|

Travel

The Culture of Sound

Andrew Eagle

|

View from a bell-tower. |

Standing in Farmgate, or at any other busy intersection in this everything-to-everyone city, you could be forgiven for thinking Bangladesh is the noisiest country on Earth. It's not just the cacophony of car horns, the deafening rumble of bus engines or the clamoring of rickshaw bells; there's the bargaining for vegetables, the shouting at someone in the way; the call of ticket-sellers and touts. There's one man on crutches calling out to his creator in the hope of alms; there's the clash of crockery at a tea shop, the feet on pavement, someone cracking the bones in their fingers and the snip of scissors at a pavement barber's. And being Bangladesh, there are hundreds of mobile calls in progress. Only Bangladeshis can hear that well! Yes, Bangladesh as noisiest country is a claim that would've set my head nodding in delighted agreement; at least it was so, before 2006, before I found the other contender to the title: Nicaragua.

Cultures have a sound. Bangladeshis know this, for on 21 February they celebrate their language in a way no other country does. Ekushey is recognition that language is an integral part of culture and self-identity; so too with sound.

Almost exactly on the other side of the world, in Nicaragua, lies the small city of Granada. The oldest colonial city in the Americas, it's the place I was fortunate enough to call home for five months in 2006. It's not a place that looks loud: set around a leafy square in a fairly regular street grid, Granada is sultry and tropical. To the east of the main square lies the shore of Lake Nicaragua, the vast expanse of brown that forms the largest lake in Central America and the city's best form of air-conditioning, when gentle lake breezes offer respite from the heat of the day. It should be tranquil.

A city of tradition, Granada is blessed with splendid Spanish-style villas featuring customary curve-tiled roofs and internal courtyards of palm trees and gardens. Street-side, houses are thick-walled and windows few; in every feature, the large wooden doors of each entrance and the use of columns and arches, the strong influence

of Islamic architecture on Spanish tradition is evident. In Granada though, you'll find no Muslims; instead small colonial-style churches are sprinkled here and there, with tall bell-towers in place of minarets. That Nicaragua is a very Catholic country is evident in Granada. It's a pious city. No, apart from the brash colour of the buildings, the mustard yellow, cool aqua, red ochre or lilac-trim, there's little visual stimulus to allude to the city's noise.

|

Catholic parade in Granada's streets. |

But in and around the main square, to the south in the bazaar area and further west where the new shopping district lies, at full voice the city shouts. Some of the noise is familiar to Bangladeshi ears: transport engines; the din of portable generators, for Nicaragua has that problem too; the clip-clop of horse-drawn taxis like the ones to be found in old Dhaka; the monsoon rain on the roof; the bargaining and begging and touting. Megaphones are used for canvassing, driven around town for an effect reminiscent of the death announcements and cinema advertisements you hear in a Bangladeshi village. Other sounds have Bangladeshi parallels, like the church bells that replace azaan or the screech of the souped-up cars of young drivers, ripping by at ludicrous speed, stereos blaring, which might compensate for the more restrained use of car horns in Granada. Still other sounds are unique.

Yes, to make up for the lower population, Granada with just 240,000 people and all Nicaragua with a population of only about 5.5 million, in a country only slightly smaller in area than Bangladesh, the help of amplifiers is required to increase decibels. Shops belch an array of drum beats and tunes, from Nicaraguan folk songs to Spanish pop, at a volume where going shopping can risk causing headaches; but to 'Nicas' it's normal.

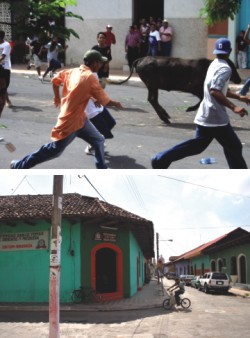

If that were not enough, Nicas have a penchant for festivals. Most festivals have an origin in Catholicism, and the Catholic calendar when properly played out is a busy one. It's not uncommon in Granada to accidentally run into a parade, church attendants at the front holding staves aloft, with flags, candles and a statue of some saint or the Virgin Mary; and at the back, most probably, will be a mariachi brass band, trumpets blasting and large drums pounding out a marching rhythm. There's the running of the bulls, more famous in Pamplona, Spain, when bulls are let loose to chase spectators down the streets. There's the parade of proud and strong horses from outlying estancias (farms), which curtsey and dance for peoples' amusement. These events, and of course weddings, are also suitable for brass bands.

With all the occasions, the brass bands need to rehearse and in Granada rehearsal's not considered a private activity, so they set up on the back of small trucks and play as they are driven around town in preparation for an upcoming event, regardless of the hour. It was on more than one occasion I was awoken at 3 a.m. by a brass band in full throttle being driven past my bedroom window. I could only sigh; happy I was there.

|

(Top) The 'running of the bulls' parade. (Bottom) Granada: it's not a place that looks loud. |

There's much to do around Granada: you can go kayaking on the lake or visit one of the volcanoes that create the fascinating dinosaur landscape that makes up much of the country. There's active Masaya volcano, where you can look down into a steaming, hot crater; a few years ago that volcano suddenly spit out a boulder that flattened a car. Closer to Granada is the extinct, water-filled Laguna de Apoyo crater, crystal clear and idyllic for swimming; and closer still, overlooking the town, is dormant Mombacho, whose hillsides are covered in jungle suitable for hiking. There you can see pillars of steam rising from cracks in the earth; but even the volcano-jungles, true to their nationality, manage to be noisy. Particularly in the mornings and evenings, when defending their territory of treetops, the howler monkeys bellow, a grunting rhythm that can be heard many hundreds of metres away.

The link between sound and culture plays true when you meet the people, the Nicas, for apart from the nearest neighbours perhaps, you'd be hard-pressed to find people more like Bangladeshis: friendly, sensitive, spirited and soulful, these are adjectives that apply to the people of both countries. Nicas might be a little shier, although my poor Spanish didn't help; nonetheless I found myself wondering if similar people make similar sounds, or if similar sounds make similar people.

In South Asia, arguably, nowhere is home to literature more than Bengal and in Nicaragua it's said 'a Nica is a poet until proven otherwise'. What a great saying!

As you celebrate Nazrul, Tagore and the others, Nicaraguans remember in statues and street names their great author and poet Rubén Darío (1867-1916), renowned throughout Central America and often regarded as founder of the Latin American literature movement called modernismo.

And in the deep wells of brown Nica eyes, where there's a complex concoction of despair, hardship, humility, joy and hope: a history as difficult as this country's, marred by dictatorship and war; the same worry of securing a salary, of finding a job at all; the beauty of landscape; the strong sense of community; in those Nica eyes I thought, yes, maybe a little, I could sense the spirit of Bangladesh.

Last February, in this city, as the tragedy unfolded in Pilkhana, I'm sure I was not the only one in nearby neighbourhoods to despair at the eerie silence in normally busy streets, the quiet that screamed all was not normal. I can't be the only one who hoped for a return to the raucous clash and clang of traffic, the hubbub of markets and life: all the sounds that make Dhaka. Thankfully they have returned, and with them my secret link to Nicaragua. For yes, if you stand at Farmgate and close your eyes, you might just be able to imagine Granada.

As evening yawns and most of Granada's sounds have gone home for the day, people open their doors and relocate to the footpath, the best place to enjoy the lake breezes funnelled along the streets. They sit in rocking chairs and chat with family members, neighbours and friends. Could it be the time, in the Bangladesh of Latin America, reserved for a little adda-in-Spanish?

Photos: ANDREW EAGLE

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |

|