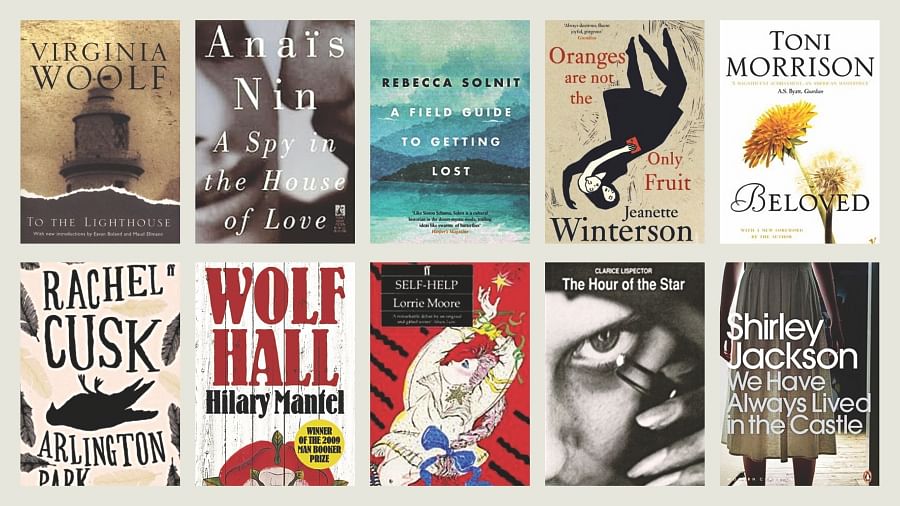

TEN BOOKS BY WOMEN that everyone should read

There are many perplexing moments in teaching creative writing, but perhaps none more depressing than the admission from some of the male students that they haven't read many—or in some cases any—books by women. This also goes, I might add, for some of the female students. I often ask them to tell me which female writers they have on their shelves and some might come back with the lone copy of Pride and Prejudice or To Kill a Mockingbird that they were forced to read at school but it's surprising and depressing to realise how true Grace Paley's statement is, “Women have

always done men the favour of reading their work—the favour has not been returned.”

If you're looking to expand the territory of your reading material, and read more women in 2014, you could do a lot worse than starting with some of these—which in a way also makes up a fantasy reading list for a course in Women and Literature:

1. Virginia Woolf – To the Lighthouse.

Perhaps starting with the obvious, but this is work from one of the most fluent prose stylists, ever, period. There is as much joy for the reader in her occasional prose and her essays and diaries as there is in her novels. The sheer level of poetry and clarity in her work still sings to us down the years. Start with To the Lighthouse and then the essays and then Mrs Dalloway, The Waves, Jacob's Room. You can't have pretentions to be well read without having absorbed some of her beautiful and complex prose.

2. Anais Nin – Spy in the House of Love.

The original provocateur, sexual adventurer, and lover of Henry Miller and his wife—among many others—was Anais Nin. You could do worse than start with Spy in the House of Love—a modernist text drenched in symbolism and sexuality but the diaries are worth reading too as works of intense self-analysis as well as the erotica which is actually radical and sexy. Interesting that she should be back in vogue again too in the age of the 'selfie'.

3. Rebecca Solnit – A Field Guide to Getting Lost

There is a rich vein of poet philosophers among women writers from Simone Weil to Sara Maitland to Diane Ackerman (whose Natural History of the Senses didn't quite make the list)—one of my favourites in this vein is Rebecca Solnit who writes with great passion and intelligence about politics and creativity and her own life. Her best book for creatives everywhere is the sublime A Field Guide to Getting Lost—a series of meditations on life and art and living the creative life, which is like a box of gifts. To be read slowly and meditatively.

4. Jeanette Winterson – Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit/Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?

Where would a list like this be without Jeanette Winterson? The Po-Mo high priestess/provocateur who is at her best when tackling her real life. The novel Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit and then the companion piece the memoir—Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?—are the pieces which will outlast her in popular memory. Both accounts of her strange childhood, snapshots taken thirty years apart, one fiction and the other memoir, which ask all kinds of interesting questions about art and lies (another of her subjects). The rest of her oeuvre seems too directed inwards—at the academy—rather than a more general readership and steeped in the fashion for the postmodern— something which in our more anxious confessional times seems out of date.

5. Toni Morrison – Beloved

Beloved is her best novel, but The Bluest Eye is also heart-breaking. Like many women writers she tackles identity, and the search for selfhood in an environment that denies it. In Beloved the central character would rather kill her own child than have her taken into slavery. Written in a gauzy, poetic style which expresses too the difficulty of achieving identity in a world that denies your voice.

6. Rachel Cusk – Arlington Park

One of the commonplaces of gender politics in literary studies is the notion that men write about the world while women write about the domestic, and why would the kitchen be interesting to men? Rachel Cusk might be persuasive on this point. She brings the death ray of her intellect to play on the middle class mothers of Arlington Park, one of her most satisfying novels and she has written controversially in memoir form about her own difficult experiences of motherhood. Like Lionel Shriver, she is a divisive figure, but with good reason because she punctures so wholeheartedly the idea of the domestic goddess (what Virginia Woolf calls Killing the Angel In the House) with a sharpness and a clarity of expression that is often coruscating, but always invigorating.

7. Hilary Mantel – Wolf Hall

Then we have a whole slew of novelists who stick pretty much to the 19th C model of the form: Margaret Atwood, Sarah Waters, Hilary Mantel. Works of huge imaginative scope and range that the reader can get lost in. Yes Margaret Atwood dabbles in speculative fiction and Sarah Waters' work can sometimes feel like an ersatz Wilkie Collins. Of these Mantel is for me the contemporary genius—the use of free and indirect speech in Wolf Hall is astonishing, as is the breadth of her imagination. Donna Tartt is in the mix somewhere too for the sheer chutzpah of taking ten years to write a novel as big and ludicrous and as grandly imagined as The Goldfinch.

8. Lorrie Moore – Self-Help

Women write great short stories too . . . Alice Munro is the acknowledged queen of the form, her work is so full of beady insight into human motivation and what she can do with time in a short story is astonishingly difficult to achieve. There is also the work of Lydia Davis whose short 'flash' fictions can pack as much of a punch as any longer work. Woolf's contemporary Katherine Mansfield is as much of a mistress of the story as Chekhov too. But my choice here would be Lorrie Moore, but only because she has a new collection of stories out this year, and the seminal Self-Help is still inspiring generations of new writers and readers.

9. Clarice Lispector – The Hour of the Star

Into this mix we must consider the writers who create their own forms. Clarice Lispector, a Ukrainian Jew raised in Brazil, danced entirely to her own tune. She started writing and publishing in her 20s and became friends with another difficult writer, the poet Elizabeth Bishop. Lispector's work is both tart and surreal without being whimsical and is newly republished by Penguin Modern Classics. The place to start would be with The Hour of the Star—her strange and haunting last work about poverty and identity.

10. Shirley Jackson – We Have Always Lived in the Castle

Another republished author set to make waves this year, Shirley Jackson is the author of The Lottery—the most controversial short story ever published by the New Yorker. If you haven't read it, read it before you read about it, the story depends on a clever twist that shocked and outraged the contemporary audience. Her novels are being republished this year to coincide with a new biography, but like the equally twisted Patricia Highsmith, Jackson's work is dark and unsettling. We Have Always Lived in the Castle is one of the creepiest books I have ever read and I am looking forward to reading more this year.

Acknowledged omissions — no 19th C novelists — well that would be a reading list in its own right: Austen, George Eliot, The Brontes, Mrs Gaskell, Charlotte Perkins Gilman (some might start a 20th C reading list with The Yellow Wallpaper), and of course many of the mid-century writers like Elizabeth Taylor, Barbara Pym, Muriel Spark, Iris Murdoch . . . and European authors like Tove Jansson, Selma Largelof, Herta Muller, Elfriede Jelinek, or the young adult fictions of Sonya Hartnett, or the nature writing of Nan Shepherd, or women who write as men like Annie Proulx. And no I haven't even started on the poetry - Carol Ann Duffy, Gillian Clarke, Elizabeth Bishop, Emily Dickinson, Anne Carson, Wendy Cope, Sharon Olds, Dorrianne Laux . . . I could go on (and on) and give you a hundred books, two hundred books in many interesting configurations of theme, genre or subject. What seems clear is that there is no shortage of great women writers but when we get to the place of selection and assessment – reviewers, critics, academics, the marketplace—the people who create and curate the cultural space, the landscape starts to get a lot more tricky.

Reprinted with permission from Writers Hub. Julia Bell is a novelist and Senior Lecturer on the Birkbeck Writing Programme. Find her at www.juliabell.net

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments