PEC & JSC Exams: Selling ourselves short on accountability

The introduction of the now Primary Education Completion (PEC) (formerly PSC) and Junior School Certificate (JSC) exams have made public schools in Bangladesh more accountable, in a way. A previously under-performing school (by test-score standards) in the remote areas of Khagracchari now reports its pass-rates to the government in a form that allows for an apples-to-apples comparison against benchmarks like the Chittagong board results. In theory, this adds pressure on the school to improve their learning outcomes. However, reality differs from this theory.

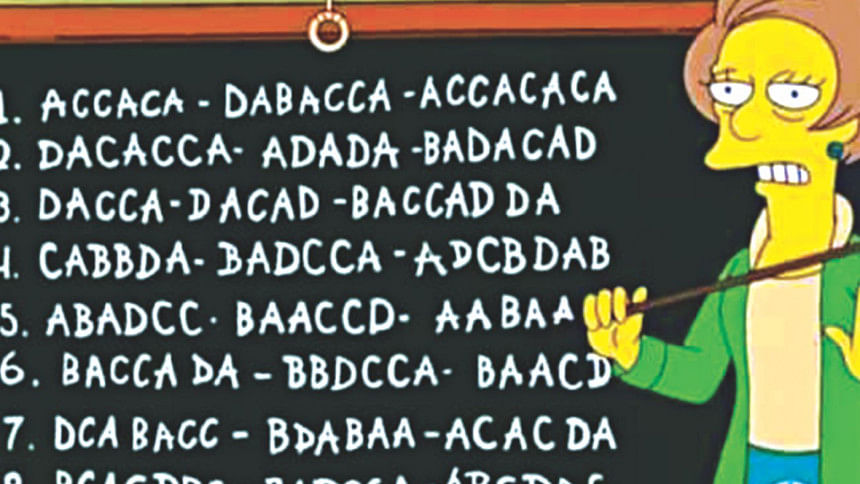

When a school has a 70 percent pass rate in a region with a mean of 95 percent, it can be identified as a candidate in need of additional help and resources. We then supposedly send that school a letter which essentially says, to quote prominent scholar Alfie Kohn, "your test scores are too low, make them go up"—without debating what those numbers mean in the first place. While scores may help with student motivation and public scholarship allocation, their value is diminishing in a world where education is increasingly democratised through open-access technology. On the flip side, focusing on pass-rates gives teachers an incentive to take shortcuts, for example, by making students memorise mathematics (literally), and teach test-taking techniques instead of critical thinking skills, or even manipulate these numbers in some scenarios.

A 2011 paper by economists at Harvard and Stanford on Kenya, where the education system is similar to ours, showed that a focus on test-scores has incentivised teachers to focus on students at the upper end of the achievement distribution, i.e. on those who are likely to increase pass-rates as opposed to those who are struggling. This can not only increase the likelihood of lower-achieving students dropping out of school, but can also neglect these children's potential to attend and succeed in higher education. Many students at or below par in elementary school have gone on to achieve extraordinary things in life, from the likes of Jack Ma to Richard Branson. I suspect we would have more qualified participants in our labour force if we increased the radius of opportunity for students who do not cope well with the current form of formal education in Bangladesh.

Other research by Dr Randall Reback at Columbia University has shown that the US's No Child Left Behind Act in 2002, which attempted to increase school accountability through state-wide examinations, led to undesirable changes in teacher and student behaviour. Our government can learn a lesson here and make changes to a system that currently appears to reinforce the culture of memorisation at the expense of critical thinking. The publicly available National Education Policy 2010 (NEP) document highlights rote learning as a major point of concern. Yet, when I spent some time at a school in Rajendrapur, I could not help but notice that some teachers acted more like drill sergeants than educators. Students ran after guidebooks and "common questions" but were seldom challenged to think for themselves. I suspect that the PEC and JSC has played a big role in exacerbating this issue, as teachers are incentivised to "teach to the test" by asking students to apply formulae rather than understanding them. Since the government is admirably making an effort to rapidly increase access to education, some quality shortfalls are expected. However, if rote learning persists at the formative years of schooling, we risk cultivating life-long attitudes of excessive focus on outcomes—the elusive GPA 5s—and not enough on the process, which is more important when the goal is sustainable and repeated success.

Putting these issues aside, the PEC and JSC exams are poorly administered and have created an environment where public outrage regarding leaked question papers and viral "I am GPA 5" videos are commonplace. In a November 2017 Facebook post, Masud Chowdhury posted photos of his daughter's PEC question paper containing numerous errors. One question read "What is the main cause of destroying natural balance?", while another asked "Why has Bangladesh to import a lot of vegetable oil?" The post received 4,600 impressions, with 1,100 "Haha" reactions as of May 2018. I am unable to fathom what is funny about questions from a national exam containing serious errors. I am also disappointed and surprised that, at the time of writing, not one of the 187 comments in the post asked who was responsible. How do we expect future generations to deliver on dreams of stellar economic growth when we cheat them at such a young age, and do not care enough to advocate on their behalf?

All these issues point to a difficult truth—the model for PEC/JSC exams is not working in its current form, and some changes are needed. USAID's Senior Education Advisor, Shahidul Islam, took a hard stance and called for the discontinuation of the exam in a July 2017 article in The Daily Star. In a December 2016 piece in the Bangladesh Education Journal, he noted that only 30 percent of students performed "at grade level" in basic reading and mathematics, a figure that is in stark contrast to the near perfect (around 98 percent) PEC pass rates. This raises many questions, among them the potential for teacher/grader neglect and manipulation. If incentives for different grading standards and conscious tweaking exist, who is in charge of policing it? As the Roman poet Juvenal asked centuries ago, Quis custodiet ipsos custodes: who will police the police themselves?

The conversation about accountability should stretch beyond schools to policymakers, parents, teachers, and exam writers. We need greater transparency on who gets to decide what is tested, and in what form. The NEP's Section 21 states that the "examination systems will be made more effective". But the questions of how and by what effective means are not stated. While the government's recent decision to scrap multiple choice questions is a step in the right direction, it should be followed up with broader changes, including more specific language in the NEP and, perhaps, new authors and processes for PEC question papers.

Bangladesh is not a resource-rich country—our greatest asset is our people. In a rapidly changing world where our cheap-labour driven economy is already facing headwinds, the emphasis on independent thinking should be amplified. We must take steps towards a knowledge-driven economy with a dynamic workforce, with people who can think for themselves and have skills that cannot be replicated by machines. Pass-rates can only take us so far.

Sakib Jamal is a third-year undergraduate student at Cornell University's School of Industrial & Labor Relations, New York.

Email: [email protected]

Comments