| Cover Story

Ending the Legacy of Murder

Former prime minister Sheikh Hasina was the target of the August 2 grenade attacks on an Awami League rally in 2004. |

Our political history is riddled with tales of conspiracy and murder. Most unfortunate, however, is the precedent that has been set over the decades, of killers getting away with impunity.

Kajalie Shehreen Islam

Four years ago on August 21, 23 people were killed in a series of grenade attacks at an Awami League (AL) meeting being held in front of the party office at Bangabandhu Avenue. Though the prime target, former prime minister and the then leader of the opposition Sheikh Hasina, survived with ear injuries, a number of central AL leaders, including Women's Affairs Secretary Ivy Rahman, were killed, over 200 people injured. Injuries ranged from splinter wounds, loss of eyesight and limbs. Some of the victims still carry the splinters, which could not be removed, inside their bodies.

Less than six months later, on January 27, 2005, former finance minister Shah AMS Kibria and four other AL activists were killed in another grenade attack on an AL rally in Habiganj; about 70 others were injured. Despite allegations of a controversial investigation, the trial began in May 2006 but was halted due to a High Court (HC) stay order. The case is now pending at the Sylhet Divisional Speedy Trial Tribunal.

Of the 10 accused in the Kibria case, eight are in detention and two absconding. All 10 are Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) men, one of them is the district BNP vice-president AKM Abdul Quayum, who was later expelled from the party. Links have also been made to the Harkat-ul Jihad al-Islami (Huji), but Kibria's family and party members claim that the masterminds behind the killing have been left out of the investigation and have urged the caretaker government to fairly investigate the murder.

As for the August 21 attacks, case proceedings finally began last month after police filed a chargesheet against 22 people, including former deputy minister for education in the BNP-led alliance Abdus Salam Pintu and eight absconding Huji members. This came out after an intense and long drawn out drama surrounding the investigation. The initial probe was carried out under the direct supervision of Lutfozzaman Babar, state minister for home affairs at the time. The 20 persons arrested following the investigation, which included a student and an AL leader and ward commissioner, however, were not found guilty in the later investigation. Another twist was brought about with the confessions of Joj Miah and two others who claimed that a criminal gang had carried out the attacks. These confessions were later found by the present administration to have been obtained by force, and by paying Joj Miah's family a few thousand taka monthly. At one point, even a "foreign enemy" was implicated in the incident. Even after the usual blame game and all the twists and turns in the investigation process, doubts still remain as to whether the real culprits behind such a well-planned and deadly attack have been identified.

***

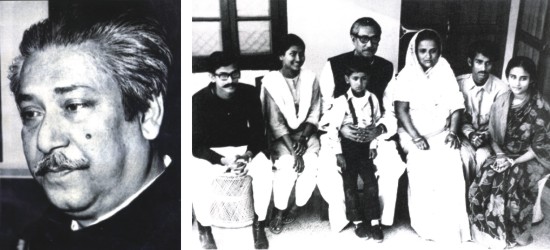

In a nation that has witnessed the killing of its national leaders, including its founding father, almost from its birth, these killings do not come as a shock. The trend of killers getting away with impunity has been set early in our history. The same killers who on August 15, 1975 murdered Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and 21 members of his family and household, including children and pregnant women, also assassinated four national leaders -- Syed Nazrul Islam, acting president of the government-in-exile, prime minister Tajuddin Ahmed, finance minister M Mansur Ali and minister for home affairs, relief and rehabilitation AHM Qamruzzaman -- inside a prison cell, on November 3, 1975. The latter massacre was a part of a contingency plan in the event that a counter-coup occurred, basically, to wipe out a whole leadership whom the killers did not see fit to govern the nation. Not only were the perpetrators not punished for their crimes, but they were actually allowed to escape and even rewarded by the State with promotions and diplomatic postings abroad.

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who was assassinated along with most of his family on August 15, 1975.

On May 30, 1981, President Ziaur Rahman, who ultimately came to power after the coups and counter-coups of the 1970s, was assassinated by a faction of army officers, in approximately the 20th coup attempt against Zia himself. The killing of Brigadier Khalid Musharraf, Colonels Huda and Haider in November 1975, as well as the execution of Col. Abu Taher by Zia and the hasty trial and punishment of Zia's own killers, were also said to be politically motivated.

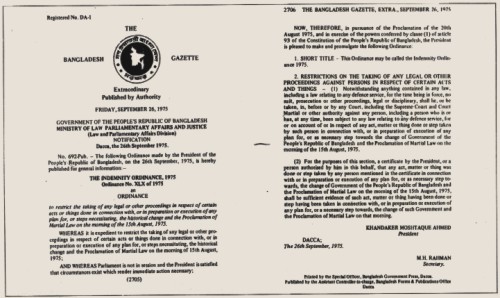

But the culprits of the Bangabandhu and jail killings were, for 21 years, covered by the Indemnity Ordinance passed by the government under president Khandaker Moshtaque Ahmed, which was later legalised in parliament. Only in 1996 after the AL came to power was the ordinance repealed and a murder case filed on October 2 of that year. In November 1998, 15 former army officers were awarded the death penalty by the trial court in the Bangabandhu murder case. The HC later upheld the death sentences of 12 -- Syed Farook Rahman, Bazlul Huda, Shahriar Rashid Khan, Muhiuddin, AKM Mahiuddin, Khondaker Abdur Rashid, Shariful Haque Dalim, AM Rashed Chowdhury, SHMB Noor Chowdhury, Abdul Majed and Muslemuddin. The first five are currently in custody. The latter six are absconding (Muslemuddin is rumoured to be dead), while Aziz Pasha, who was also on the run, died in Zimbabwe.

On October 20, 2004, Muslemuddin, Marfat Ali Shah and Abdul Hashem Mridha (all absconding) against whom charges “were proven beyond doubt” in the jail killing case, were sentenced to death. Syed Farook Rahman, Bazlul Huda, Shahriar Rashid Khan, AKM Mahiuddin, Khandoker Abdur Rashid, Shariful Haque Dalim, SHMB Noor Chowdhury, Abdul Majed, AM Rashed Chowdhury, Ahmed Sharful Hossain, Kismat Hashem and Nazmul Hossain were sentenced to life for abetting the murderers. Five people were acquitted in the jail killing case, the verdict of which the slain leaders' families and the AL rejected as being "farcical" and for which even the judge blamed the investigation officer for faulty investigation.

Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmed, M Mansur Ali and AHM Qamruzzaman -- the four national leaders killed in a prison cell on November 3, 1975.

The Bangabandhu murder case is currently awaiting hearing in the Appellate Division. According to the State Counsel for the case, there are not enough judges in the Appellate Division to hear it. Out of the five judges, three cannot hear the case -- two were embarrassed and one passed a verdict on this case in the HC. A minimum of two judges is required for hearing cases in the Appellate Division.

In the jail killing case, the defence lawyers and State defence lawyers had already argued their cases while the State Counsel completed its arguments last Thursday.

****

The perpetrators of the Bangabandhu and jail killings were self-proclaimed. In an interview with the Sunday Times on May 30, 1976, Syed Farook Rahman, said to be the mastermind behind the killings, said, “Let the Bangladesh government put me on trial for the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. I say it was an act of national liberation. Let them publicly call it a crime.” He even cited five reasons for which he “ordered” Mujib's killing.

But the chain of reactions which Farook and his accomplices set in motion did not end there. The struggle for power, the coups and counter-coups and killings continued, so much so that veteran journalist Anthony Mascarenhas, who followed the liberation struggle of Bangladesh and the chaotic years which followed, has termed it Bangladesh's "legacy of blood", beginning from the partially flawed leadership of Sheikh Mujib which set off the killings in the first place. When the killers were finally forced to face up to their crimes, however, albeit 21 years later, the bravado faded despite all the evidence to the contrary, they denied responsibility.

Ahsanullah Master, Ivy Rahman and Shah AMS Kibria killed in 2004 and 2005.

Clear crimes, identified killers -- why then did it take so long for the process of justice to be started? The most obvious reason is that those in power after the crimes did not care to have justice delivered.

"In most of the political killings in our history," says Advocate Shahdeen Malik of the Supreme Court (SC), "a part of the State was involved. Thus it was difficult for the other parts of the State to take on these issues even if they wanted to. It would be difficult to turn around and strike at their own roots, saying that the killings from which they had benefited were illegal. It would have made the legitimacy of those who came to power after the killings very questionable. "

"Ideally," continues Malik, "the trials would have taken place immediately after the crimes. But those who were in power right after were the beneficiaries of these crimes -- if you are the beneficiary of a crime you won't be the most enthusiastic prosecutor of that crime." He points out that President Ziaur Rahman's killers were tried and punished not because it was an issue of right and wrong, but because someone derived the benefits, whereas in the former two cases, it was beneficial not to prosecute the culprits.

"The case and killing of Bangabandhu and his family was for all intent and purpose a

Advocate Anisul Huq |

murder case," says former prosecutor and current State Counsel for both the Bangabandhu and jail killing cases, Anisul Huq. "But unfortunately, none of the governments that succeeded until 1996 lodged a case. Those who were in power between 1975 and 1990, 1991 and 1996, and 2001 and 2006 were the beneficiaries of the murder of Bangabandhu. They didn't want to bring to justice and punish the killers of Bangabandhu and his family, because if it happened then maybe many unknown truths would have been revealed. This actually means that they have endorsed the killings and by so doing thwarted justice. This position was corrected in 1996." "We crossed a lot of hurdles and finally arrived at a verdict," continues Huq. "Again, those who were the beneficiaries of this murder created obstacles by denying our consistent request that the Appellate Division hear this case, that an ad hoc judge be appointed, which is permitted by the Constitution. Our principal reason for such a demand was that these two cases needed to be finished for establishing the rule of law."

"What we have seen after the murder of Bangabandhu and his family," Huq goes on, "is a sequence of political murders which culminated finally in the killing of Ziaur Rahman. Had this trial been held earlier, then at least the message would have been conveyed that the perpetrators of such killings are brought to justice, which would put an end to such political killings. It would have conveyed a message to the populace that nobody is above the law, everybody is equal in the eye of law, which is the sine qua non for establishing the rule of law."

****

What does it say for the legal and justice system of a nation and what example does it set for its people, when murder after murder goes without investigation, trial and the meting out of justice?

As far as the people's faith in the judicial system is concerned, Advocate Shahdeen Malik does not think the consequences of the above cases play a very important role.

"People have still not accepted our formal justice system," he says. "If you catch a mugger, beating him up is most people's idea of justice." Not more than 30 percent of normal murder cases get formal justice, according to Malik. In the other 70 percent, settlements are made through compromise. The conviction rate in criminal cases is less than 10 percent. "There is a big disjunction between formal justice and people's notion of justice. In the prevailing notion, the latter is the better justice where it is ensured 80 percent."

Extra-judicial killings extract a high price from society, however, believes Malik. "Fast forward to crossfire, where a significant part of the State machinery is involved. The same story has been repeated 600 or 700 times, that the criminal was shot while escaping. These are clear instances of extra-judicial killings. What worries me most," says Malik, "is that once extra-judicial killings become an accepted way of dealing with a problem in a society, however small a number, things can get out of hand. Most societies in the last 50 years which have tolerated this as a quick solution have ended up suffering tens of thousands of killings. It's just a matter of time. Now the number may be 500 or 700, but for many societies the figures very quickly escalated into the thousands. The transition was very quick."

"The basic rule of thumb," says Malik, "is that you don't keep those who have fought a war in the army. The US demobilised those who fought in Iraq within two years. A person with a gun is a dangerous person, one who has used a gun randomly, whether in war or elsewhere, is dangerous. With a person who becomes used to killing, however justified, however legal, there is always the fear of their using the gun again illegally. We didn't understand this in 1972 and those who fought in 1971 continued to battle amongst themselves."

***

Decades after the crimes, the process of justice has begun, but obstacles still remain. Firstly, there is the question of investigations and their validity after such a long time has passed. How foolproof are probes carried out decades after an incident?

"With regard to the jail killings, a case was filed on November 4, 1975, but it was stopped by the successive governments," says Advocate Anisul Huq. "This is unheard of. What these successive governments have proved or left for posterity is that this was actually a crime sponsored by the successive governments. They have taken the onus of being a party to it. By their conduct in the jail killing case they have only substantiated the fact of being beneficiaries of both the killings."

President Ziaur Rahman, killed in around the 20th coup attempt on his life on May 30, 1981. |

As for the Bangabandhu murder case, Huq says there were problems due to the delayed investigation. "It was difficult and I'm not saying it was foolproof, no investigation is foolproof. What I am saying is that as much as was possible after 21 years was done."

Not only is delayed justice a problem, but also the state of the judicial system itself, says Huq. "There are seven to eight judges of the HC division embarrassed to hear this case. That speaks of the pitiful state of our judicial system. If we are looking for accountability, if we are working for transparency, then I think these issues of the embarrassment of judicial officers and judges should also be resolved."

Despite all the hurdles, however, the State Counsel is confident about its case. "I'm quite confident that we have been able to prove the charges of murder of the accused persons in these cases. We faced difficulties in certain areas and those difficulties were actually created by the party in power at that time. But from the time 2001 to 2006, the BNP made positive contributions towards the end of thwarting justice." Huq believes that the cases will be resolved "soon enough, without setting a date".

The long drawn out process, however, is not the only problem. Even after the cases are resolved, the matter of finding and punishing the culprits remains. Almost half the culprits in the cases are currently absconding. With many, there is the issue of extraditing them from the countries in which they now reside, including the US, Canada, Libya and Pakistan.

M. Aminul Islam, high commissioner of Bangladesh to Canada between 1998 and 2000, explains the problem of extraditing Nazmul Hossain and Kismat Hashem from Canada after they were convicted and sentenced to death in the Bangabandhu murder case in 1998. Nazmul Hossain was posted at the Bangladesh High Commission in Canada and later married a Canadian woman and became a citizen of that country. Kismat Hashem also settled in Canada, started a business there and became a Canadian citizen.

"After the judgement in the Bangabandhu murder case," says Islam, "they could not be sent back as Bangladesh did not have an extradition treaty with Canada. Thus efforts were made to conclude an extradition treaty and drafts of treaties which Canada had with other countries were sent to Bangladesh for examination."

A major problem, however, was the sentence itself, says Islam. "After the judgement, the Canadians pointed out that the men had been sentenced to death. There is no capital punishment in Canada and neither Canadian nationals nor citizens of any other country would be extradited from Canada to countries where they would face the death penalty. Thus it was felt that even if an extradition treaty were to be concluded, the two accused would not be extradited until and unless the Bangladesh government gave a guarantee that the death sentence would be commuted to jail terms." As Nazmul Hossain and Kismat Hashem have been acquitted in the Bangabandhu murder case and now only face life terms in the jail killing case, that problem is gone, says Islam, but the extradition treaty is yet to be completed. The former ambassador also points out that when many years ago a Canadian citizen of Bangladeshi origin had fled from Canada to Bangladesh, Canada was very interested in signing an extradition treaty with Bangladesh but the latter country was not so keen at the time.

*****

|

| The Indemnity Ordinance passed in 1975, giving Sheikh Mujib's killers (Below) immunity from prosecution. |

|

According to Advocate Shahdeen Malik, most political killings in our country have not been addressed and it is unlikely that they will be. "The Bangabandhu and jail killing cases will probably be completed," he says, "and something might be done in the August 21 case, the really high-profile ones. But at the next level, such as the killing of local leaders like AL's Manzurul Imam, for example, it is unlikely that much will be done. Even the Kibria murder has not made much headway."

Indeed, there have been scores of political murders over the decades. Some have wiped out a whole leadership. Others have stifled opposition and thwarted differences. From the killing of Salim and Delwar, Raufun Basunia and Nur Hossain, among others, during the Ershad era, to the bomb blast at a Communist Party of Bangladesh (CPB) meeting in 2001 which killed seven people and injured over a hundred; from the killing of Jaityo Samajtantrik Dal (JSD) leader and freedom fighter Kazi Aref in 1999 to the violent deaths of AL leaders Mumtazuddin Ahmed and Manzurul Imam in 2003 and AL lawmaker Ahsanullah Master in 2004 -- the cases are endless, but justice has been served in few.

Throughout our history, violence has been seen as the way to eliminate opposition and rise to power. Because of the number of unsolved or unresolved cases, the unfortunate example of doing so with impunity has also been set. The politicisation of these crimes against not political but national leaders, has created further obstacles in the path of justice. With the most high-profile cases taking decades to be resolved, little hope can be held for those in lesser positions of power. Yet the fact that they are at long last being addressed is a step. If dealt with fairly and swiftly, it could work towards mitigating the unfortunate precedents set in our history, which promised the perpetrators of such brutal crimes immunity and impunity.

A Nation's Shame

In spite of a Section 144 declared in Dhaka, five lakh people from 72 different political and cultural organisations gathered together in front of the Shaheed Minar on 26 March 1992. With Jahanara Imam at the helm, Ekatturer Ghatak-Dalal Nirmul Committee (Committee to Exterminate the Killers and Collaborators of 1971) held a Mock Trial of the war criminals of 1971. The massive public support to bring the war criminals to justice still exists. But little has been done to try these men and they have only gone on to gain political recognition. If they are allowed to participate in the forthcoming elections they will move to a heightened space of impunity.

Hana Shams Ahmed

Among the many memorable comments made by Barrister Mainul Husein during his tenure as an adviser to the caretaker government was the one he made about the trial of the war criminals. The law adviser said that some quarters were trying to obstruct the activities of the caretaker government by raising the issue of war criminals. He also went on to say that the governments who were in power before them, but did not try war criminals, should themselves be brought to trial for their inaction.

Marking a change in tone, Foreign Affairs Adviser Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury spoke to the UN Secretary General two months ago about 'a growing demand for the trial of the war criminals' and 'popular sentiment' for involving the UN in the process. Although the Army Chief and Chief Adviser both expressed the need for trials to begin, there has been nothing in the way of actual steps from this government.

This July, a group deceptively called 'Jatiya Muktijoddha Parishad' held a convention of freedom fighters at the Engineers Institute in Dhaka. When a freedom fighter Sheikh Mohammad Ali Aman (Sector 11, First Bengal Regiment, D Company, led by Colonel Taher) arrived there he found out that it was actually organised by supporters and activists of Jamaat-e-Islami and its student wing Islami Chhatra Shibir. Sheikh Mohammad was giving an impromptu interview to an ETV reporter where he protested such a farce. Shibir's goons swooped down on this freedom fighter, attacked him in front of cameras, and held him and the reporter captive for an hour until the media intervened.

These are members of the same group of people who said last October that there were 'no war criminals in the country' and Bangladesh's war of independence was nothing more than a 'civil war'. Jamaat's secretary general Ali Ahsan Mohammad Mujahid said to reporters that the charges against Jamaat-e-Islami were 'false' and 'ill-motivated'.

The UN Human Rights Commission in its 1981 report on the occasion of the 33rd anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UNHRC), stated that the genocide committed in Bangladesh in 1971 was the worst in history. An estimated three million Bangalis were killed by the Pakistani army with help from local collaborators (Razakars). The UNHRC report said, even if a lower range of 1.5 million deaths was taken, killings took place at a rate of between 6 to 12 thousand per day, through the 267 days of genocide. There were around 50,000 Razakars who opposed Bangladesh's independence. To abort the birth of Bangladesh they carried out a systematic cleansing operation of freedom fighters, students, teachers, intellectuals and religious minorities. a Quarter million women were raped.

War Crimes Facts Finding Committee (WCFFC), a research organisation, recently unveiled a list of 1,597 war criminals. Of those on the list, 369 are members of Pakistan military, 1,150 are their local collaborators including members of Razakar and Al Badr and Peace Committee, and 78 are Biharis. Jamaat's former Amir Golam Azam, present chief Matiur Rahman Nizami, Secretary General Ali Ahsan Muhammad Mojahid, Assistant Secretary General Muhammad Kamaruzzaman and AKM Yusuf, central committee members Delawar Hussain Sayedee, Abdus Sobhan, Abul Kalam Muhammad Yusuf and Abdul Quader Molla are among the high-profile Jamaat leaders on the list. Former BNP lawmakers Salahuddin Quader Chowdhury and Abdul Alim, and Anwar Zahid, a former minister during Ershad rule, are also on the list.

So what gives this group, which are internationally identified as war criminals (even in a recent issue of The Economist), so much impunity? From the public trials by the Nirmul Committee to the Sector Commanders' Forum and 37 years of general public demand and all the changes in government, this group seems to have gone from strength to strength and ultimately to the country's parliament and government cabinet. The CEC has declared that war criminals will not be allowed to take part in the election this year. But who will decide who are the war criminals ineligible for elections? The list made by the WCFFC is not considered official. The government has not produced or even endorsed any such list. That would mean that once these war criminals are allowed to participate in the elections they might automatically become immune from any further charges against them.

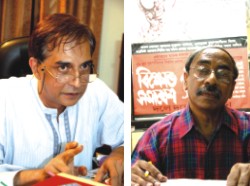

Dr Shahdeen Malik, an Advocate of the Supreme Court and Director of the School of Law at BRAC University, doubts that the present caretaker government will take any steps to bring the war criminals to justice but believes that if they do set up a platform it will become difficult for the next political government to stop the process. The legal process of trying the war criminals, he thinks, is fairly straightforward. “Two fundamental aspects make this law different from all other laws,” says Malik, “the procedural safeguards and the fundamental rights safeguards for an ordinary accused are not applicable for war criminals.”

|

| Dr Shahdeen Malik |

Shahriar Kabir |

Unlike other criminal trials, the International Crimes Tribunal Act 1973 says that hearsay evidence will be admissible in case of war crimes trials, or in other words, one can be convicted based on secondary evidence. In the rules of evidence section it says, 'A Tribunal shall not be bound by technical rules of evidence; and it shall adopt and apply to the greatest possible extent expeditious and non-technical procedure, and may admit any evidence, including reports and photographs published in newspapers, periodicals and magazines, films and tape-recordings and other materials as may be tendered before it, which it deems to have probative value' (section 19.1). It also goes on to say 'A Tribunal may receive in evidence any statement recorded by a Magistrate or an Investigation Officer being a statement made by any person who, at the time of the trial, is dead or whose attendance cannot be procured without an amount of delay or expense which the Tribunal considers unreasonable' (section 19.2) and 'A Tribunal shall not require proof of facts of common knowledge but shall take judicial notice thereof' (section 19.3). These in effect make the trial of the war criminals for the War of Liberation possible to carry out.

Malik believes that the seriousness of the crime and the seriousness of the implications for the society may not have been fully realised which has delayed the initiation of the process to try the war criminals. “It is the same way with corruption cases,” he says, “it is only now that we are understanding how damaging the corruption cases were. Our notion about corruption is more pronounced now than it was five years ago.”

As to why the caretaker government has so far been unwilling to undertake the responsibility of the trials Malik says, “Those who don't want the trials, as small as there number is, are in a position to turn it into a difficult and contentious issue for the current government and the nature of the current government is such that it does not have any political support, so it's not in a position to confront or take on political challenges. It would have been in a stronger position a year ago to take on this challenge, but at the very end of its tenure, it is unreasonable to expect it to be able to do it.”

Unfortunately, Malik says that not too many political parties will take up this issue, if they come to power with the support of Jamaat-e-islami or similar groups which were heavily involved in war crimes. “And it's not unlikely that the next government might depend on the political support of such groups,” says Malik, “if this government did start the ball rolling, then it would be very difficult for the next government even with support from the criminals to stop the process.” Journalist, filmmaker, human rights activist and the current convener of Ekatturer Ghatok Dalal Nirmul Committee Shahriar Kabir says that public opinion for the demand for the trial of the war criminals has not diminished ever since the mock trials at Shaheed Minar in 1992 to protest the granting of citizenship to Golam Azam. “Instead of trying Golam Azam the government placed sedition charges against 24 members of Nirmul Committee,” says Kabir, “unfortunately Jahanara Imam died two years later with the sedition charges on her head.”

“It is a shame,” says Kabir, “that despite Ziaur Rahman being a freedom fighter himself repealed the Collaborators Act and the BNP government came to power after forming a coalition with the war criminals.” Citing the 1972 Constitution as the most progressive he says Ziaur Rahman introduced Islam as the state religion and repealed the Collaborators Act. “The freedom fighters and the families of the martyrs have been demanding the trial of the war criminals over the years,” says Kabir, “AL, which has been the biggest political party supporting the committee's work, never took any steps to start the trial process.”

Unlike other criminal trials, the International Crimes Tribunal Act 1973 says that hearsay evidence will be admissible in case of war crimes trials, or in other words, one can be convicted based on secondary evidence.

When freedom fighters like Sheikh Mohammad Ali Aman can be humiliated and abused by the same group that term the War of Independence 'a civil war', it shows how strong this group's political foothold is. There has been a steady public demand for the trial of the war criminals, and although this demand is reflected in a ceaseless stream of newspaper headlines, they give a false impression that a trial is in the offing. Unfortunately, public pressure has been limited to seminars, symposiums, human chains and high-level meetings. The sector commanders and other groups are established in society and do not have the same confrontational attitude as grass root level freedom fighters and their families. The subaltern freedom fighters helped to free the country but do not enjoy the fruits of independence. But they are the only ones reminding the nation of unfinished business. Will Bangladesh see a resolution of the war crimes issues, or will it just wait for the last obstinate freedom fighter to perish. Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008 |