Cold, killing design

The rumble of a diesel engine broke the silence of the chilly morning of December 14, 1971, at teachers' quarters on the Fuller Road in Dhaka University.

A minibus of East Pakistan Road Transport Corporation, smeared with mud, stopped there around 8:15am. A group of six to seven people got off the bus, all armed. They climbed straight to the third floor and rang the doorbell of flat 16-H.

"Is it the home of Serajul Haque Khan," gently asked one of the two standing at the door in clear Bangla. The others stood behind them in the staircase.

"Yes," replied Serajul's younger brother Shamsul Haque Khan nervously.

"Is he inside?" was the next question.

Perplexed Shamsul replied, "He is on the ground floor ... at Dr Ismail's home."

The men then went down to the ground floor. Within a few minutes, they took Serajul out of the flat and dragged him to the minibus blindfolded.

Serajul Haque Khan, an assistant professor of Institute of Education Research of Dhaka University, never returned home like the scores of brightest and illustrious citizens, who were rounded up in similar fashion, tortured and killed just days before Bangladesh was liberated.

Sensing imminent defeat, the Bangalee collaborators, particularly the Al-Badr, executed the Pakistan army's blueprint to eliminate teachers, writers, doctors, lawyers, journalists and other professionals. This final act of atrocity was carried out to destroy the future of soon-to-be born country, to maim the nation permanently and rob it of its brightest minds.

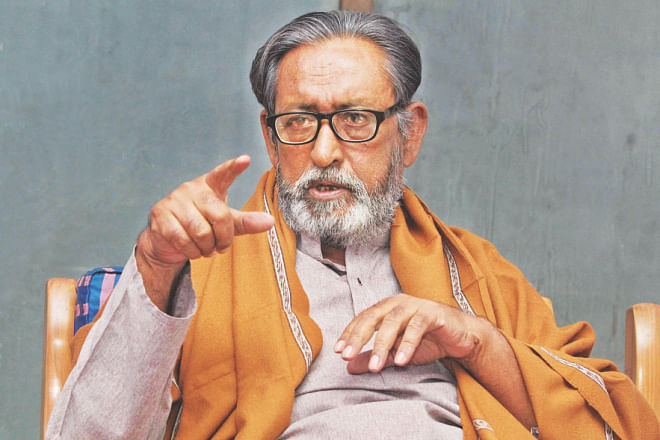

Forty-three years after the acts of cold-blooded savagery, a son of Serajul thinks the vacuum left by the killing of intellectuals is yet to be filled.

"I think the killers have been successful to some extent. They created a vacuum at all levels of our national life. We are still struggling to fill the vacuum even after so many years," said Enamul Huq, Serajul's son.

The eldest among eight siblings, he saw his father's abduction happen and shared it with The Daily Star at his Khilgaon home.

He said his father was a believer of Bangalee nationalism and was a progressive man.

"Being a teacher of the education administration, he used to speak against the discriminatory education policy of the then Pakistan government. The ruler considered his actions as a threat to the national integrity of Pakistan," said Enamul, now a history professor at Jahangirnagar University.

"For these reasons, I think, my father became the target of the Pakistan army and their collaborators."

In fact these were the common reasons for the massacre of the intellectuals, he said.

Prof Munier Choudhury, Muffazzal Hyder Chowdhury, Shahidulla Kaiser, Selina Parveen, Abdul Alim Chowdhury and many other illustrious citizens met the same fate like Serajul.

And their fault was that they encouraged and seeded the idea of nationalism through their work, writings and activities, and helped freedom fighters during the war.

The local agents of the Pakistan army provided the information about the intellectuals. The Pakistan army formed special forces -- Al-Badr and Al-Shams, which carried out the systematic killing, said Enamul, who was the pro-vice-chancellor of JU from 2003-2007.

Almost all members of the forces, especially Al-Badr, were educated and well-aware of progressive citizens and their activities, he said.

Al-Badr was formed with the leaders and activists of Islami Chhatra Sangha, the then student wing of Jamaat-e-Islami, the party that fought tooth and nail to thwart the birth of Bangladesh, according to historical documents.

Sixty-seven-year-old Enamul still vividly remembers the morning of December 14, 1971.

"I saw from the balcony that they blindfolded my father with his handkerchief and dragged him to the minibus," said Enamul, then a final year student of Dhaka University.

On that morning, they came to know that six other DU teachers and a physician of DU medical centre were abducted from the campus in similar fashion. They were: Giasuddin Ahmed, Anwar Pasha, Rashidul Hasan, Faizul Mahi, Abul Khair, Santosh Chandra Bhattacharyya and Mohammad Martuza.

Enamul's family could not look for Serajul that day because of the curfew that was enforced.

As soon as the curfew was over, following the surrender of the Pakistan army on December 16, Enamul, his friends and his father's colleagues hired a vehicle to look for him and other abducted intellectuals.

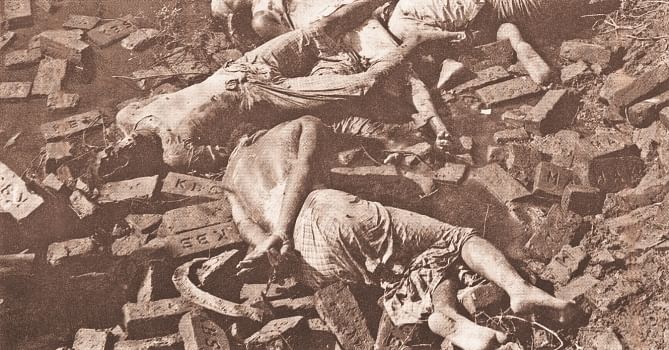

"We first went to the Mohammadpur Physical Training College and then to Rayerbazar killing field. I searched for my father among the dead bodies," he said.

"I left no stone unturned. For two weeks we searched almost all killing grounds in Dhaka city and its surrounding areas. I even rushed to a river in Fatullah hearing about dead bodies floating there, but I didn't find him," he said.

The family started losing hope until NSI official Sattar, who was the classmate of his father, went to their home with Mafizuddin in January, 1972. Mafizuddin was driving the minibus for Al-Badr that picked up the intellectuals from the university campus.

Seeing photographs, Mafizuddin identified the people abducted and put inside the minibus he drove. He told Enamul what had happened afterwards.

"The abductors took them straight to Mirpur Lohar Pool (near Gabtoli) with the plan to shoot them dead and dump the bodies in the Turag river," Enamul quoted Mafizuddin as saying.

But they could not do so as Razakars and other collaborators also assembled many Bangalees there to kill, he said. Making a U-turn, they started travelling on Mazar Road and stopped before a graveyard in Mirpur, where the Martyred Intellectuals' Memorial was built after liberation.

"The abductors walked them to the graveyard until they reached a paddy field and shot them dead," said Enamul quoting Mafizuddin.

Following Mafizuddin's lead, eight bodies were exhumed from the graveyard.

"I identified my father's body with his belt and the Italian gabardine trousers. I also found his identity card in his pocket," he said, adding that the families of the other intellectuals also identified their loved ones.

The brutality of the Pakistan army and their collaborators and the clinical way they carried out the killings of the intellectuals started unfolding after Victory Day 1971.

Newspapers, including Dainik Purbadesh, ran reports on it and published the photographs of many of the killers, including Al-Badr kingpins Chowdhury Mueen Uddin and Ashrafuzzaman Khan, with the caption "help capture the killers of intellectuals".

"I saw the photos in Purbadesh and identified the smart two youths, who came to our home to pick up my father on that morning [December 14]. They were Mueen and Ashraf," Enamul said.

Al-Badr men started rounding up and killing professionals from the second week of December. However, there was no specific government list of martyred intellectuals.

On December 22, 1971, Dainik Azad published a report quoting Indian radio channel Akashbani news where Ruhul Quddus, then secretary general of the Bangladesh government, had said at least 280 intellectuals and professionals were killed on December 14 and 15 in four areas -- Dhaka, Sylhet, Khulna and Brahmanbaria.

According to Banglapedia, around 991 academics, 13 journalists, 49 physicians, 42 lawyers and 16 others were savagely killed during the war.

Only on February 7 this year, the Awami League government announced that it would publish a comprehensive list of all the martyred intellectuals by June this year.

Liberation War Affairs Minister AKM Mozammel Haque had made the announcement during a parliament session, but no such list was published.

Time elapsed and the agony of the justice seekers continued until the formation of the International Crimes Tribunal in March 2010. The tribunal last year began trial against Chowdhury Mueen and Ashrafuzzaman in absentia for the killing of 18 intellectuals.

Like many other martyred intellectuals' children, Enamul testified in the case. "Initially I thought of not testifying. What would it yield after so many years? But later I thought it was my national duty and I testified," Enamul said.

The Tribunal-2 sentenced Mueen and Ashrafuzzaman to death. Mueen is now staying in the UK while and Ashrafuzzaman in the USA. Experts believe it was almost impossible to execute the verdict because bringing the duo home was difficult. A monitoring cell was formed to bring them back but it made little headway in this regard.

But Enamul does not think so. "I have doubts over the government's sincerity to bring them back home."

Jamaat leaders Motiur Rahman Nizami and Ali Ahsan Mohammad Mojaheed, who were the top leaders of Al-Badr, were also awarded death penalty by the tribunals for planning the killing of intellectuals. They have appealed to the Supreme Court.

On the eve of Martyred Intellectuals' Day, Enamul expects little from the country his father gave his life for.

"We don't want anything from personal level or family level. We only want to see the dreams and objectives of Liberation War fulfilled," said Enamul, staring at his father's photograph on the wall of his living room.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments