|

Icons

of History

Mustafa

Zaman

Memorials

are signs in the shape of architectural structures or

sculptures. They rekindle our spirit that we once invested

in actions, actions that made history and later translated

into deferential forms or structures.

In Bangladesh the Shahid Minar that was erected to commemorate

the martyrs of Language Movement set off the culture

of building monuments. Later, after the seminal victory

in 1971, structures dedicated to the history of independence

were built. Though years have elapsed since the completion

of these national monuments they aptly define our cultural

and historical heritage.

But there is another hidden element behind these glorious

structures. There are many untold stories of the artists

who turned their visions into such tangible forms. The

architects behind the main monuments that depict our

struggle for freedom give a rare insight into the thoughts

behind their creation, their moments of frustration

and elation during envisioning or planning these remarkable

labours of love.

Savar

Smritishowdha Savar

Smritishowdha

Syed

Mainul Hossain, the architect of the National Monument,

used to work as consultant in a firm in 1978 when an

open competition for the design for the national monument

at Savar was announced. “There were two competitions

all together. The juries were not satisfied with the

submissions first time around. So, there was a second

competition and it was on this occasion that my design

was given the first prize,” remembers Hossain.

Hossain

was not satisfied with his first attempt. “I had this

idea of two columns being compressed to meet at the

top to evoke a feeling of upward thrust,” says Hossain.

It

was the second time that his effort found proper expression.

He was a man engrossed in the daily grind of his office

duties. Yet he found time to build his dream project

in a small-scale. “I built a 64/1 model, and used to

keep looking at it while lying in bed to get the feel

of the real structure seen from its base,” recalls Hossain.

He later built a larger prefabricated model that he

submitted for the competition.

His

friend, Badrul Haider, a working architect, remembers

how Mainul Hossain came to his place with all the separated

components of his model in his hands on the submission

day. “When he assembled them on a table I was sure that

this was the winning entry, ours were nowhere near his,”

recalls Badrul.

Seven

pointed L-shaped concrete structures with variable heights

and widths are sequentially placed to look like a huge

153 feet high pointed triangle that seems splayed out

at the base from the front. Built in the middle of a

spread of an 84-acre area, designed by the architect

and a freedom fighter Abdur Rashid, it includes everything

from the original mass grave and the early bhittiprastar

(foundation stone) to helipads, a parking lot, a stretch

of wall for mural and areas of gardens. It is lined

with a buffer zone to separate the marked zone from

the rest of Savar.

From

its entrance to the monument, one has to walk a straight

passage divided into four plazas. The plan for the area

was finalised right after independence, though it was

during the early years of the autocratic regime of Ershad

that the project was hurriedly completed compromising

durability and the original plan.

The

main structure that Hossain designed in 1978 won the

first prize. It was completed within three months. By

the end of 1982 the structure stood tall, though cracks

were visible in many of the structures.

Hossain

remembers how he felt climbing up the 150 ft high bamboo

scaffolding, “It was an experience to see the Savar

in its entirety from that height, I was lured to go

up and scan the horizon,” Hossain says recalling his

days as a consultant who periodically visited the sight.

The architect, who was later decorated

with Ekushey Padak and IAB honour, had to witness his

design being materialised so hastily that it was born

with faults. “The cracks that run through the structures

are the result of lack of experience on the part of

the builder and the span of time it was given,” contends

Hossain who was for cutting down of costs by sticking

to the idea of building thinner structures.

Seven harmonious structures correspond

to 52, the year of the Language Movement, the dates

of freedom and independence days, respectively 16 and

26. “When the two digits are added of each of the figure,

you get the number 7. This spurred me to go for seven

structures,” reveals Hossain, an architect who has given

this nation one of its original structures.

Aparajeyo

Bangla Aparajeyo

Bangla

“There are monuments recognised and

built by the government, and there are monuments that

are build by the people, mine is of the second kind,”

argues Syed Abdullah Khalid, the sculptor who built

the first national monument. The idea of sculpture as

a monument was not new in Bangladesh. Hamidur Rahman

and Novera Ahmed set the precedent by building a structured

sculpture in memory of the martyrs of the Language Movement.

Aparajeyo Bangla is the reflection of

the student movements that helped shape a political

culture of dissent that culminated into movements and

lastly resulted in the freedom struggle. “This sculpture

is a reflection of our collective consciousness and

political milieu that it gave birth to, the general

students had a strong bearing on that,” says the artist

who was a young teacher at the Department of Fine Arts

at the Chittagong University in 1973 when the project

was launched.

The Dhaka University Students' Union,

DCSU and the authority joined hands to give the spirit

of liberation a physical and symbolic shape.

“The model for the work was built within

three months starting from January of 1973,” Khalid

remembers. The then Vice Chancellor of the university

came to see and “was taken by its expressive quality”.

When he came to know that it would cost Taka 50 thousand

to build, he gave the go ahead. Though later DUCSU had

to play a role in providing the fund. The sculpture

now stands at 17 and half feet in concrete structure,

including the height of the base.

Work started amidst opposition from

the so-called pro-Islamic fronts. “Making of the sculpture

was another movement all together, I had to campaign

for it. DCSU and the pro-liberation forces had to fight

for it,” remembers Khalid. Yet on the day of the murder

of Bangabandhu on 15 August 1975, work came to a halt.

Khalid recalls how resuming its construction

was another war. Disappointed and demoralised, the artist

left for England where he was to receive a diploma in

metal casting. This was in 1977, at the end of this

year he was informed that the work of the sculpture

would restart.

In

December, he was in Dhaka to give impetus to the signature

campaign of the general students. By then Anwar Jahan's

sculpture, which was awaiting the work of curing after

casting was done, was uprooted one night. “

That same pro-Islamic element made attempts to break

the unfinished Aparajeyo Bangla,” recalls the artist

who thinks that the monuments are expressions of a collective

mind. “They are the structures where mind and matter

come together,” he adds.

At the end of December, 1978, the work

resumed. It took another whole year to finish. It was

inaugurated in a DUCSU-organised ceremony on 16 December

1979 by 12 freedom fighters who came in wheel chairs

to unveil a structure that now upholds both the history

of independence and its making.

The

Rayerbazar Badhabhumi Smritishoudha The

Rayerbazar Badhabhumi Smritishoudha

Built by two friends Farid Uddin Ahmed

and Md. Jami Al Shafi, the Rayerbazar Memorial is a

belated homage to the intellectual martyrs. It was completed

in 1999 and was opened on 14 December on that year.

Alongside the sporadic killing that took place, at the

last moment of the war, when there was only two days

left to the surrender of the Pakistan force, the collaborators,

the deshi quislings gave the wholesale killing by the

army a final and freaky touch. They implemented their

master plan to wipe out the intellectuals who had the

courage to stand against them while not leaving the

country.

The two young architects were faced

with the problem of bringing into view the solemnity

befitting the martyred intellectuals. It was in 1993

that the competition was held, and the two fresh graduates

from the Department of Architecture, BUET bagged the

first prize.

“Couple of days before the submission,

when our main model was complete, and we were giving

it the additional touches, two little kids of our landlord

came in and spontaneously uttered, 'Bhaiya this model

does not look good, it makes you sad',” remembers Shafi.

For he and his partner the response of these children

was a reassurance of the mournful feeling the small-scale

structure emanated.

Shafi

also remembers how frustrating it was to see their project

being put off for years. Out of 22 participants, their

model was declared first by the jury, yet it was not

until 1996 that the foundation stone was put up. “We

were not sure then that this project would be implemented,

as we had seen many other ventures stalled to the point

of not being built,” says Shafi recalling how unsure

he felt back than.

At

present, the project that altered their standing among

the peers are in utter neglect. Maintained by the Public

Works Department (PWD), it bears no sign of being looked

after. The granite pillar, one of its main components,

is already losing its stones. As a monument, its unique

feature lies in the uneven construction of a curved

wall with a big squire punch on it that replaces the

traditional idea of a symmetrical obelisk. At

present, the project that altered their standing among

the peers are in utter neglect. Maintained by the Public

Works Department (PWD), it bears no sign of being looked

after. The granite pillar, one of its main components,

is already losing its stones. As a monument, its unique

feature lies in the uneven construction of a curved

wall with a big squire punch on it that replaces the

traditional idea of a symmetrical obelisk.

“During its construction relatives of

the martyrs used to visit the site, some used to recite

the Koran, some came to pass time in silence,” recalls

Shafi. Ahmed says that they all loved what they saw.

“It is a strong existence, and it is out of reach,”

says Ahmed. Flanked by a body of water, the curved break

wall gives the feeling of incompleteness. “Both soft

and hard materials converge to make the smritishowdha

complete,” Shafi reflects. A water body, especially

made bricks, grass, the plaza or the podium in layman

terms, and carefully planted trees, of which the most

significant of them is the banyan tree included at one

side of the foreground, are the elements that come together

here at Rayerbazar. The banyan stands as a reminder

of the old banyan that was the last post of Dhaka, past

that the low lands began. The original one still stands

many yards away. Though unattended, it is the tree up

to which the martyrs were brought in blindfolded by

car and then from that point on were led to the low

land to face their terrible fate.

The

Shadhinata Stambha

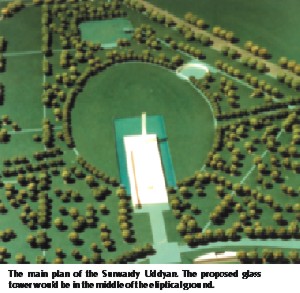

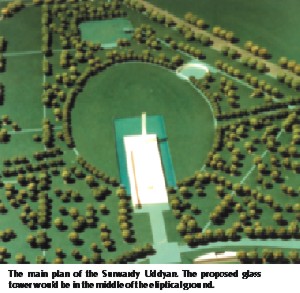

One of the recent cases of dithering

with a project that has to do with the history of independence

is the installation at the Suhrwardy Uddyan. It was

a huge project that was taken up by the Awami league

government back in 1997. It had its share of the usual

flak from the opposition, as they saw it as a partisan

venture.

The

Urbana, run by young architects like Kashef Mahboob

Chowdhury and Marina Tabassum, with other colleagues

working with them at the time, were the ones who envisaged

a glass tower that won over the then head of the government.

The tall glass tower proposed by the firm Urbana was

hinged around an equally large expenditure. Sixty-seven

crore Taks was the proposed amount for the glass tower

alone, and the another hefty 82 crore was estimated

for the underground museum and the plaza upon which

the main tower would stand. “There is no national archive

or museum to preserve the history of independence. We

elaborately planned this underground museum to fill

out that gap,” reflects Kashef who thinks the National

Museum does not have adequate space or exhibits dedicated

to the war of independence. The

Urbana, run by young architects like Kashef Mahboob

Chowdhury and Marina Tabassum, with other colleagues

working with them at the time, were the ones who envisaged

a glass tower that won over the then head of the government.

The tall glass tower proposed by the firm Urbana was

hinged around an equally large expenditure. Sixty-seven

crore Taks was the proposed amount for the glass tower

alone, and the another hefty 82 crore was estimated

for the underground museum and the plaza upon which

the main tower would stand. “There is no national archive

or museum to preserve the history of independence. We

elaborately planned this underground museum to fill

out that gap,” reflects Kashef who thinks the National

Museum does not have adequate space or exhibits dedicated

to the war of independence.

The

design of the plaza is a rectangle upon which the Shikha

Chirantan, the 7 feet high triangular installation in

commemoration of the 7 March address of Banga-bandhu,

a long, continuous wall along the left side, a shallow

round pool at the middle with a hole that slowly sucks

away the water and lastly at the end the huge glass

tower is placed.

The

controversy that surrounds the monument in best part

was concerned with the felling of trees. Although as

a city park, the Uddyan was never designed according

to standard norms. It was a huge open field in the 60s,

and later in the eighties became home to unplanned vegetation

and sporadic clustered areas of trees.

Kashef

and his colleagues proposed a gradual transformation

of this park, which is one of last few outposts of greenery

in this city. They also had a plan to produce in the

middle of the park an elliptical clearing. On the fringe

of the clearing a sunken amphitheatre designed.

Out

of forty-four firms participating Kashef and Marina's

was the winning design. At present, rumours abound regarding

its fate. Some are buying that the present government

is planning to include sculpture of the late president

Zia. “This is all hearsay. It is our design and we did

not try to put our signature in it, we fashioned it

in way a national monument ought to be,” contends Kashef.

The

project now is left to deteriorate in its incomplete

state. Work came to a halt on the night of the last

parliament election. “We planned a living tower. The

look of it changes during the day and at night it is

lit from within it and is the major source of light

in this huge area. Any change to that idea would undermine

the significance of the project,” believes Kashef.

The

Mujib Nagar Sritishowdha

The

plan for Mujib Nagar Smritishowdha at Mherpur was formulated

right after independence. But the real work began as

late as the early eighties. It was in 1984 that the

designs were called from architects and artists. Diagram

Architects, run by three young architects-- Saiful Haque,

Jalal Ahmed and Khaled Noman, won the first prize for

their unusual design structured in grid pattern. The

plan for Mujib Nagar Smritishowdha at Mherpur was formulated

right after independence. But the real work began as

late as the early eighties. It was in 1984 that the

designs were called from architects and artists. Diagram

Architects, run by three young architects-- Saiful Haque,

Jalal Ahmed and Khaled Noman, won the first prize for

their unusual design structured in grid pattern.

Though

the sprawled-out design of the three architects made

an impression in the minds of the juries, which resulted

in their winning of the first prize, the then autocrat

H.M. Ershad arbitrarily ordered government architects

to come up with a design that was later built.

The

multiple sun-dials that now exist is the one built by

the Department of Archtecture, Ministry of Work. The

architects were Shah Alam, Md. Tanweer, Tanweer Karim

and A.S.M. Ismail.

“Winning

a competition then gave us a moral boost, but it was

frustrating to see that a prize-winning structure was

side-stepped to make way for another design” says Haque,

who now runs his own firm at Dhanmondi.

The

concept of the original design sprang from a photograph,

where Nazrul Islam, the then acting President of the

newly declared country, and other prominent leaders

and the attending crowd that included the villagers

that came from near and far. “We kept the scale human,

as our idea was to express the sense of fraternity that

was the essence of 17 April, 1997, when the interim

government was formed at Mujib Nagar,” Haque informs.

The original design was an installation that took into

account the existing environ. Its build was an expression

that puts the idea of vertical monuments on its head.

Photo

by Zahedul I Khan, Syed Zakir Hossain

and Diagram Architects |

Savar

Smritishowdha

Savar

Smritishowdha Aparajeyo

Bangla

Aparajeyo

Bangla  The

Rayerbazar Badhabhumi Smritishoudha

The

Rayerbazar Badhabhumi Smritishoudha At

present, the project that altered their standing among

the peers are in utter neglect. Maintained by the Public

Works Department (PWD), it bears no sign of being looked

after. The granite pillar, one of its main components,

is already losing its stones. As a monument, its unique

feature lies in the uneven construction of a curved

wall with a big squire punch on it that replaces the

traditional idea of a symmetrical obelisk.

At

present, the project that altered their standing among

the peers are in utter neglect. Maintained by the Public

Works Department (PWD), it bears no sign of being looked

after. The granite pillar, one of its main components,

is already losing its stones. As a monument, its unique

feature lies in the uneven construction of a curved

wall with a big squire punch on it that replaces the

traditional idea of a symmetrical obelisk. The

Urbana, run by young architects like Kashef Mahboob

Chowdhury and Marina Tabassum, with other colleagues

working with them at the time, were the ones who envisaged

a glass tower that won over the then head of the government.

The tall glass tower proposed by the firm Urbana was

hinged around an equally large expenditure. Sixty-seven

crore Taks was the proposed amount for the glass tower

alone, and the another hefty 82 crore was estimated

for the underground museum and the plaza upon which

the main tower would stand. “There is no national archive

or museum to preserve the history of independence. We

elaborately planned this underground museum to fill

out that gap,” reflects Kashef who thinks the National

Museum does not have adequate space or exhibits dedicated

to the war of independence.

The

Urbana, run by young architects like Kashef Mahboob

Chowdhury and Marina Tabassum, with other colleagues

working with them at the time, were the ones who envisaged

a glass tower that won over the then head of the government.

The tall glass tower proposed by the firm Urbana was

hinged around an equally large expenditure. Sixty-seven

crore Taks was the proposed amount for the glass tower

alone, and the another hefty 82 crore was estimated

for the underground museum and the plaza upon which

the main tower would stand. “There is no national archive

or museum to preserve the history of independence. We

elaborately planned this underground museum to fill

out that gap,” reflects Kashef who thinks the National

Museum does not have adequate space or exhibits dedicated

to the war of independence. The

plan for Mujib Nagar Smritishowdha at Mherpur was formulated

right after independence. But the real work began as

late as the early eighties. It was in 1984 that the

designs were called from architects and artists. Diagram

Architects, run by three young architects-- Saiful Haque,

Jalal Ahmed and Khaled Noman, won the first prize for

their unusual design structured in grid pattern.

The

plan for Mujib Nagar Smritishowdha at Mherpur was formulated

right after independence. But the real work began as

late as the early eighties. It was in 1984 that the

designs were called from architects and artists. Diagram

Architects, run by three young architects-- Saiful Haque,

Jalal Ahmed and Khaled Noman, won the first prize for

their unusual design structured in grid pattern.