In remembering the 'Queen's legacy', why do we forget the suffering of our ancestors?

When news broke of the death of Queen Elizabeth II, international media houses couldn't stop singing her praise and seducing us with the Queen's corgis, her role as a mother and grandmother, her fashion throughout the ages, even a week after her passing.

The most surprising and curious bit however, was how the people of my own nation mourned the late Queen – starting from policymakers to prominent scholars. They posed arguments such as, without the British Empire, the Indian Subcontinent may never have "modernised" as it was indeed the British who had introduced the railroad network that spread swiftly across the subcontinent after 1858. But that remains the only argument they could place to legitimise the crown's authority in the region. Many even said that if it weren't for the British, the Indian Subcontinent would've remained backdated.

I couldn't help but heave a sigh, as these opinions too were a product of colonisation. And it was greatly concerning that as the colonised, we remember so little of our own history, so much so that we choose to make sense of our horribly gruesome past by rationalising the British authority over our region.

To think that the crown had any intention to modernise the Indian Subcontinent is purely ridiculous, as it presupposes that the British Monarchy, that was seeking to consolidate its empire at the time, wasn't acting out of self-interest.

In 1820, India's GDP represented 16 percent of the world's total GDP, which, by the end of the British rule in 1947 stood at just four percent. Revenue from India and the export surplus produced by India's overseas trade were used to fund the British government's military and administrative costs to govern colonial control in India.

Indigo cultivation was widely extended by the British in areas of Bengal, including the districts of Nadia and Jessore. The British indigo planters, known as nilkor sahebs, persuaded the land tillers to cultivate indigo instead of food crops by leasing land from the zamindars, along with sharecroppers and tenants. Opium sales by the East India Company were incredibly exploitative and led to the destitution of over 1.3 million peasants who farmed poppies in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Rajat Kanta Roy, a modern historian, contends that the East India Company's new economy in Bengal during the 18th century was characterised by a type of "exploitation colonialism" that contributed to the collapse of the Mughal Empire's traditional economy by depleting food and currency stocks, and enacting high taxes that exacerbated the famine of 1770, which claimed between one and two million lives in Bengal.

Politician and historian Shashi Tharoor put this circumstance in the simplest terms, "The reason is simple: India was governed for the benefit of Britain. Britain's rise for 200 years was financed by its depredation of India."

Besides, the regiment's self interests are blatantly clear in the way they conducted "trade" with our region. The EIC had forced open the Indian market to British goods, which could be sold in India without tariffs or duties, whereas local Indian producers were still being heavily taxed. Britain's protectionist policies, such as bans and high tariffs to restrict Indian textiles being sold in Britain, made sure that only British wealth would aggregate and be invested into the extraction from the subcontinent. Meanwhile, the Indian subcontinent, slowly and surely became trapped in the empire's monopoly.

Not only that, the rail network, by design, was made for the convenience of the British trade points at the time and had little to do with the commuters' convenience.

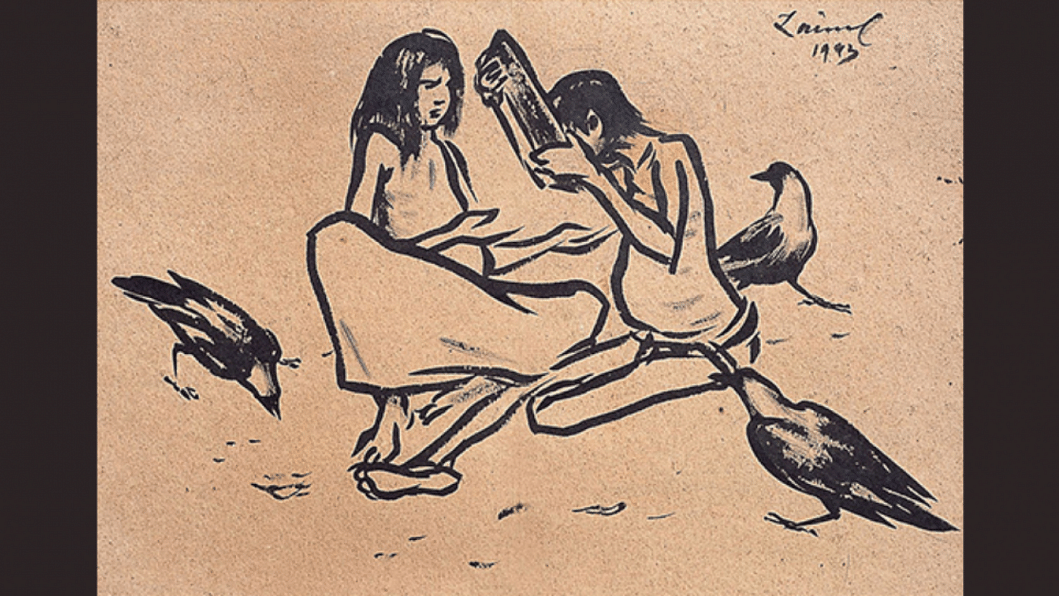

And let's not forget one of the biggest scars left on us by the British – the Bengal Famine of 1943, that took the lives of three million of our people. For years, the British establishment had pointed fingers at frequent droughts and weather conditions of Bengal to have been responsible for this tragedy. In truth, the crisis was constructed and was mostly brought on by wartime inflation that made food unaffordable.

Economist Utsa Patnaik conducted research that showed that the inflation wasn't accidental, as the majority of people believed, but rather the result of a deliberate policy created by British economist John Maynard Keynes and implemented by Winston Churchill to divert resources away from the most vulnerable Indians in order to feed British and American troops and finance war-related activities. And let's not forget, Churchill tried to blame the famine on our ancestors, emphasising that Indians were "breeding like rabbits," and asking how "if the shortages are so bad, Mahatma Gandhi was still alive?"

Might I also add that the way the Indian Subcontinent was divided in a haste by the British, as they were packing up in 1947, had displaced over 15 million people and killed more than two million in the process of migration. And all because the man hired to complete the demarcation – British lawyer Cyril Radcliffe, who was a newcomer in the region – had never visited, nor cared enough about, the history of the regions he divided.

What makes matters even worse is the psychological impact left on the minds of the colonised as an aftermath of the 200 years of British reign. The fact that we automatically associate "beautiful" or "successful" with the fairness of one's skin, was nailed into our heads through British rule. Lest we forget, "Glow and Lovely" was still "Fair and Lovely" until very recently. And, the fact that we prefer foreign products and deem them superior to our locally produced ones is also thanks to an imprint of British colonial rule on our psyche.

So, what can we do about it? The study of decoloniality best serves this answer. In simplistic terms, decoloniality is a school of thought that critiques the perceived universality of Western knowledge and the superiority of Western culture. As a matter of fact, much of the instances discussed in this piece can be attributed to decolonial education. To think and imagine a world beyond the long-established reign of white dominance and perceived superiority.

This education includes bearing an inherent scepticism of what we are told is "truth" and "true knowledge" in the world, which is crucial since much of what we know is constructed via the hands of the ones who had ruled over us. It also emphasises the need of the colonised to remember their own history – to ensure that we don't forget the turmoil that our ancestors went through, to remember that ours is a nation that was thought to be backward, and to never forget that we could've been so much more, if all that we had wasn't looted away from us.

To remember and to be informed are the most important duties that the colonised bear. If we don't fulfil these duties, our own history will be erased and rewritten right before our eyes – and we won't be able to do much about it.

Nazifa Raidah is a journalist and sub-editor at The Daily Star. Reach her at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments