Neighbours

Climate Justice

Nader Rahman

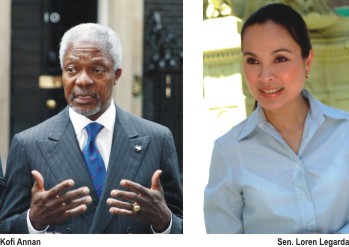

It is a useful concept, and to Kofi Annan, the former Secretary-General of the United Nations, must go the credit for popularising it. Sen. Loren Legarda also deserves approbation, for bringing the issue, in this new, evocative phrasing, to the Philippines' attention. But while “climate justice” may have its uses, it also has its limitations. It is a useful concept, and to Kofi Annan, the former Secretary-General of the United Nations, must go the credit for popularising it. Sen. Loren Legarda also deserves approbation, for bringing the issue, in this new, evocative phrasing, to the Philippines' attention. But while “climate justice” may have its uses, it also has its limitations.

Annan's Global Alliance for Climate Justice is essentially a worldwide pressure group based on the “polluter pays” principle; in this case, the polluters are the large industrialized countries, who account historically for an overwhelming share of greenhouse gas emissionsaccording to scientific consensus, the primary engine of global warming. Climate justice seeks to hold the developed economies to account, and to play a proportionate role in the global effort to lower greenhouse gas emissions.

The perspective of the developing economies is summed up in Legarda's statement: “It is a clear injustice that these groups [the poorest in the world] suffer the brunt of the impacts of climate change without any responsibility for having caused it.”

Perhaps “any” is too broad; it is difficult to pinpoint any sizable group of people in the world who do not leave a “carbon footprint.” But the larger point is surely accurate: The poorest people, who do not use air-conditioners or travel by jet, are the ones left most vulnerable to the adverse impact of climate change.

“Those most vulnerable to climate change today are the world's poorest groups, since they lack the resources and means to cope with its impacts,” Legarda, who was recently named by the United Nations as a “regional champion for disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation,” said after meeting with Annan at the Global Humanitarian Forum in Geneva two weeks ago. From Geneva, Legarda noted in a press statement that “99% of the casualties due to climate change occur in developing countries but 50% of the world's least developed nations account for less than 1% of greenhouse emissions.”

The issue is complicated by historical factors: China, for instance, is a leading user of coal power plants, the dirtiest source of energy; the momentum of its rapid economic growth over the last 30 years all but ensures that China will continue to consume extraordinary quantities of coal in the next couple of decades. And yet, despite this disturbing trend, historically China will have contributed much less greenhouse gas by 2030 than, say, Britain since the Industrial Revolution.

Will climate justice, as Annan's alliance understands it, calibrate the ecological scales in such a way as to accept such nuances?

Here we see the limitations of this useful, indeed necessary, approach. The main theatre of operation in the climate change wars, if we may borrow the language of the military, is the commanding heights of public opinion in the developed economies. Public behaviour in the United States, for instance, is a key determinant of the success of any new climate change framework; will millions of Americans opt to buy greener cars, or forgo buying cars altogether? Will millions of American households, so used to the conveniences of modern life, opt to change to an alternative, more difficult but less energy-intensive lifestyle? The answers will be shaped by American public opinion, responding in part to government initiatives, private-sector innovation and greater awareness of the ecological costs of development.

Is “climate justice” the best way to engage public opinion in the industrialized countries? Annan's concept allows countries at great risk of climate change, including the Philippines, to band together and work as one in pressuring developed economies. But perhaps the best way to engage public opinion in those same developed economies would not be in terms of “justice”it would be difficult enough to consider adopting an alternative way of life without taking the concerns of other people in other countries into accountbut in terms of reason, of economic good, of enlightened self-interest.

Philippine Daily Inquirer/Asian News Network

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |