India's plan to build a mega dam on the Barak river at Tipaimukh has stirred primal fears in Bangladesh. For the 150 million people of this low-lying delta, the rivers are the cradle of life. Bangladeshis depend on the river system for food, water and transportation. After the disaster caused by India's Farakka Barrage, Bangladesh can ill afford another monstrosity that will squeeze the rivers' life-giving flow. Public concern has been heightened by the extraordinary secrecy that has shrouded Tipaimukh from the beginning. Although Indian diplomats have been at pains to assure Bangladesh that Tipaimukh will not have the same ecological effects as Farakka, people remain fearful. Many critics have suggested the Tipaimukh Multipurpose Dam project could cause desertification of the North-east and allow salinity to move up from the Bay of Bengal. But the freewheeling debate about desertification may be masking more critical social and environmental consequences.

Photo: Syed Zain Al-Mahmood

Sitara Begum is a daughter of the Surma. She was born beside the river, swam in it as a teenager and when she got married, her bridal party rented 12 boats to make the ceremonial trip to her tiny fishing village perched on the riverbank. Now, a mother of three, Sitara looks to the Surma for her livelihood. Her husband Kalam is a fisherman.

Sitara's life is usually as placid as the waters that flow swiftly and silently past her village. But recently all has not been well in her world. There is talk of a big dam being built upriver in India. Sitara's husband and father-in-law discuss it every night over dinner. Sitara does not understand all that is going on, but she knows any changes in the river's life-giving flow would be disastrous.

“The river is our mother,” she says. “We catch our fish from it, bathe our children in it and take our vegetables and fish to market along it. If the river were to dry up, what would happen to us?”

Sitara Begum is one of nearly 20 million people who inhabit the floodplains of the Surma-Kushiara-Kalni basin. Most are connected to fishing and agriculture, and are entirely dependent on the bounty of the river system. The low-lying marshy areas are locally known as Haors. Enriched by the fertile silt deposited through the natural ebb and flow of the rivers, the haors serve as the rice bowl of the Northeast.

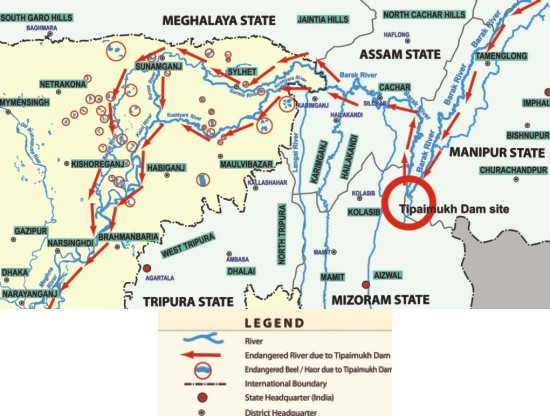

Given that rivers are such an important economic and cultural resource for Bangladesh, it is easy to understand why India's Tipaimukh Multipurpose Dam Project has caused an outpouring of public concern. India is building the Tipaimukh dam near the confluence of the Barak and Tuivai rivers in the southwestern corner of Manipur state, roughly 200 km from the Bangladesh border. The Barak enters Bangladesh at a place called Amalsidh, near Zakigonj in Sylhet, after splitting into the Surma and Kushiara rivers. The Surma and Kushiara in turn unite near Bhairab to form the mighty Meghna. The Surma-Kushiara-Meghna system -- supporting the livelihood of roughly 50 million people spanning 16 districts -- is one of the three main river systems in Bangladesh.

The Tipaimukh dam itself will be a rocky behemoth 500 ft high and 1200 ft across --the equivalent of a wall across the river as tall as a 50-storey building. Indian experts say the dam was originally designed to contain floodwaters in the lower Barak valley but hydropower generation was later incorporated into the project.

“The authorities claim it will generate 1500 MW of electricity,” says Dr. R.K. Ranjan Singh, prominent writer and Registrar of Manipur University, speaking to the Star during a seminar in Sylhet recently. “But a careful study of the specifics shows a firm capacity of only 412 MW.”

From the time it was first mooted in the early 70s, the Tipaimukh dam project has been shrouded in extraordinary secrecy. There was suspicion that the large dam was being planned without much attention to environmental and economic concerns. Data was hard to come by, and when the mandatory public hearings were held in Manipur, locals say they took place behind closed doors with the army guarding the perimeter.

Some of the loudest voices of protest have come from within India itself. India's own Arundhati Roy wrote, " Big Dams haven't really lived up to their role as the emblems of Man's ascendancy over Nature. It's common knowledge now that Big Dams do the opposite of what their Publicity People say they do - the Local Pain for National Gain myth has been blown wide open.”

The haors are unique ecosystems that support millions of people and a multitude of flora and fauna. Photo: Syed Zain Al-Mahmood

Rights groups in Manipur, Assam and Mizoram have been opposing the dam for decades, holding up its progress. In a memorandum to the Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh, the Action Committee Against Tipaimukh Project wrote in 2007: “The mega-dam proposed at Tipaimukh will smother this river; change its age-old knowable and reliable nature; and drown us all in sorrow forever! This project is not 'for the people.”

In Bangladesh, the country with potentially the most to lose from the dam, the opposition had been muted until recently. Although several environmental groups had raised the issue, and successive governments had asked their Indian counterparts to provide data on the project, nothing much was known. Meanwhile, the Indian government quietly floated international tender and completed preparations for construction. It was only when Shiv Shankar Menon, the Indian Foreign Secretary, arrived in Dhaka in April and requested the government to send a delegation to visit the site did environmental groups, political parties, and the people of the Northeast erupt in protest.

Since then, protesters at the almost daily rallies have criticised India's unilateral actions on a shared river. “We are a sovereign nation. We want to live in peace with our neighbours in an atmosphere of mutual respect. We ask that India desist from this act, which we do not consider neighbourly. Along with the people of Manipur, we will raise our voice against the Tipaimukh dam,” said Engineer Hilaluddin, Director of Angikar Bangladesh, an environmental group that campaigns against obstruction of river waters. “I call on India to let the Barak run free.”

<>B<>angladesh already has a complex and increasingly difficult relationship with water. River erosion, rising sea levels, increased salinity and arsenic in ground water pose formidable problems. Rivers in the North and Southwest have dried up, and saline water has advanced from the Bay of Bengal. Critics blame the Farakka barrage that India put into operation in 1975 for drying up large parts of the country, affecting navigation and adversely influencing the environment, agriculture and fisheries. Water resources experts also say India's dam on the Teesta river has affected the performance of Bangladesh's own irrigation barrage, seriously hurting millions of farmers in the country's north.

Faced with such intractable problems, Bangladesh can ill afford another monstrosity that will squeeze the rivers' life-giving flow. “What is power-luxury for India is a life-and-death question for Bangladesh,” said Prof Muzaffer Ahmad, president of Bangladesh Paribesh Andolon (Bapa), an environmental forum. “Energy cannot be more important than human disaster.”

Speaking to reporters at a round table on climate change, Muzaffer, a prominent academic and former chairman of Transparency International Bangladesh, said: “The rivers of Bangladesh will dry up during winter and overflow during the monsoon with the construction of Tipaimukh dam.”

He condemned recent statements by a couple of ministers that the damage could not be assessed before the dam is built. “Refrain from utterances that may harm interests of the country and the people,” said Prof Ahmad.

At a conference on the Tipaimukh dam on June 19, organised by Angikar Bangladesh and attended by Finance Minster AMA Muhith as chief guest, speakers called for national unity against the construction of the Tipaimukh dam forgetting political and regional differences. Dr Abdul Matin, General Secretary, Bapa, drew the attention of the conference to a mistake committed by Bangladesh in 1974 by agreeing to the Indian suggestion of a “trial run” of the Farakka barrage. That trial run never stopped.

The passionate opposition to the Tipaimukh dam has so far focused on the possibility of desertification and increased salinity. It is easy to draw comparisons with Farakka. But the freewheeling debate about desertification may be hurting, not helping, Bangladesh's cause.

Indian diplomats have been quick to point out the differences between Farakka and Tipaimukh. “The so-called experts in Bangladesh are using scare tactics,” said the Indian High Commissioner to Bangladesh Pinak Ranjan Chakravarty in an aggressive tone that surprised many in the diplomatic circles. “This is a hydroelectric dam. In order to generate power, it must release water. So, Bangladesh will probably get more water in the dry season.”

The High Commissioner's not-so-diplomatic pronouncements irked many people, but leading water experts seem to agree with him -- for at least part of the way.

“We have to understand the difference between a dam and a barrage,” says Professor Jahir Uddin Chowdhury of the Institute of Water and Flood Management at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (Buet). “A dam is a large wall or barrier that obstructs or stops the flow of water, forming a reservoir or a lake. Electricity is produced by using the potential energy of the dammed water to drive turbines. A barrage is a specialised dam with sluice gates often used for irrigation and flood control.”

Prof Jahir says the Indian Multipurpose Project envisaged a barrage 100 km downstream from the dam at a place called Phulertal. “If India builds the Phulertal barrage then a Farakka-like scenario may become reality. If, on the other hand, they just build the Tipaimukh hydel dam, water will probably increase during the winter what we call augmentation. In this scenario, we have to carefully assess the downstream environmental impact.”

Water resources expert Dr Ainun Nishat believes more data on the design and operations of the Project are needed to decide whether the flow will increase or decrease during wet and dry seasons, but he suggests in either case the effect on the Surma basin will be destructive.

The haors or flood plains of the Surma basin are unique ecosystems home to a rich variety of flora and fauna. Parts of the region have been designated Ramsar sites of international importance, and protected by the Bangladesh government as Ecologically Critical Areas (ECA). The total area of this wetland covers nearly 25000 square kilometers and supports approximately 20 million people.

The wetlands of the Surma basin perform two crucial functions: they serve as the granaries and fisheries of the Northeast. Many of the species inhabiting the haors will be threatened by loss of habitat, but more importantly it is the people of the wetlands who might be on the endangered list if the Tipaimukh dam goes ahead.

Rustam Ali, 71, is a farmer in the Northeastern district of Sunamgonj. His weather-beaten face tells the bittersweet story of rice production. “Because of the water, we can grow only a single crop the Boro. We plant when the water recedes in the winter, and harvest before the monsoon waters come. Because of the silt deposited by the floods, God willing, we always have a bumper crop.”

The hilly parts of the Northeast are not fertile, and therefore the rice mills of Ashugonj, Bhairab and elsewhere are heavily dependent on rice from the lowlands. The farmers and rice traders bring the rice on wooden longboats, navigating skilfully across the floodplain.

The rivers are woven tightly into the lives of the haor people. They literally live by the ebb and flow of the waters. Any artificial alteration of the “flood pulse” could affect food security and bring disaster to the region.

“If the water increased in the Surma and Kushiara during the dry season, the haor would be waterlogged. We would not be able to plant,” says Rustam Ali “there would be no harvest.”

The fishing community would also be badly hit. “When the water rises in the river during the monsoon, the fish go into the haors to spawn,” says Raquibul Amin, Programme Coordinator for the World Conservation Union (IUCN) Bangladesh. The flood not only carries fish larvae but much-needed nutrients into the haor which turns into a vast nursery for fish. When the water recedes in the winter, the fattened fish move out into the rivers and are caught in the nets of the fishing villages lining the riverbanks. If the wetlands were waterlogged, the seasonal rhythm of the fish would be seriously hampered.

Studies of large hydroelectric dams worldwide have shown the artificial flattening of the “flood pulse” adversely affects lower riparian fishing and agricultural communities. A study carried out by the Helsinki University of Technology on the Mekong River found that hydroelectric dams in China drastically reduced the load of fertile sediment carried by the monsoon floods, affecting the fertility of the Mekong's fisheries in Thailand, Laos and Cambodia.

|

| The rivers are embedded in Bangladeshi culture, inspiring generations of poets. |

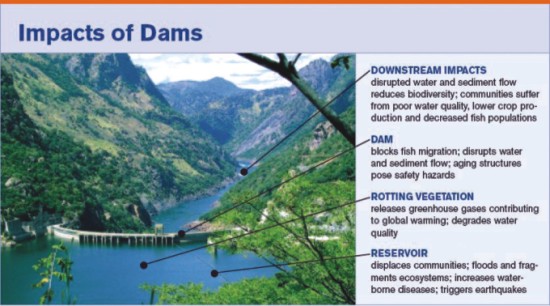

Dams and barrages often have a negative impact on river flow. Photos: Syed Zain Al-Mahmood |

Some experts suggest that the Tipaimukh dam may help control flash floods, but others have warned of worse flooding to come. “The dam and the reservoir have certain limitations,” says Dr Jahir Bin Alam, head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Shahjalal University of Science & Technology. “The dam may control some of the annual flooding. But when there is a really big rise in water levels, the gates will have to be opened to save the dam itself. That will lead to a much bigger flood downstream.”

There are other aspects of large hydroelectric dams that are well documented but much less well known. The major hydrological impact of such dams is to impose on the river an unnatural pattern of flow variations. As the environmentalist Wallace Stegner puts it, “a dammed river is not only stoppered like a bathtub, but it is turned on and off like a tap.”

The Mekong River Commission has held hydroelectric dams responsible for bizarre fluctuations in the river flow in recent seasons. As the turbines are switched on and off to meet changes in electricity demand, their reservoirs empty and fill -- and the river downstream sees fluctuations in water levels of up to a metre a day.

In 2000, the World Commission on Dams found that the “changed hydrological regime of rivers has adversely affected floodplain agriculture, fisheries, pasture and forests that constituted the organising element of community livelihood and culture.”

A dam holds back sediments and nutrients that would naturally replenish downstream ecosystems. Deprived of its sediment load, the “hungry” river seeks to recapture it by eroding the downstream river bed and banks, undermining bridges and other riverbank structures. Riverbeds downstream of dams are typically eroded by several meters within the first decade of commissioning of the dam. International hydrologists say the damage can extend for hundreds of kilometres below a dam.

Even more alarming is the finding that riverbed deepening will also lower groundwater tables along the course of a river, threatening vegetation and local wells in the floodplain and requiring crop irrigation in places where there was previously no need. With ground water tables already seriously low in Bangladesh, further lowering would precipitate a crisis in urban areas hugging the rivers, such as Sylhet, Maulvibazar and Habigonj.

Protests against the dam have been passionate and sustained. Photo: Angikar

The Indian High Commissioner Pinak Ranjan Chakravarty has rubbished claims that the Dam would be harmful for Bangladesh. He dismissed worries that the reservoir may cause seismic disturbance in quake-prone Manipur, saying, “There is absolutely no evidence that dams cause earthquakes.” But the High Commissioner may be on shaky ground.

Worldwide, there is a growing body of evidence that shows earthquakes can be induced by very large hydropower dams. The most serious case may be the Richter 7.9 magnitude Sichuan earthquake in May 2008, which killed an estimated 80,000 people and has been linked to the construction of the Zipingpu Dam. In a paper prepared for the World Commission on Dams, Indian scientist Dr. V. P Jauhari described this phenomenon, known as Reservoir-Induced Seismicity (RIS). “There is a positive correlation between the height of the water column in the reservoirs and the seismicity induced,” wrote Dr. Jauhari.

|

| For impoverished villagers along the Surma, the river is the cradle of life. Photo: Syed Zain Al-Mahmood |

Millions in the low-lying Haor areas depend on a single crop. Photo: Syed Zain Al-Mahmood |

Dr Soibam Ibotombi of the Department of Earth Sciences, Manipur University warns: “The likelihood that during 1991-2015 the (Tipaimukh) region would experience an earthquake of magnitude 7.6 is between 40 and 60 per cent.” Based on a dam-break study conducted as part of Bangladesh's Flood Action Plan 6 (FAP-6), international hydraulic and environmental experts concluded that in the event of a dam failure at Tipaimukh, a wall of water more than 15 feet high would reach Sylhet within 24 hours.

Faced with a public outcry, the government of Bangladesh has adopted a wait-and-see approach, with several ministers citing Indian claims that the dam would not harm Bangladesh. Mir Sazzad Hossain, member of the Joint River Commission told the Star that although India would have sole control over the river flow, the Indians had “assured” Bangladesh that they would not build a barrage on the river, or divert any water. But the low-key approach has been criticised by environmentalists who think the government should do its homework and come out strongly against the dam.

“If you put a 50-storey building right in the middle of a living river, no matter how many windows there are do you want to tell me there will be no damage to the ecosystem?” asks Engineer Hilaluddin of Angikar.

Many experts have also been critical of the decision to send a parliamentary delegation to visit the site. “The dam has not been built, so there is nothing to see but the hills, the river and the sky,” says Ramananda Wangkheirakpam, an environmentalist in Manipur. “The Indian government needs to show it is not breaking international conventions in order to attract foreign investors. We are afraid this visit will legitimise the Dam.”

The Guidelines issued in 2000 by the World Commission on Dams clearly state that a dam should not be constructed on a shared river if other riparian States raise an objection that is upheld by an independent panel.

|

| Thousands of fishing villages will be affected by the dam upstream. Photo: Syed Zain Al-Mahmood |

The rivers are vital arteries for trade and transportation. Photo: Syed Zain Al-Mahmood |

Neither Bangladesh nor India has signed the 1997 UN Convention on International Watercourses, but Dr Asif Nazrul, Professor of Law, Dhaka University feels it is still the basis for international edict on shared rivers. “The 1997 Watercourse Agreement requires every state to refrain from undertaking any unilateral project on a transboundary river,” says Dr Nazrul. “The Ganges water treaty between India and Bangladesh also says the same thing, and India's actions are contravening that. Both India and Bangladesh should reach a solution respecting the letter and spirit of international law.”

Prof Jahir Uddin of Buet suggests a basin-based approach by “bringing all the Riparian countries sharing the river to the table. We must ask the Indians for full disclosure and all relevant information should be made available to experts in Bangladesh. If we can protect the common river's natural wealth that will promote regional peace and prosperity.”

Worldwide, the dam debate is rooted in the wider, ongoing debate on equitable and sustainable development. The World Commission on Dams declared in its final report that while “dams have made an important and significant contribution to human development, in too many cases an unacceptable and often unnecessary price has been paid to secure those benefits, especially in social and environmental terms, by people displaced, by communities downstream, by taxpayers and by the natural environment.”

The Farakka barrage has devastated rivers in downstream Bangladesh. Photo: Zahedul I Khan

The Indian government clearly believes a dam at Tipaimukh will bring lasting benefits. Sitara Begum, Rustam Ali and 20 million other Bangladeshis may be excused for wondering why they should be stuck with the price tag.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009