Book Review

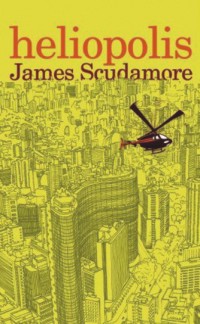

Heliopolis

Sinclair Mckay

Heliopolis broadly, “City of the Sun” is a brightly ironic title for a dark, gripping, often comic novel concerning appetite, urban poverty and identity. Heliopolis is a slum district in the mega-city of São Paulo.

In James Scudamore's vision, this mega-city is reminiscent of Fritz Lang's 1926 film Metropolis: the rich live high above the ground in luxury skyscrapers, their aircraft buzzing around the skyline, while the poor are huddled in the filthy dark below.

Our young protagonist Ludo knows the city better than most; he and his mother were plucked from these seething slums when he was small, by the socially concerned wife of a rich businessman, Ze Carnicelli. Ludo's mother has now become Ze's family cook out on the country estate. And Ludo, who grew up on that estate, is now a young man who works for a marketing firm back in the city, this time living among the rich.

From the start, the character seems prone to odd spasms of self-destructiveness that give this book its irresistible narrative pull. At the start, we learn that Ludo is obsessively smitten with his adoptive sister Melissa, who is not un-encouraging, and insists on assignations in her marital home, even though there is the ever-present danger of her husband (or worse, father) walking into the penthouse apartment unannounced. Ludo not only reads the husband's computer diary, but also makes changes to the text. He leaves messages written on the bathroom mirror. When out on the streets of the city, this propensity for living dangerously leads to an appalling gun incident involving a teenager that eventually comes to threaten the balance of Ludo's life.

Ludo is a man of sharpened appetites, which are also central to the novel. Carefully prepared food is, for him, as much about emotional resonance as sensual gratification, which seems to have been the case since his upbringing in the country. There is a flashback to his childhood on Ze's country estate with Melissa; and the way, Estella-like, she began to entice him. Indeed, in another slight parallel with Great Expectations, Ludo is gradually given cause to doubt the source of his good fortune, just at the point when his two worlds the slums from which he came and the rich gated communities that he now moves in look set to collide.

Mixed in with all this is some compelling social satire concerning the latest scheme of Ludo's adoptive father, Ze: that is, to adapt his lucrative supermarket chain and start opening outlets in the slums, areas in which no shops at all have previously ventured. It is up to Ludo's marketing agency to find a strategy to sell such an idea to the slum dwellers. It is only Ludo who understands precisely the problems they might be storing up, and by the end all the different strands of the novel are pulled together in a hugely satisfying way.

Underpinning the novel are questions of survival and indeed of identity. The rich cannot imagine how the slum poor must live; yet through our guide Ludo, who towards the novel's climax gets lost in those fetid streets, we are shown not Child of the Jago-style masses, but well-drawn people simply getting on with their lives as best they can. Even the feral teenagers are not entirely what one would expect. The constant undercutting of the reader's expectations which are not so far from those of the São Paulo rich is at once sly, amusing and illuminating.

And there is also an engaging theme concerning the indomitability of identity; that one can have one's circumstances, one's life, wholly changed and yet stubbornly remain exactly the same person. Ludo's impulses and outbreaks of self-hatred are a compulsion to allow his true self proper sway. He embodies a city versus country conflict in an unusually direct way.

Scudamore has the superb novelist's gift for giving vivid, sympathetic life to even second-string characters, as well as his main ones; and he also has the extraordinary power of summoning an entire brooding, smoggy city to life.

Most of all, though, he has the ability to take on the heaviest of themes with the lightest and most compelling of touches, and leave you with an appetite for more.

This review first appeared in The Telegraph.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |