1971 Bhitore Bahire

1971 Bhitore Bahire

Shahriar Feroze reviews the most talked about book of the town…

The publication of the book, “1971: bhitore and bahire (in and out)” authored by A.K.Khandker has created an unanticipated clamour rarely experienced before. Your reviewer thinks the book requires meticulous reading to be judged as treasure or trash. Deciding to review it isn't only because of the ongoing hue and cry, but also to present our readers with a detailed assessment. So let's begin.

The first chapter begins with the political developments that had occurred during the run-up to the military crackdown of March 26, 1971. During that time the author was serving as Pakistan Air force's (PAF) senior most Bengali officer stationed at the Dhaka base, spearheading its administration wing. It outlines the socio-political background of the people of a country that was about to experience war soon. Based on personal observation the author then tries to show how the back-to-back events in Dhaka were fast fomenting the national psyche countrywide. The narrative gets blended with a series of commentaries from a personal and strategic viewpoint. For instance, he states on page 32 that though the fiery nationalistic speech delivered by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on March 7 felt awe-inspiring, but lacked a clear guideline on the topic of a systematic struggle in the road to independence. Simultaneously, he also points out a number of potential causes that may have prevented the leader from issuing a clear directive.

A number of readers may think it to be self conflicting in nature but, as far the message goes: it's the writer's personal understanding of a speech that's tagged with opinions. Here again he says that the top brass of the then Awami League lacked the organisational, material, and other resources to materialise the dream of independence shown through the speech. It's interesting to note and could become the subject of a live debate, 'if our predecessors had chosen to go to war based on this speech, and how war could have been waged if the military crackdown hadn't occurred in the early hours of March 26.'

However, even on the second edition he clearly mentions (it comes with a correction note in the second edition) that Sheikh Mujib had uttered 'Joy Pakistan' after he had said 'Joy Bangla'. The understanding about the statement is clear , even though it's not unanimously confirmed if the leader had actually said it or not. In general, if he hadn't uttered 'Joy Pakistan' then the room for Yahiya was open to declare him as a secessionist. Officially and legally - the People's Republic of Bangladesh was very much East Pakistan on 7 March, 1971.So if Sheikh Mujib had said 'joy Pakistan' then it wasn't confusing and of course not a political faux pas. What's seemed baffling is what took 43 years for this 'joy Pakistan' to resurface and why has it turn to be the book's apple of discord. Similarly, if Mr.Khandker is wrong then it's up to his opponents and historians to prove by submitting substantive evidence. If they fail to do so then the writer is correct. And if we are unconvinced then we have failed to preserve the undistorted version of that revolutionary speech.

What's missing in the chapter is that since Mr.Khandker so explicitly expressed his opinions about the speech besides the missing guideline for independence, but nowhere did he elaborately discussed who could have been the potential group of people that could have helped Sheikh Mujib draft a full-fledged military contingency plan for liberating the then East Pakistan? His observations as an air force officer is sharp as a hawk when he comments on how the then military junta was mobilising troops for a possible military crackdown on East Pakistan and how growing discrimination continued to isolate the Bengali officers of PAF. Undeniably, who could have experienced the scenes on a more close account?

On one hand the question naturally arises 'why despite repeated warnings about troops mobilisation through different channels failed to alert the high-ups of Awami League.'(As the author claims) And on the other 'was the relationship between Bengali officers of the Pakistan armed forces and our then political leaders strong enough based on which the troops build up could be deterred?' be as it may, the writer pushes you to rethink about the relationship between then Pakistan's state apparatus and politicians. Also, his views for military preparations in advance to counter 'Operation Searchlight' may seem impractical to many, but from his personal-cum-professional observations he thought it realistic.

It's not surprising, that being an officer he could gauge the fait accompli of a military crackdown a lot earlier than many and it's perhaps this reason why he emphasised more on a military solution than a political one. For example in page 44 he writes that 'if we could have waged war based on a clear set of directives issued by Bangabandhu then the lives of many thousands could have been saved....'

It has a general meaning but not clearly detailed, maybe it indicates of organising military strength, advance planning and guidelines to attack Pakistani forces even before 'Operation searchlight' had commenced. Here again a number of his personal suppositions are carefully crafted which seems like an attempt to create a dialogue between him and his reader.

One should be free to comment on what a leader should or shouldn't have done. Given the conditions that the remark is not abusive, strongly justified and properly explained. Till the end of this 29 page long chapter a short memoir is described about the post-crackdown days added with historical details.

The second chapter focused on the much talked about announcement of independence and the formation of interim government based on factual details. This 17 page chapter impartially analyses the widespread concepts concerning the announcement at depth. Here on page 61 he states that 'after the onslaught people really didn't much care for an official declaration...' but simultaneously explained its necessity. The latter half of the chapter detailed the formation of the interim government in exile.

The war's excitement begins from the 3rd chapter, titled 'joining the freedom struggle'. This semi biographical narrative explains how the author's patriotic fervour for joining the war had realised. Not only was he, a valiant freedom fighter, but also a one who contributed to the struggle from many sides. The suspenseful story strongly stitches the next episode which is the first-hand account on the history of our armed struggle by the creation of Muktibahini. (Liberation Army)

Shedding light on a number of issues from a purely military perspective, he reveals how clearly and profoundly the writer had observed the organising, training and operational activities of the Muktibahini. Intriguing in this chapter, was a description about deliberate attempts to politicise the war with its fighters, and sadly this had to happen in the time of a national struggle. This issue followed the flaws in the selection of freedom fighters, deficits in the quality of training the freedom fighters, reasons behind incurring huge losses of the Muktibahini during the first half of the war; inadequate supply of arms by the Indians up till the Indo-Soviet treaty signed in August; and decisions made by the joint forces on key military strategies. And all of these were captured first-hand by the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Bangladesh Armed Forces. What other account could be more reliable and more fascinating a read?

Nevertheless, it's the fifth chapter titled “Mujib bahini” that's surely added an extra layer of excitement. According to the writer, Mujib bahini or Mujib force was created by India's RAW (research and analysis wing) as a parallel force of Muktibahini that emerged with secret, and to a greater extent - questionable objectives. Though it's differently defined in the other sources, but whatever the force's background is, during the war it created enough misunderstandings that had negatively impacted the freedom fighters' solidarity. It wasn't only anti-Tajuddin or pro-Mujib but fostered Indian political aspirations for turning Bangladesh into an Indian satellite state. Regarding ' Mujib force', i would recommend a book for my readers named “Phantoms of Chittagong” written by Major General Sujan Singh Uban, under whose tutelage the force flourished in wartime India. The book is about the military exploits of the Indian Special Frontier Force known as the Phantoms of Chittagong and the Fifth Army. Referring to late Tajuddin Ahmed, the author wrote that the force was trained in Dehradun and secretly. Formed with men from educated and well-off Bengali backgrounds, the force was purposely reclusive at such length that India's Eastern High Command besides the Muktibahini didn't even know of its existence. As per the book the members of 'Mujib Bahini' never exceeded the limit of more than 10,000 during the war. (The figure is disputed)

Mysteriously enough, General Uban returned to Bangladesh after the independence to help form another force under the banner of 'Rakkhibahini.' After having known, a deeper investigation seemed only imperative to know more about Mujib Bahini's impact on the Liberation War. Moreover, its contribution as an auxiliary force of the Muktibahini also needs to be clarified.

On the last paragraph of page 145, a sentence reads that 'after independence some of the members of Mujib force had conducted the majority of looting…' what's confusing is how could a statement that mention no names and talks about looting raids carried out by a fraction after the Liberation War, be misinterpreted by some as 'defamatory for freedom fighters'? The sentence itself clearly points at no one and is that of a non-specified accusation.

The next two chapters' portrays the courageous role of 8 Bengali naval crew turned commandos, who had defected from a Pakistani submarine anchored in a French port. The reason was simple: to participate in the struggle for independence. The tale of their escapade till the ending of 'Operation Jackpot' (a codename for several naval missions carried out jointly by Mukti bahini) beats even the most nail biting thriller.

But the chapter on our air force should be explored by the reader. For this is also a success story, that echoes of indomitable will of the writer and other Bengali airmen, who had defected both from the PAF and PIA. These men literally built an air force from scratch; converting near obsolete civil aircrafts into bombers based on a remote airfield in north-east India.

The two chapters that proceeds till the final chapter with the surrender of Pakistan army in Dhaka are about background and historical details of forming the joint military command with the Indian army. It comes with how the criteria for decorating our freedom fighters with gallantry awards were decided; the writer's opinions and observations about its flaws and weaknesses.

In general the book is written in a semi-autobiographical manner that's enriched with chronicling of events, analysis and personal commentary. Considering the failures in political and military decision making a strong tone of grievance is felt while reading. The writer's political leanings have been carefully guarded too.

The reader may differ with Mr.Khandker's reading of characters and situations but cannot refute the pivotal role that he played as the war's deputy chief. If the book was meant to only record facts devoid of opinion and constructive criticism, then we would have surely missed the writer's personal reading of the war. Sometimes historical details are not chronologically arranged and placed rather sporadically. An extra chapter on Mujibnagar government's diplomatic initiatives would have added an extra value to the book. It's missing.

Additionally, it was a pleasure to have observed that despite having numerable opposing viewpoints with his superior and other wartime political leaders Indians included, the writer hasn't attacked any of them personally and, instead placed them in their deserved ranks.

A queer feeling after having read the book was that, it should have been written much earlier. Had it been written at least another two decades back would it have drawn the same response as it is drawing today? We will never know.

It's also sad to see, the book being used as a political weapon and if the damaging trend continues, then I fear few would dare to pick the pen to write on history unbiased.

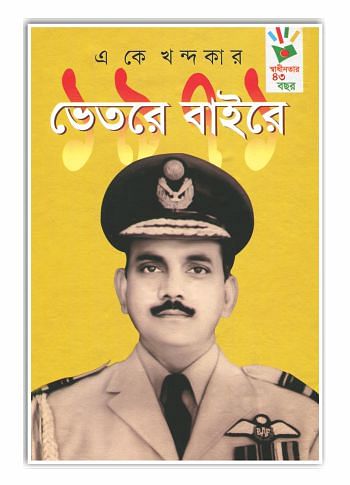

However, it was irritating to have seen that a spree of typos and wrongly spelled words still exists in the second edition. A separate section for photos would have looked better than a scattered arrangement. The book costing Taka four hundred and fifty may seem a bit overpriced. The cover photo only speaks of a handsome air force officer of a bygone era that grossly mismatches with the title name.

The bottom-line is: it's a recommended read, if you desire to be let-known of the personal interpretation and experiences of A.K. Khandker's appraisal of Bangladesh's Liberation War.

The writer is Editor, Book Reviews,

The Daily Star