|

Cover

Story

Perils on Dhaka Roads

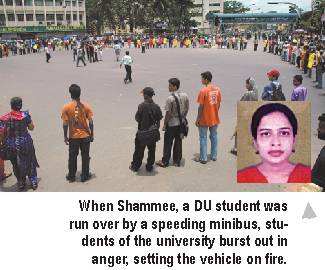

Death counts on Dhaka's roads have reached unbelievable levels lately. The recent death of Shammee Akhter, a university student who was hit by a speeding minibus violating a traffic signal and many others before that, only testifies just how dangerous the city's roads have become. Invariably, it is a hit and run case or one in which the driver is never found. With more and more reckless drivers, unfit vehicles plying the streets and a burgeoning population within the city's perimeter, it is not surprising that gruesome accidents have become an everyday affair. But there are many more reasons for such avoidable tragedies. Lack of walking space, inadequate road space and the absence of enforcement of traffic rules and even irrational pedestrian behaviour can be attributed to road accidents. But most of all, the complete apathy of the authorities to enforce laws and bring about a semblance of order to the city's mad traffic, has led to higher numbers of unnatural deaths on Dhaka's brutal streets. Death counts on Dhaka's roads have reached unbelievable levels lately. The recent death of Shammee Akhter, a university student who was hit by a speeding minibus violating a traffic signal and many others before that, only testifies just how dangerous the city's roads have become. Invariably, it is a hit and run case or one in which the driver is never found. With more and more reckless drivers, unfit vehicles plying the streets and a burgeoning population within the city's perimeter, it is not surprising that gruesome accidents have become an everyday affair. But there are many more reasons for such avoidable tragedies. Lack of walking space, inadequate road space and the absence of enforcement of traffic rules and even irrational pedestrian behaviour can be attributed to road accidents. But most of all, the complete apathy of the authorities to enforce laws and bring about a semblance of order to the city's mad traffic, has led to higher numbers of unnatural deaths on Dhaka's brutal streets.

Shamim Ahsan with Mustafa Zaman, Imran H. Khan and Elita Karim Shamim Ahsan with Mustafa Zaman, Imran H. Khan and Elita Karim

As Abdul Wahab, one of the many commuters who regularly take the local bus from Kalyanpur to Karwan Bazar or Motijheel, saw the double-decker approach, he heaved a sigh of relief. It was the only alternative to squeezing oneself into a mini-bus. He got on the bus with the others. Even though all the seats were already filled out it did not irk him, he was quite comfortable standing. But little did he know that 10 to 15 minutes later the same bus would run into a fatal accident in which an elderly woman would be crushed under its wheels.

For every bus driver, Manik Mia Avenue seems to be the ultimate racing ground to drive as recklessly as possible; past Asad Gate intersection they all pick up speed. The bus that Wahab was in also did the same. It was at the end of the avenue near the roundabout at the other end that it suddenly steered to the left. At first Wahab thought that the driver had lost control. But then, the immediate thud of the bus hitting something hard made him realise that it had collided with another vehicle.

Finally when he followed the others, the shattered mini-bus that the double-decker hit and pushed along with it was in sight. Most passengers of the bigger bus had escaped without a scratch but the ones in the min-bus were not that lucky. The most devastating realisation on the part of the passengers who were unharmed was that an elderly woman had fallen out of the smashed window of the minibus and had landed on the tarmac. And after the accident she was discovered with half of her body underneath the rear wheels of the double decker. With the driver absconding, the passengers quickly got into action; they started to push the bus in the opposite direction. And after stopping a CNG-run scooter took her off to the nearest hospital. Finally when he followed the others, the shattered mini-bus that the double-decker hit and pushed along with it was in sight. Most passengers of the bigger bus had escaped without a scratch but the ones in the min-bus were not that lucky. The most devastating realisation on the part of the passengers who were unharmed was that an elderly woman had fallen out of the smashed window of the minibus and had landed on the tarmac. And after the accident she was discovered with half of her body underneath the rear wheels of the double decker. With the driver absconding, the passengers quickly got into action; they started to push the bus in the opposite direction. And after stopping a CNG-run scooter took her off to the nearest hospital.

This does not happen every day. But a report on accidents published by The Daily Prothom Alo portrays a harrowing picture, it put the death toll at 11,000 in the last three and a half years.  Death counts on Dhaka roads are on the rise. With inter-district buses and trucks plying on the main roads, the likelihood of fatal accidents have increased. On September 6, 2004, Zakia Sultana, a student of first year of the Dept of Philosophy in Jahangir-nagar University fell victim to a speeding bus while she was waiting for one to go to Dhaka. Her death was followed by an immediate backlash. One hour after the accident, angry students disrupted the traffic flow for hours, clashed with the police, broke 10 buses and even burned down 10 or so road-side shops. Death counts on Dhaka roads are on the rise. With inter-district buses and trucks plying on the main roads, the likelihood of fatal accidents have increased. On September 6, 2004, Zakia Sultana, a student of first year of the Dept of Philosophy in Jahangir-nagar University fell victim to a speeding bus while she was waiting for one to go to Dhaka. Her death was followed by an immediate backlash. One hour after the accident, angry students disrupted the traffic flow for hours, clashed with the police, broke 10 buses and even burned down 10 or so road-side shops.

For any driver, after the accident, the first move is to flee the scene. The fear of losing one's life is not unfounded. The mob is always ready to beat the driver up without giving much thought to whose fault it was in the first place. However, one can easily conclude that on most occasions, it is reckless driving that causes the accident. The recent incident at the Shahbagh intersection that took the life of Shammee Akhter, a third year student of psychology and resident of Rokeya Hall, testifies how the speed demon has cost us dearly. Shammee died when a minibus ran her over while trying to jump a traffic signal. The bus crushed her and injured several others. Shammee died on the spot. Two other victims who were critically injured are struggling for their lives.

Shammee's death sparked off a violent reaction from the DU student community. Students clashed with police for more than three hours. The protestors set fire to the bus and damaged about 20 vehicles on the road. The police fired rubber bullets and teargas shells and charged batons to disperse the agitated students. They even transgressed the campus of the Instititute of Fine Arts and broke into exam halls to beat up examinees. At least 10 students were admitted to the Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH) and 50 others to different private clinics says a report in The Daily Star. It is almost a repetition of the violence that ensued last year after the death of Sultana of Jahangirnagar University. The frustration and anger in the face of the inaction by the authorities have only been magnified and, as a result, the situation got out of control.

Each death of a student pitches the students of a particular college or university against the police force. But in the end the steps that might curb the reckless driving, or the measures that will make Dhaka's roads safe are never drawn out.

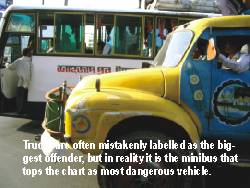

Road safety as a concept has received little attention both by the authority and by the public. In the collective consciousness, trucks constitute the most dangerous vehicle that ply the roads, as there have been a lot of accidents involving the cargo transporter. Somehow, commuters, traffic police and drivers of other modes of vehicles appear to be in perfect consensus when it comes to blaming truck drivers for causing most accidents. Abdur Rashid, a truck driver from Dinajpur, doesn't accept this allegation, "Trucks might be involved in some of the accidents that occur in the highways, but not in the city. We cannot get in the city before 10 pm, how can we be responsible for most accidents?" Road safety as a concept has received little attention both by the authority and by the public. In the collective consciousness, trucks constitute the most dangerous vehicle that ply the roads, as there have been a lot of accidents involving the cargo transporter. Somehow, commuters, traffic police and drivers of other modes of vehicles appear to be in perfect consensus when it comes to blaming truck drivers for causing most accidents. Abdur Rashid, a truck driver from Dinajpur, doesn't accept this allegation, "Trucks might be involved in some of the accidents that occur in the highways, but not in the city. We cannot get in the city before 10 pm, how can we be responsible for most accidents?"

Rashid, who claims to have a clean record in his eight-year-long career, identifies what he believes to be the real reasons of accidents: "Drivers who are young and have just sat behind the wheels sometimes lose control out of nervousness. Sometimes they tend to drive fast because of their hot-bloodedness and cause accidents." A strong defender of his compatriots, he denies the allegation that truck drivers cause accidents because they drive drunk. "People of every profession have bad habits. Rickshawpullers also smoke ganja, heroine, etc. Some truck drivers might have this habit, but they never drive after drinking," he claims.

Rashid, however, admits that truck drivers sometimes cause accidents because they fall asleep while driving. "We have to drive days and nights. Sometimes we are very sleepy, but continue to drive thinking that we will sleep after we reach a certain place. Most accidents involving trucks occur because of this. One should just take the truck aside and sleep when he feels like sleeping," he believes. According to Rashid, minibus drivers are the worst drivers, "They will get into a gap where even a needle cannot enter."

Statistics support Rashid's view. A recent Dhaka Metropolitan Police (DMP) survey shows that trucks are way behind buses in causing accidents. Among a total of 594 accident cases filed with 22 police stations in Dhaka in 2004, buses caused 297 while trucks were responsible for 93. The survey identified minibuses as the biggest culprit -- they caused 157 accidents in which about 350 people died and 221 were severely injured.

The reason is, as Bangladesh Road Transport Association (BRTA) motor vehicle inspector Ashrafuzzaman points out, "A large number of the minibuses are not fit for plying the streets." The reason is, as Bangladesh Road Transport Association (BRTA) motor vehicle inspector Ashrafuzzaman points out, "A large number of the minibuses are not fit for plying the streets."

Some 3,000 minibuses ply on 98 routes in Dhaka. According to a Dhaka Road Transport Authority (DRTA) official, when minibuses were introduced in 1981, usually reconditioned minibuses were brought from Japan. Though they should have long been forced off the roads they are still in service after rounds of repair and re-repair.

DRTA, the government agency responsible for overseeing various aspects related to transport, is certainly not doing a great job. They however have their arguments regarding their failure to bring order in the transportation sector.

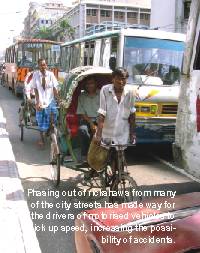

Apart from issues like lack of fitness, fakes licences and untrained drivers, there are also the more basic limitations that cannot be solved overnight, Inspector Ashrafuzzaman points out. "A city has to have roads that are 25 percent of the city's entire area, whereas Dhaka has got even less than 10 percent. The number of vehicles are simply too high for any system to work," he says. Ashrafuzzaman then identifies another cause for accidents: "When motorised and non-motorised vehicles ply side by side, there is bound to be trouble if the drivers of the motorised vehicles are not extremely cautious." He then gives the instance of Gabtoli-Science Laboratory road where the accident rates are declining after the road was made off limits to rickshaws.

As to the question of unfit vehicles, only a year back, the sitting Communication Minister declared jihad against buses and minibuses that had been in operation for more than 20 years. Many of the aging buses were caught by the sergeants while many others went into hiding. But the minister's enthusiasm declined and the old buses staged a comeback with a new look. With these ancient, absolutely unfit buses, Dhaka's streets continue to be as hazardous as ever.

Fitness is not the only thing lacking. Many of the bus or minibus drivers do not have licence or have fake ones. It is even easier to obtain a fake licence. A fake plastic card costs around Tk 1,000 and one could get away with most misdemeanors. If one wanted the genuine licence, then he/she has to pay Tk 5,000. This process is indirectly done through BRTA, many claim.

There are no specific statistics regarding how many drivers have got fake licences. The percentage ranges from anywhere between 40 to 60. While ASM Ahmed Khokon, treasurer of DRTA, puts the figure of fake licence holders as high as 60 percent, traffic Sergeant Sohel Arman (not his real name) under Dhanmondi police station, believes the figure would be less than 40 percent. There are no specific statistics regarding how many drivers have got fake licences. The percentage ranges from anywhere between 40 to 60. While ASM Ahmed Khokon, treasurer of DRTA, puts the figure of fake licence holders as high as 60 percent, traffic Sergeant Sohel Arman (not his real name) under Dhanmondi police station, believes the figure would be less than 40 percent.

Thirty-year-old Tareq Hossain, a minibus driver on Sayedabad-Gabtoli route, admits that many of the drivers carry fake licences. It's a great hassle to obtain an original one. You have to go to the BRTA office a hundred times, pay Tk 6,000 to Tk 7,000, sit for a test, and face an interview before you get an original license," Hossain says.

Bangladesh Road and Transport Authority (BRTA) has simplified this process to the extent that one simply needs to pass through five simple tests and you become the proud owner of a genuine licence. There are people who choose the easier way they go for the fake licence.

The driver's licence tests include a written test, a viva and three field tests. They are the Zigzag test, the Ramp test and the Road test. The written and viva are taken in various locations but the final three field tests must all be done at Mirpur 13, amidst the glaring eyes of hundreds. The licence costs for a Learner is Tk 200 and then after the test, a Professional category licence costs Tk 650 and a non-Professional category licence costs Tk 1150.

As for fitness tests, often all ones has to do is carry the tin certificate and six to seven hundred taka and go to the BRTA office.

Fayaz, who had completed the fitness test for his two-year-old Toyota, feels that there are a lot of loopholes one can exploit. "Even before you enter into the BRTA compound, there are people around who will be able to advise you on how to get the fitness tests done with the greatest ease," says Fayaz. These consultants usually have some inside people to help them. Once inside the compartment, the picture is pretty much the same. A fitness test to be done in a legal way, entails running around from counter to counter, filling in endless documents and papers. A simple bribe would be able to go a long way to filling up one's 'legal documents'. Within minutes, your fitness test would be complete.

One has to be careful, though, to make sure that you have all the right documents. If there are problems with the car or the papers, one has to pay extra bribe to get the job done. It's an open secret. "I had to pay about Tk 700 because I didn't have a TIN certificate," continues Fayaz. Because of this certificate, he had to pay Tk 300 for the missing document and a little extra to make sure that the process is faster, but nothing hinders the fitness process.

"A funny thing is that nowadays, you do not even need to take your car to have a fitness test done. All you need are the right papers and some money for 'processing'. If you pay the right people, everything will be taken care of," concludes Fayaz.

About the real test, Fazlur Rahman, a Fitness Inspector for BRTA, gives a little detail on the criteria. "The main things in question are the identification numbers of the engine and the chassis. The other things that are looked at are the external features of the car, the seats and the lights. After running the engine, the brakes are tested and the car is checked for black smoke," says Rahman. The cost of doing a fitness test, the duration of which is for a year, is Tk 645 for a light vehicle, such as a private car. For heavy vehicles, such as buses and trucks, the cost is Tk 945. The fee goes to the government. The duration for a fitness test is one year, and if the fitness date runs out, one has to pay a monthly fine of Tk 150. About the real test, Fazlur Rahman, a Fitness Inspector for BRTA, gives a little detail on the criteria. "The main things in question are the identification numbers of the engine and the chassis. The other things that are looked at are the external features of the car, the seats and the lights. After running the engine, the brakes are tested and the car is checked for black smoke," says Rahman. The cost of doing a fitness test, the duration of which is for a year, is Tk 645 for a light vehicle, such as a private car. For heavy vehicles, such as buses and trucks, the cost is Tk 945. The fee goes to the government. The duration for a fitness test is one year, and if the fitness date runs out, one has to pay a monthly fine of Tk 150.

There are many reasons associated with road accidents. Shameem Sharker, a local businessman, feels that the two prime reasons are speeding and driving non-stop. The Motor Vehicle Ordinance of 1983 states that a person can drive for at most five hours at a stretch and then rest but that does not apply here at all. "Drivers are on the road for even 10 hours at a stretch and without rest. It is natural for a person to lose control after that," states Sharker. Absense of bus-boys is another reason for accidents. And often the passengers crowd the roadside, endangering their own lives. Not having bus-boys and earmarked bus stops lead to the drivers stopping their vehicles wherever they please, and this erratic practice sometimes leads to tragedies.

Stress is also being associated with many road accidents. Driving has become a tiresome, stressful activity with lack of any kind of driving etiquette on the roads and people frequently deciding to cross the road all of a sudden without seeing if it is safe or not.

The tendency among the drivers of the same route to lock in a race makes roads perilous. Most regular bus passengers know this. " Whenever two buses of the same route get closer they start a race, dangerously picking up speed and overtaking rickshaws and cars," Shafiqur Rahman, a middle-aged Dhaka Bank official alleges.

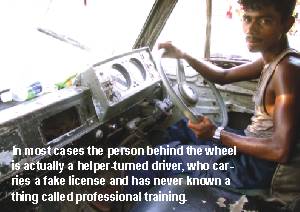

Just one ride in a minibus gives one a fair idea about the driver's knowledge of traffic rules as well as his training. Most bus and truck drivers in the country do not go to any training schools, but learn it practically from their ostads.

"All these bus and truck drivers are actually helpers-turned-drivers, they start to learn after they actually start driving," says Ruhul Kuddus, general secretary of Jatiyatabadi Dhaka Inter-city Bus Owners' Association.

But why do the owners employ such drivers? "Where will you get so many drivers? Good, experienced drivers who have got original licences do not want to drive buses and in case you get anyone of them they demand too high a pay," he explains.

As drivers are underpaid, their service too remains below any acceptable standard. In absence of any regulatory body, other than the bribe-guzzling traffic sergeants, drivers remain impervious to passengers' insistence on driving slowly. Drivers go by their own rules. Tareq Hossain, the young minibus driver on Sayedabad-Gabtoli route, explains why they are always in a hurry: "If I can go past a bus of my route I will get the passengers waiting at the next stop. If I don't get enough passengers on board I won't be able to gather my joma (the amount which a driver has to pay to the owner)." Usually bus drivers don't have any fixed pay. The system is, a bus driver has to pay a certain amount to the owner and the rest, whatever the amount is, goes to the driver and the helper. So a driver tries to make as many trips as possible and with as many passengers as possible.

"On the Sayedabad-Gabtoli route we can usually make five trips, sometimes four (One trip is equal to travelling the entire distance -- from Sayedabad to Gabtoli -- twice) and after paying Tk 1500 as joma we earn around 300 to 400," he explains.

More trips mean more income and it is this equation that seems to matter to these drivers, nothing else. And they would do anything overtaking other vehicles from the left hand side, cross the yellow line, not slowing down at the speed breakers, stop anywhere to pick up a passenger and of course, drive crazily fast -- to push the trip number from five to six, absolutely unaware of the risk they are running against. The bus owners support this pay system instead of a fixed monthly salary.

"If their salary is assured they won't bother about how many passengers they have got or how many trips they have made. But when there is a ceiling he knows he can earn a lot if he works hard," Kuddus explains the rationale behind this payment system.

And in the streets of Dhaka a driver can afford to be as unruly and indisciplined as he wishes to be. It doesn't matter if he is absolutely ignorant of the traffic rules and goes on continuously violating them; neither does he have to have a valid licence; he can defy the red light and pick up more speed than allowed. Because he knows he can get away with anything. Traffic sergeants are sometimes a worry, but not big enough if the driver is ready to offer them a 100 taka note. And in the streets of Dhaka a driver can afford to be as unruly and indisciplined as he wishes to be. It doesn't matter if he is absolutely ignorant of the traffic rules and goes on continuously violating them; neither does he have to have a valid licence; he can defy the red light and pick up more speed than allowed. Because he knows he can get away with anything. Traffic sergeants are sometimes a worry, but not big enough if the driver is ready to offer them a 100 taka note.

Traffic sergeant Sohel Arman, predictably objects to such sweeping allegations of taking bribes against all traffic sergeants. "As in any other profession, there are also bad people among us," he argues.

Traffic sergeants, who are entrusted with the task of ensuring order in the streets and disciplining the law-breaking drivers, are often viewed as the real culprits by many commuters.

"They allow unfit vehicles to operate and fake licence holders go on driving, because if everything is in order they won't be able to take bribes," quips Jamil, a BBA student and a regular bus passenger.

Sohel denies the charge. "Everyday we are lodging hundreds of cases against the faulty drivers. Besides, we also have to go by some rules. If someone drives with a fake licence, I can charge him a penalty of Tk 200. And that's the only thing we are authorised to do," he explains their limitations. After paying the penalty the driver is purged of all sins and he goes on driving until another unfortunate moment comes when he is once again signaled to stop another day by another sergeant at another place.

Sometimes the passengers on board also encourage the drivers to go fast, alleges another minibus driver Sharif Mia.

"They keep on nagging that 'buses from behind are going ahead of you, what the hell you are doing'" Alamgir, a minibus driver on Motijheel-Mirpur route, complains.

"Very often, passengers insist on going fast and even encourage drivers to defy signals because they are in a hurry," echoes baby-taxi driver Alam.

But not all passengers are like that. Often enough it is the drivers that are in a hurry and it is they who lead the passengers to their perils.

There are examples of drivers whose recklessness has led to many deaths, even their own. When Shahedul Karim and his family moved to Dhaka, they were on the look out for a chauffeur. Upon hearing of such an opportunity, a man approached the family to try out for the job. Being the meticulous sort of person that he was, Shahedul took the man out on a test drive, to verify his claims of being an experienced hand at the wheel. The so-called 'experienced-hand' had barely gone out of the residential area that the Karims were living in, when he sped up, dodged a tree and almost crashed the car at a nearby bus stop. The man was obviously not given the job.

Making Roads Safe

With around 160 deaths per 10,000 motor vehicles a year, Bangladesh has one of the highest fatality rates in road accidents in the world. To make matters worse, new motorised-vehicles are being poured into the streets of the capital at a rate of 8 percent every year.

Most of the road accident victims in the capital are pedestrians. "They contribute about 63 percent of road accident fatalities and one third of the injuries," says Dr Mazharul Haque, director of BUET's Accident Research Centre (ARC). In a recent research, Dr Haque showed that fatal accidents related to pedestrian-motorised vehicle collision has increased markedly by 29 percent over the last 10 years.

Mohiuzzaman Quazi, senior transport engineer of the World Bank, supports Dr Haque's findings. Quazi blames it on the haphazard urbanisation that the city has been going through. Because of unemployment and sheer poverty in rural areas, people come to the city every day in the thousands. Most of them, Quazi believes, have never been exposed to the fast-moving city landscape. "People moving into the city -- most of whom end up being rickshaw-pullers -- are often culturally different from people born and raised in urban conditions," he continues.

Quazi points the finger at a number of factors for the city's rapidly deteriorating traffic. "Dhaka lacks proper pedestrian crossing facilities and it is a nightmare for anyone who dares to walk on foot; most of the rickshawallahs and CNG drivers are not properly trained," he says.

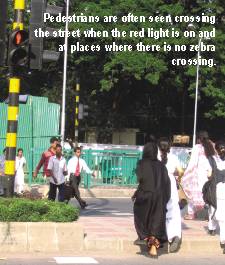

Dr Tanweer Hassan, an associate professor of Department of Civil Engineering in BUET, explains what he calls 'the human factor' in the development of an efficient traffic control. "Mostly because the walkways are occupied by hawkers, pedestrians cannot use the footpaths. They also tend to take a path that is the shortest distance between two points, crossing at midblocks or failing to stay in crosswalks," Dr Hassan says.

"As pedestrian regulations are not properly enforced, many passers-by consider themselves outside the law in traffic matters," he continues, "most of them do not use underpass or footbridges."

On top of it all, says Dr Md Shamshul Hoque, research specialist of the ARC, more than half of the trucks and buses plying the city roads are faulty. "A recent survey on heavy vehicles has revealed that only 42 percent of trucks and buses have defect-free lighting system." For the supply of both passenger and transport vehicles the country primarily depends on import. "Because of this and on the plea of the dearth of spares, there is a tendency to ply defective vehicles on the roads," Dr Hoque continues.

Dr Hoque also says that buses built in the country are often constructed on truck chassis that "offer little or no protection to passengers in the event of an accident."

"Leg room between seats is often exceptionally poor in order to squeeze the maximum number of seats in the vehicles. Seat frames themselves are usually formed from angle steel, frequently causing amputation of limbs in an accident," he says.

The government has to come forward to clean up this mess. "To encourage owners to keep their vehicles fit and roadworthy, duty and sales tax on items of brake system and safety glasses should be totally withdrawn," Dr Hoque says. The professor believes in order to promote overall motor vehicle safety, maintenance should be given more emphasis than that of imposing restriction on importing used vehicles. Drivers applying for a licence should go through a rigorous training. The government has to make the pedestrians aware of traffic laws before it starts enforcing them. Making the roads safe for everyone is not impossible, as Dr Haque says, "Accidents and injuries are not acts of God."

-- Ahmede Hussain

|

However, he did get another job as a black cab driver. Within a few months of getting the job, speeding his way to Ashulia, he swerved his car to avoid hitting a group of people crossing the road and killed the four passengers in his taxi. He died eventually, after being taken to the closest hospital.

On April 20, the popular band Black was on its way home to Dhaka from a concert in Chittagong, when at around 3:30 am in the morning, the microbus lost control and sped off its tracks. The vehicle cart-wheeled a number of times, throwing its passengers out on the road. Well-known sound engineer Mobin, who was accompanying the band, died almost immediately. Two of the members of the band and the driver of the vehicle were critically injured and were rushed to a nearby hospital. Even though most of the members have recovered, Miraj, the bassist of the band is still recovering in Singapore, still waiting to get a bone drafting done on his left knee so that he can walk once again.

This accident caused a lot of outcry amongst the admirers and fans of this band, where many companies like Grameen Phone rushed to their assistance. However, what people fail to realise is that these kinds of accidents occur everyday in our country, killing hundreds. The people in this country have taken the streets and the vehicles they drive in for granted and hardly care for their own safety, or for the passengers they carry. Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |

| |