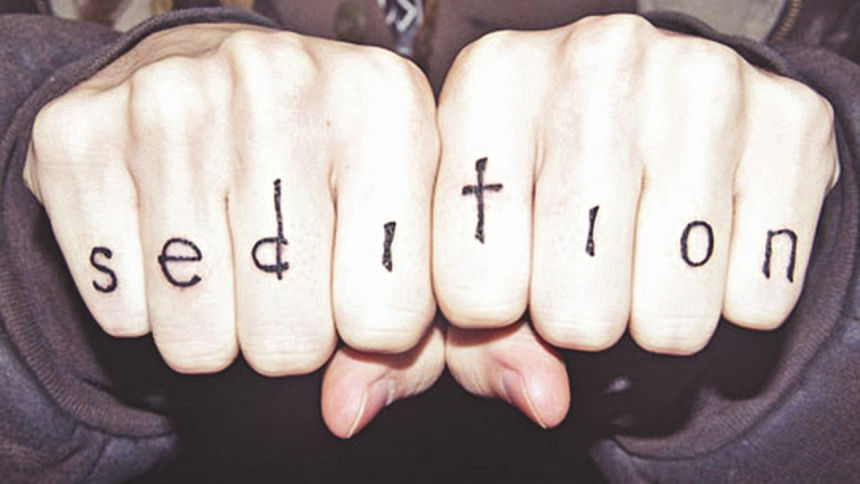

Sedition is too old fashioned in a modern society

THE right to freedom of expression is crucial in a democracy – information, criticism and ideas help to develop democratic political environment and are essential to public accountability and transparency in government. Universal declaration of human rights was asserted in the Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh which gives everyone the right to freedom of expression, including freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without State interference (Article 39). Freedom of expression goes to the heart of the natural right of an organised freedom-loving society to impart and acquire information about things which attract our national interest. This right was achieved through our war of independence in 1971.

Recently more than 12 sedition cases were filed against The Daily Star editor Mahfuz Anam. In those cases Mr. Anam is alleged to have committed the offence of sedition by publishing news reports on his highly circulated national English language paper The Daily Star about Prime Minister Shiekh Hasina during the controversial 1/11 period, which Mr. Anam has recently acknowledged as one of his greatest mistakes in his editorial career since the reports were not independently verified. This has come into light once again when Mr. Anam purportedly admitted in a TV interview broadcasted prior to the 25th anniversary celebration of DS. Published reports, as acknowledged by Mr. Anam, were based on the information supplied by the intelligent agency (DGFI) without the DS independently verifying them.

These recent cases filed across the country brings to the fore the issue of whether most of those sedition cases fall within the scope of the relevant law. Sedition is well defined and codified in the Penal Code. Section 124A of the Penal Code states: "Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards, the Government established by law shall be punished with imprisonment for life or any shorter term, to which fine may be added, or with imprisonment which may extend to three years, to which fine may be added, or with fine". The most important ingredient needed to be found in order to charge or convict someone for sedition is that he brings into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards, the Government established by law. Sedition contemplates that degree of dissatisfaction, hatred or contempt which induces people to refuse to recognise the government at all and leads them to unconstitutional method. The High Court Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh held in many cases that prosecution, in order to prove someone guilty of sedition, has to establish by evidence that the accused brought the government into hatred encouraging dissatisfaction. It means spoken or written words, sign or representation must be directed to excite or attempts to excite disaffection towards the Government established by law. Since the leader in question was not in power when the alleged reports were published in the newspaper, the question of exciting or an attempt to excite to create dissatisfaction or any bad feelings or to bring hatred towards the government does not arise. The cases filed throughout the country lack basic or the most essential elements in order to find someone guilty of sedition even if the allegation is taken in its entirety as true and given the most negative interpretation, amounts to the offence of sedition as it is defined in the penal code, there is simply no way in which any conduct of Mahfuz Anam can be treated as seditious.

The law on seditious libel originated from English law. In England, a seditious libel is a statement which brings into "hatred or contempt" the monarch, her heirs, the government or its officials. Proving the truth of any statement which causes this "hatred or contempt" is no defence against charges of seditious libel. But Halsbury sets a higher threshold that the essence of the offence of treason lies only in the violation of the allegiance owed to the sovereign. These common law principles evolved from some of Britain's oldest laws, such as the Statute of Westminster 1275, when the divine right of the king and the principles of a feudal society were not questioned. Seditious libel was established by the Star Chamber case De Libellis Famosis of 1606. Not only was truth no defence, but intention was irrelevant. Criminal libel and seditious libel laws were used extensively in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, perhaps most famously against the renegade MP and civil rights campaigner John Wilkes, whose publication North Briton was declared a seditious libel and publicly burned. In the twentieth century however, as British democracy evolved and liberalised, the number of prosecutions for these offences declined sharply. The last decade to have seen any prosecutions for sedition was the 1970s.

Recently, the UK Parliament abolished outdated offences of seditious libel and criminal defamation which used to restrict freedom of expression, thoughts, conscience and democratic values setting up examples for the other countries. The current leader of the opposition labour party Jeremy Corbyn, a socialist democrat, refuses to bow before the monarch and sing the national anthem of UK, alleging that it praises the monarch. However, no charge of sedition was brought against him. The UK Supreme Court (previously known as the House of Lords) in many decisions, confirmed that rights as granted under Article 10 of the ECHR cannot be restricted in any circumstance unless it conflicts with other rights guaranteed in the ECHR, or it is in national interest or security of the state required it to be restricted.

It is a well settled principle in modern jurisprudence that mere criticism of actions and policies of the government, even though harsh in nature does not attract any offences of a seditious nature. Even the explanation 2 to the section 124A of the Penal Code makes it clear that criticism of public measures or comment on governmental action, however strongly worded, within reasonable limits and consistent with the fundamental rights of freedom of expressions, should not be affected rather it ensures accountability and transparency of the government.

Article 39 of the Constitution of Bangladesh guarantees the right of every citizen to freedom of speech, expression, freedom of the press, freedom of thought and conscience subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interests of the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence. Freedom of expression as guaranteed in our Constitution can only be restricted when it undermines national security, risks public interest and/or undermines other persons inalienable human rights as also guaranteed in the constitution.

Nevertheless, any attempts to use Section 124A of the penal code to restrict journalists, civil society or even the ordinary citizen of the country, is simply outrageous and too old fashioned and should not have any place in modern society. Circumstances have changed since the incorporation of Section 124A (sedition) in the penal code and they are changing with the advancement of modern times when criticism of the government has become the basic foundation on which democracy is built. Freedom of speech and media ensures transparency and makes the government accountable in discharging its duty towards its real master, the people. Freedom of expression is important not merely as an irritant to the state, though that function is surely a key aspect of democratic life. Journalists, publishers, bloggers and NGOs are citizens with the capacity to highlight issues of concern, and to propose solutions. When their right to speak freely and frankly is curtailed, either directly by the state or indirectly by the threat of disproportionate civil action, so is their ability to underwrite the fundamental rights and freedoms of their fellow citizens.

The writer is Barrister-at-Law, Honorable Society of Grays, Lecturer of London College of Legal Studies (LCLS, South), and an

advocate. Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments