Democracy at its best

Democracy at its best

Scotland has been divided over its referendum for independence. The final hours of campaigning ahead of the referendum have been marked by anger and recrimination.

Amid the rallying cries and emotional pleas – with both Gordon Brown and David Cameron given strong speeches – there has been poison, pure and simple.

The Labour leader, Ed Miliband, has been jostled and heckled; Alistair Darling, the leader of the Better Together campaign, has been “menaced”; thousands of Nationalists demonstrated outside the BBC's headquarters in Glasgow on Sunday and hundreds of campaign boards have been daubed with offensive graffiti or destroyed. And there has been a lot of fib telling, too. All very regrettable, but the Scottish referendum campaign is the democratic process at its most intense.

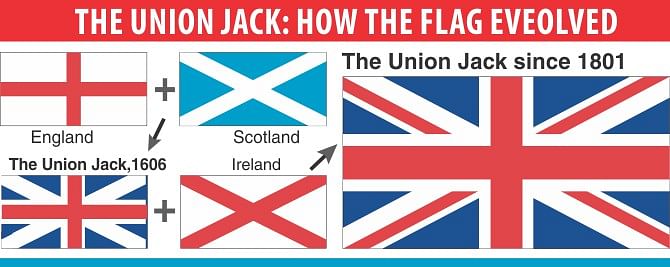

Indeed if Scotland votes for independence, it will have been British democracy's last great show. Britain has been a joint English and Scottish venture since the Act of Union in 1707.

Indeed the 1707 agreement itself was fully 'democratic' by the standards of the day. Neither country had been conquered; it was an agreement freely entered into. The negotiations took place between commissioners representing the parliaments of the two countries. Then both parliaments passed the necessary legislation.

One way of illustrating that democracy has been an Anglo-Scottish achievement is to look at the backgrounds of successive prime ministers. Since 1707 there have been twelve premiers who were either Scots-born or of Scottish extraction – Bute, Aberdeen, Gladstone, Rosebery, Balfour, Campbell-Bannerman, Bonar Law, Ramsay MacDonald, Macmillan, Alec Douglas-Home, Blair and Brown.

Again the process of dissolving the union, if that is what is decided, would have started with acts of parliament. The Scottish draft Referendum bill was even made subject to consultation when it was published in February 2010, a process not copied in Westminster. Then the UK Government drafted an Order in Council granting the Scottish parliament the necessary powers to hold an independence referendum. The draft Order was approved by resolutions of both Houses of parliament. In the Scottish parliament the relevant bill was passed in November 2013. In other words the campaign for independence has been an entirely legal process.

The result is that the turnout of voters is likely to be remarkably high. Already the number of those registered stands at an all-time record: nearly 97 per cent (4.29 million) of the total population aged 16 and over. Moreover, some 90 per cent of those polled in recent surveys indicated that they're 'absolutely certain' that they'll be voting. And this high proportion of likely voters scarcely varies between age groups or between occupational classes. If that is not democracy at its finest, I don't know what is.

For this reason, the way the Scottish referendum has been conducted will be enormously influential around the world, whatever its outcome. If the process can be carried out legally, more or less peacefully and with maximum participation by the citizens concerned, as it has been in Scotland, why should not the Catalans, or the Basques, or the Bretons or the Corsicans, or the Flemings or even the Venetians with their proud history as an independent republic, also put their hopes to the test?