EeTiang Hong made the same point in an interview with Kirpal Singh: “One writes in the language one is most confident in.” But although they came to choose their medium from a personal necessity rather than from any political reason, English being their only medium of expression, a medium on which their world, imagination and creativity depended, one without which they could look neither backwards nor forwards nor “seize the day,” obviously they came to love it dearly and become deeply passionate about it. Shirley Geok-lin Lim's poem, “Lament,” captures this sentiment succinctly and powerfully:

I have been faithful

Only to you,

My language. I choose you

Before country,

… before

Lover and husband,

Yes, if need be,

Before child in arms,

Before history and all

It makes, belonging,

Rest in the soil,

Although everyone knows

You are not mine.

They wink knowingly

At my stupidity –

I, stranger, foreigner,

Claiming rights to

What I have no right –

Sacrifice, tongue

Broken by fear.

Lim's poem shows the depth of her commitment to the English language, her sole vehicle for creativity, which she places above country, lover, husband and child. But the poem also exposes a problem which is endemic to all non-native writers of the language, i.e. they are “strangers” and “foreigners” to it; English is but their second or “father” tongue; and, to make matters worse, it was the language used for formulating the axioms of imperialism.

The writers were alert to this issue from the outset and tried to find a suitable solution to it, one that would be acceptable to their inner, writerly selves, as well as to their larger community. They found themselves in a double bind in that they were trying to restore freedom from the colonial rule, redeem their people and cultures from dehumanising oppression of the British, and yet they were using the same coloniser's language to express and articulate their imagination. They were vexed by the fact that their creative medium had its roots elsewhere, and being Malayans they could not draw on the resources of that other culture; Malaya was outside the orbit of Anglo-European cultures, so the only way they could use the language and yet put the agonies associated with it to rest was to detach the language from its source culture and transplant it in the local soil. Only by infusing “local blood,” local verve, local colour and local spirit into the language, could they make it their own; by transforming, modifying and readjusting it to the local context could they make it “bear the weight and texture of a different experience” (Achebe's words). They had to look both inward and outward to achieve this formidable goal. They had to baptise the language in the pool of their personal imagination, rhythm and idiosyncrasy so that the language could revitalise itself, and through a process of gestation, mutation and refashioning, develop into an idiolect. In addition to “personalising” the language, they had to look outward to make sure that they were using the speech that was about them; the speech that was being used by the local people on the street, in the market place, or in their daily business; a speech that they were familiar with from their surroundings, and not from the poets and writers or textbooks that they would have read.

This was, however, not an easy task as there was no local tradition to emulate and writers were basically brought up on English literature. Their main inspiration came from Eliot, Yeats, Dylan Thomas, or earlier writers such as Shakespeare, Donne, Wordsworth, Keats, Dickens, Hardy, Austen or Hawthorne. So how could they suddenly break away from that and create a new aesthetic taste more attuned to the local culture? Their problem was compounded by the fact that there was no one culture in their society but many cultures. They could have benefited from their respective ethnic cultures, Indian, Chinese, or Malay, each of which had a long and resourceful past, but this was not possible as there was nothing common between their medium and their different inherited traditions to establish a continuity. Therefore, to rise above imitative writing and to step out of the shadows of the literary “masters” proved to be excruciating. It required the writer to find the right synergy between the different forces at work in his/her writing, which was a matter of personal talent, confidence and experience. It is because of this, that when the tradition began and started growing, it was mostly confined to poetry. Poetry being intense, intrinsic and economical is dependent on the depth and ingenuity of the individual writer. But fiction and drama being more intricate and extrinsic, dealing with subject-matters that are larger than the self of the individual writer and his/her personal feelings, where s/he has to invent characters having unique shades and attributes as well as plots with multiple layers and multitudinous possibilities, are more difficult to construct or compose. Therefore, it took about twenty years or so for drama and fiction to emerge in the Malaysian-Singaporean tradition of writing from the time of its inception.

However, before literature could fully branch out into the different genres of fiction and drama, a sea change occurred in the literary scene with drastic developments in the political realm. In 1965 Malaysia and Singapore chose to tread different paths owing to intractable and irreconcilable differences on statecraft and nation building by the party leadership on two sides. The Causeway, which stood across the Straits of Johor and acted as a symbol of unity, immediately became a symbol of separation and political sovereignty of the two nations. All the apparatus of the state was put in place to control the movement of people and commodity. This meant literature which was hitherto seen as belonging to one fabric was suddenly split into two, with each having to traverse its own separate track.

Mohammad A. Quayum, Ph.D, is Professor, Department of English Language and Literature, Human Sciences Division, International Islamic University, Kuala Lumpur. This article is the first part of a comprehensive study of literature in the English language in Malaysia and Singapore. It has been edited to a certain extent.