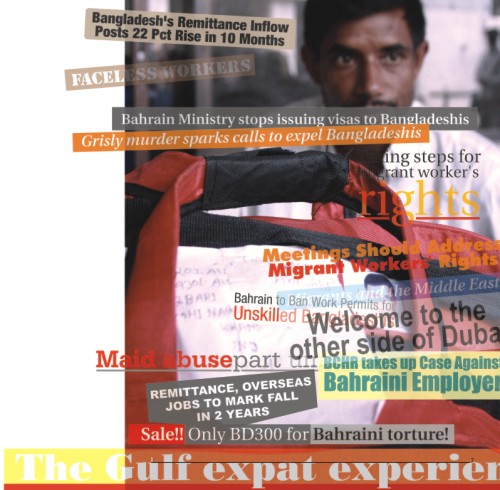

| Cover Story

Neglected Heroes

Hana Shams Ahmed

Around 90,000 Bangladeshi migrant workers live and work in Bahrain, 10 per cent of the total population of that country. In the year 2006-07, these migrants sent $80 million in remittances home. But the recent murder of a Bahraini man by a Bangladeshi worker has sparked angry reactions from government officials and politicians. The Bahrain government has put an embargo on recruitment of any further 'unskilled' workers from Bangladesh. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Malaysia had already put restrictions on Bangladeshi labourers, sparked by earlier incidents. As often highlighted at conferences and seminars, foreign remittance is the second highest foreign currency earner for Bangladesh. But apathy from our embassies, corrupt middlemen, flawed immigration policies, lack of a robust government response and disparities in labour laws have placed hard-working men and women in international news headlines for the wrong reasons.

On May 23, 37-year-old Bahraini Mohammad Jassim Dossary got into a heated argument with a 32-year-old Bangladeshi mechanic in a garage. At one point during the argument, the mechanic allegedly slit the throat of Dossary with a hacksaw. Dossary died before he could reach the hospital. The argument was apparently about payment for work done on his car. The Bangladeshi mechanic asked for 1.5 Bahraini Dinar for his work, but Dossary refused to pay more than 1 Dinar. Dossary was killed for the extra 500 fils (around Tk 90) he refused to pay.

A knee-jerk reaction from the Bahraini government to stop issuing work permits to

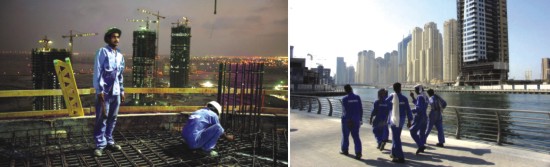

Building towers in booming countries. Who is going to ensure decent living conditions for them and that they get their regular paychecks? Photo: The Internet |

Bangladeshis ensued and fuelled an all-out rage against the country's expatriate communities, especially Bangladeshis. A Abdul Halim Murad, a Bahraini MP, called on the government to “put a timetable for the deportation of Bangladeshi labourers from Bahrain after their repeated involvement in murders and other crimes” and called for the execution of the accused man quickly “so that justice would be done”. In an incident two years ago, Mizan Noor Al Rahman Ayoub Miyah, a Bangladeshi cook, was convicted of murdering a high-profile fashion designer Sana Al Jalahama. Although the incident took place in 2006, a decision to execute Mizan by firing squad came right after the latest incident involving Dossary. Following a visa clampdown in Bahrain on all unskilled Bangladeshi labourers, leaders of the Bangladeshi community, in collaboration with the Bangladesh embassy in Manama, set up a crime watchdog The Bahrain Bangladesh Samaj (BBS). If the incidents in Bahrain were not bad enough, Bangladesh's largest labour market Saudi Arabia, home to around 15 lakh Bangladeshis, imposed a ban on recruitment of Bangladeshis in the household and agriculture sector. Thousands are also being forced to leave Saudi Arabia because it unofficially stopped renewing residential permits to Bangladeshis. According to government sources, the decision was taken in view of the fact that the quota fixed for Bangladeshi workers in the Kingdom was over. But the minister's clarification came amid rumours that the Kingdom had halted hiring Bangladeshis because media reports alleged that they were involved in “most criminal acts in the country”.

Several highly publicised immigration meltdowns have contributed greatly to an international black eye for Bangladeshi migrants. In one incident of pent-up worker frustration, more than 700 Bangladeshi workers stormed the Bangladesh embassy in Kuwait in April 2005, causing damage inside the premises. The protesters complained that they had not been paid for five months and demanded Embassy officials take action. Although in this case, it was the embassy and the unscrupulous middlemen who were targets of worker rage, the Kuwaiti government took this opportunity to begin blacklisting Bangladeshis.

On their way to a foreign land. The government must ensure their basic rights when working abroad. Photo: Zahedul I Khan

In late 2006, Kuwait stopped hiring manpower from Bangladesh on grounds that Bangladeshis “resort to crimes”. The embassy incident was not mentioned. Malaysia stopped issuing fresh visas in October 2007 following a fiasco in which hundreds of Bangladeshi workers fell victim to fraudulent middlemen in collusion with Malaysian employers. Television imagery of hundreds of Bangladeshis, stranded in Malaysia, fuelled fears of the 'illegal immigrants' from Bangladesh. The workers were eventually flown back home empty-handed. The long-term damage from the incident may have ripple effects in other countries.

Ever since the Middle East oil boom in the 1970s, and the economic boom of South-East Asia in the 1980s, millions of workers have been going to these countries from developing countries such as Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. The six states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) -- Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates -- are home to approximately ten million foreign workers, with the largest number in Saudi Arabia.

Behind the glittering exterior of high-rise buildings, flashy malls, opulent hotels and real estate is the story of wage exploitation by greedy employers, indebtedness to corrupt middlemen, hazardous working conditions and inhuman living conditions termed 'labour camps'. Although all these countries have strict labour laws, most remain un-enforced. While Bangladeshi politicians and policy makers pat their own backs every year on the increase in remittance flow, little is done in terms of regulation of this sector.

Photo: Drishtipat

A 2006 Human Rights Watch report, 'Building Towers, Cheating Workers: Exploitation of Migrant Construction Workers in the United Arab Emirates', highlighted significant abuses inflicted on unskilled migrant workers. Extremely low wages, routine withholding of wages for months, confiscation of passports as 'security' to keep workers from quitting, is the reality of migrant Bangladeshi workers. The overall industry is termed as the notorious '3-D jobs' -- dangerous, dirty and demeaning.

While the latest incidents show a trend of criminalising of Bangladeshi migrant workers, it comes after years of abuse endured by them, with little or no attention from the authorities. In 2002, Amnesty International heavily objected to the decision by the UAE government to the execution of three Bangladeshi nationals, which failed to meet international standards of fairness. Mohammad Zahar Abdul Sattar, Anwar al-Zamaan and Anwar Khan Mohammad were convicted of rape and murder of a Sri Lankan national. Yet their lawyers stated that while in detention all three men were repeatedly beaten, their legs were bound and the soles of their feet beaten bloody with batons. The lawyer also said that the accused did not understand the court proceedings because it was in Arabic.

The root causes of migrant dissatisfaction needs to be scrutinised further. Lower wages, compared to local compatriots, forced labour and constant abuse are realities that everyone should look into more deeply. In 2002, a Bahraini man was jailed for three months after being convicted of torturing a Bangladeshi employee. The 35-year-old victim told police that his employer had tied him up with a rope, beat him and then gave him electric shocks. In his defence, his employer said that he was trying to 'frighten' the worker so he did not run away.

|

Overworked and underpaid. The Bangladesh government's

indifference towards the welfare of the migrant workers could

ultimately hit the economy of the country. Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

Training migrant workers -- on skill and language -- is a necessity before they leave the country. Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

Human Rights Watch reported that suicides among construction workers were on the rise and said they were mostly stress related. Many workers cheated by their employers, unpaid for months, unable to pay back loans taken from home and trapped in a hostile country, opt to take their own lives. Psychiatrist Dr Shiv Prakash said in an interview with Construction Week (a Dubai-based weekly on the construction industry), “They know that they are in a bonded labour type of situation and are reacting to what they think is the biggest mistake in their life, an irreparable loss. It is the reaction to this loss which can lead to suicidal contemplation.” The Migrant Workers Protection Society (MWPS) based in Bahrain reported more than 20 cases in 2005 of rape and physical abuse of foreign housemaids to the police over a period of two-and-a-half years, but none resulted in a conviction.

The Bangladesh government imposed a ban on women workers, aimed primarily at those leaving to be domestic workers in the Middle East, where most reports of physical and other abuses came from. Despite the ban, thousands of women kept leaving the country seeking work abroad. The ban was eventually lifted as it was impossible to implement. Rather than these bans, it is more important for the government to safeguard the rights and working conditions of Bangladeshi women workers abroad. The government should monitor how Bangladeshi domestic workers are treated by their foreign employers. Language training to help them communicate with law enforcement agencies would be more helpful than a ban.

Selling all they have to pursue their dream of a decent life. Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

The plight of the workers begins at the source countries, where they are forced to pay exorbitant fees for employment contracts. According to the Ain O Salish Kendra's 'Human Rights in Bangladesh 2006' report, the government authorised cost for travel to the Middle East is about Tk 40,000 to Tk 50,000 but workers often end up paying Tk 200,000 to the recruitment agencies. Corrupt middlemen take advantage of the workers' lack of education and make them sign papers they don't understand. In Saudi Arabia, for example, the only contracts with legal validity are those written in Arabic. Many migrant workers never see these Arabic-language contracts in their home countries. Some contracts are translated into local language, but the terms and conditions are overstated. There have been stories where workers signed contracts with local recruiting agents, and these contracts were confiscated after they arrived in the receiving countries. Because migrant workers are so eager to send money back, and because of the lack of bargaining power on arrival at a foreign country, they have no choice but to accept lower wages and other contract changes.

In August 2007, 128 Bangladeshi workers who were promised 'respectable' jobs as computer operators and service workers found themselves stuck with no food and water at the Kuala Lumpur International Airport in Malaysia with no sign of the outsourcing agency officials coming to receive them. Even when they were received, they found themselves 'imprisoned' in a single room that resembled a storage facility where they were given 10 kilos of rice for two days, which they had to cook for themselves. All the 128 people had to make do with a single bathroom. Not only were they cheated by their recruiting agency in Bangladesh, they were kept in appalling conditions by the outsourcing agents and their own embassies were indifferent to their helpless situation. After giving more than two lakh takas each to their recruiting agency (when the government approved rate was Tk 85,000) they came back to their country empty-handed. Many of the workers had taken loans and many had sold off land to pay the agencies. What was different about the workers in Malaysia was that they were not unskilled labourers -- the favourite target of unscrupulous middlemen. These young men were all educated, mostly college graduates, hoping to get technical jobs overseas.

Bangladesh Association of International Recruiting Agencies (BAIRA) gives NOCs (No Objection Certificates) to the government on recruiting agencies, based on which the government then gives license to a particular agency. Currently 786 recruiting agencies are members of BAIRA. “We try to encourage our members to be respectful of the law and abide by the rules because after all we are dealing with human beings here,” says President of BAIRA, Ghulam Mustafa, “the recruiting agents should be educated, they should have good communication skills, be ethical, maintain a certain standard, and have no criminal background.”

Mustafa complains that instead of focussing on the positive side of the recruiting agencies, the media subjects the agencies to “humiliation and aspersion”. He says that there are arbitration committees which deal with expatriates' complaints. “The recruiting agencies are bound to accept our arbitration,” says Mustafa, “or we can take steps to cancel their license.”

Mustafa also said that about 100 of the recruiting agencies are now imparting training to workers before they leave the country. He points out that it is very important for the government to increase the budget allocation for this sector. “This sector demands more positive attention from the government,” he says and adds, “the government should declare it as the thrust sector of the economy.”

But Dr Atiur Rahman, Professor at the Department of Development Studies in Dhaka University, is more critical of the agencies. He says, “There is a lack of transparency in how these agencies work,” says Rahman, “licences of the corrupt recruiting agencies should be cancelled.”

Remittance inflow maintained an upward trend, growing by 286 percent from 1990 to 2007. In the financial year 1990-91 the total remittance inflow into Bangladesh was USD 763.91 million. By 2006-07 it had gone up to USD 6 billion. Saudi Arabia accounted for 29% of the entire remittance inflow in the last financial year (Source: Foreign Exchange Policy Department, Bangladesh Bank).

Dr. Atiur Rahman emphasises that regulating this sector is of utmost importance and restrictions put on Bangladeshi workers will have a very bad effect on the total flow of remittance. “Even now 90% of the remittance originates from the unskilled labourers,” says Rahman, “our skilled development process is very slow.”

In their earnestness to send money back home, many migrant workers accept lower wages and harsh working conditions when they are in the host country. Photo: Internet

Rahman suggests drawing up a comprehensive database on details of migrant workers. “Besides skill training they also need to be trained on what they can and cannot do in a different culture,” says Rahman, “our labour attachés in different countries are not in touch with these labourers. Each of these embassies should have a help line so that in a crisis they can rescue them.”

In insular societies with impenetrable walls propped up by suspicion, it is no surprise that host countries are quick to condemn whole peoples, nations and even civilisations due to isolated incidents. The backlash on the Bangladeshi migrants after the bomb blasts in Jaipur recently is an important lesson that whole minority groups can be made targets of racial/communal hatred based on a single incident.

Bangladesh must look beyond stopgap measures, and look at empowering migrant workers before they leave the country and respond to their needs while they are overseas. Countries must ensure migrants have access to justice and support services, including full translation facilities. Bangladesh must aggressively regulate the manpower industry immediately. Agencies that have been found to abuse workers even once must have their entire licenses cancelled. Training on language and culture of host countries must be made compulsory for all migrants. Our current diplomatic mission capacity should be enhanced with the recruitment of professional graduates who can fully address the problems of the workers. Before the domino effect of bans on our migrants spreads to other countries, our government must fight these scare tactics in the foreign media. New labour markets should also be targeted for expansion. Diplomatic missions must make sure migrants accused of committing crimes have access to interpreters or legal aid. Migrants who suffer abuse should have access to shelter, legal aid, medical care, and temporary residence status. They should also take up wage disputes with the governments of the host countries to make sure they are resolved fast and in a transparent method.

An estimated 50 lakh Bangladeshis are working abroad around the globe. Of them, about 30 lakh living in the Middle East send approximately 70 percent of the total remittance received by Bangladesh. It is the toil of the hard-working men and women that is helping, not only to make our households financially sufficient, but also strengthening the economy of this country.

If newspaper space and the number of seminars and symposiums are anything to go by, remittances are of national significance. If that is so, then the welfare of the people behind the remittances needs to be considered of equal national interest.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008 |