Migration cost goes up, wages not so

Nurul Islam spent just Tk 17,000 when he migrated to Saudi Arabia for work in 1985 as his employing company paid for his visa and the airfare.

His monthly salary was around 400 Riyals. It took him two months to recover the cost of his migration. He could save a handsome amount too.

Today's reality, however, is different.

“Now the cost of migration is a lot more, but wages are low. It takes about two years to recoup the migration cost,” said Nurul Islam, 48, once a happy migrant worker in a security company, and now a migrant rights activist in Narsingdi working to create awareness.

He claimed that the state of the migrants has worsened over the years despite enactment of so many laws and building of new institutions to serve them.

The case of Mohammad Sabuj, 28, is a case in point.

Sabuj went to Qatar spending Tk 3.25 lakh that he borrowed on 30 percent annual interest from his relatives. He spent the amount for the trip as the broker, a relative in Qatar, told him that he could earn Qatari Riyal 2,000 (some 44,000 taka) a month as a driver.

Once he landed there, he found himself employed as a general worker in a construction firm that paid him 600 riyals as basic salary and 200 riyals for food, Sabuj of Noakhali told The Daily Star over phone from Doha where he works under the sweltering sun for 10 to 12 hours a day.

With overtime, his monthly earning is between Tk 20,000 and Tk 25,000.

“I still have a debt of Tk 1.5 lakh at home,” said Sabuj, who is uncertain when and how he would be able to repay the loan. He has been working there for three years.

Migration cost and wage may vary from country to country. A 2015 research found average migration cost of a Bangladeshi male during 2014 and 2015 was about Tk 3.8 lakh and for female Tk 1 lakh.

The research by Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit (RMMRU) of Dhaka University and Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation revealed male migrants send home Tk 2 lakh and female migrants Tk 80,000 a year.

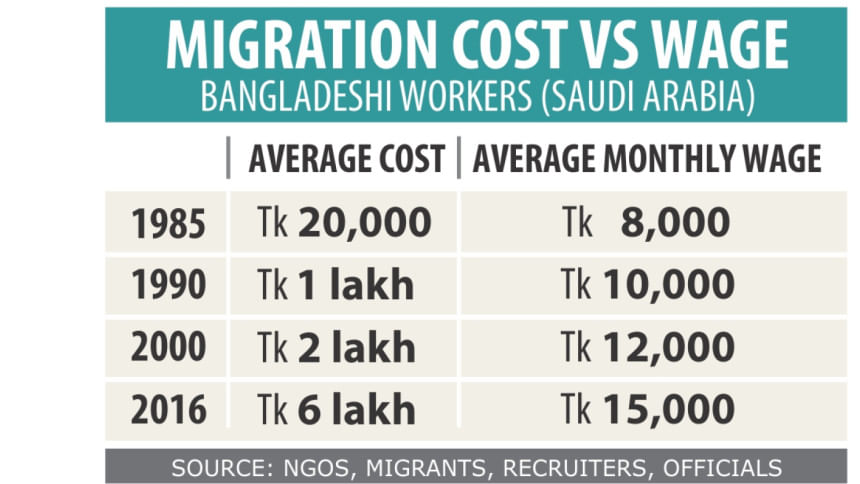

This means, for a male it takes nearly two years to recover his migration cost and for a female it takes 15 months, which was unthinkable in 1985 when Nurul worked in Saudi Arabia.

MIDDLEMEN MAKING IT WORSE

Experts and migrants said after Bangladesh formally allowed its citizens to work abroad in 1976, the employers would directly recruit workers, without using any middlemen.

Now, the middlemen seem to be all powerful.

“Many of today's recruiting agents used to sit with a typewriter to assist the jobseekers write official letters or to provide clerical assistance,” said CR Abrar, executive director at the RMMRU and a professor at the international relations department of Dhaka University.

As the demand for overseas jobs increased, the intermediaries started working as service providers. While a total of 6,087 Bangladeshis availed overseas jobs in 1976, it was over 6.07 lakh by October this year. Now, an estimated 80 lakh Bangladeshis work abroad, with over 70 percent of them in the Middle Eastern countries.

There were very few recruiting agents in 1984, when the government first allowed them to operate. The number is about 960 now. And, there are thousands of manpower brokers wooing jobseekers across cities and villages, often with false promises.

Even in the destination countries, some migrants turn into brokers and play a major role in collecting “job demands”. Nearly 80 percent work visas are now arranged by these brokers and the rest by licensed agents, said Abrar.

Prof Ray Jureidini in a study -- ILO White Paper on recruitment of low-skilled migrant workers in the Asia-Arab States corridor published this year -- said smaller companies prefer recruiting foreign labour through family and friends, who act as “referees” for the jobseekers. The friends and family members still get paid by the jobseekers.

The study said contractors and subcontractors who recruit foreign labour actually “outsource” their job to private recruitment agencies of the countries which send the workers.

Jureidini said, “Private recruitment agencies compete internally and internationally to obtain labour supply contracts by providing kickback payments to employing company personnel and placement agencies in the destination countries.”

These costs are finally passed onto low-skilled workers, violating the local labour laws and ILO convention that prohibits charging any fees on the migrant workers.

In contrast, the “employing companies save money and increase their competitiveness by not paying for recruitment costs and services,” said the study.

FRAUD RECRUITERS

As labour recruitment became a profitable business, unscrupulous individuals in the destination countries registered companies to recruit foreign labour. They just bring the workers into the country and provide them no jobs at all.

“For example, they open a company, recruit 50 or 100 workers and make money out of them. The migrants are then left alone,” said Osman Gani, a Bangladeshi migrant in Qatar, who worked earlier in Saudi Arabia.

“In Qatar you can see many Bangladeshi victims of such illegal activities. They came here spending a huge amount of money and are now without jobs,” he said over phone.

Similar practices were seen in Malaysia during 2007-08 when labour abuse drew global attention, prompting authorities to freeze recruitment from Bangladesh in early 2009.

“FREE VISA”

In Arab countries, many so-called employers hire foreign workers without any specific job and allow them to work as freelancers. This is illegal under the Kafala system (sponsorship system) which does not allow migrants to change jobs or return home without the permission of the employers.

This “freelancing” is marketed to aspirant migrants as “free visa”.

The so-called employers, however, charge migrants heavily for the “free visa” and when their visas are due to be renewed every year, said Osman Gani.

“If they don't comply with the 'employer's' demands, they can be reported to the police who then deport the migrants,” said Osama, who went to Qatar with “free visa” spending Tk 7 lakh in mid-2014.

OUTSOURCING

The involvement of labour outsourcing companies came to light prominently when Malaysia reopened Bangladesh's labour market in 2006.

Traditionally, it is the principal companies that recruited the foreign workers and pay them.

However, a new type of companies came into being that hire foreign labour, maintain a labour pool, and supply them to various principal companies on demand, said Mohammad Harun Al Rashid, a migration expert based in Kuala Lumpur.

The job contract here is between the migrants and the outsourcing companies, which takes a significant portion of the worker's wages and deprive them of benefits, he said.

“This created a situation in Malaysia in which thousands of Bangladeshis between 2007 and 2008 became jobless, underemployed, unpaid, and underpaid. Many were found confined to rooms,” Harun said.

“Such practice is akin to human trafficking and forced labour,” he said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments