|

Chintito

Know thy Father

Chintito

For those who were born around 1953 (and please don't cheat), meaning they were about 14 or less in 1971, the events leading up to our War of Liberation may not have unfolded to them as LIVE history. For them there is some scope not to know who had what role to play, unless their parents were wholly (also read holy) honest with them. For them it may be possible to wrongly consider that a nationwide movement that even created waves in the Thames and ripples at the Sydney Harbour was triggered by some radio waves credited to both a civilian and an army officer, depending on the current political belief of the source. Alas! No other nation born of a bloody muktijuddho suffers from such naivete.

For the rest of the living population, such an act of knowledgeable ignorance (read gyan paapi) and wilful forgetfulness is unpardonable by that person's own conscience and punishable in a people's court, more so since the judiciary has taken into cognisance the life of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in declaring 15 August as the National Mourning Day.

For those to be so wretched as to be bracketed within the definition of the second paragraph above, such repetitive mention of Bangabandhu irritates them, their blood vessels become constricted and they suffer from falsehood fatigue. But such repetition of the facts has become necessary because of the onslaught of lies by the defeated forces of ekattur, some of who till today dream of a ‘one watan' with Pakistan while the vast majority of the people in that country remain busy with its inconsistent cricket, impeachment of military dictator Musharraf and befriending neighbouring India, not necessarily in that order.

For those who were born around 1953 (and the older ones whose memory need to be refreshed) here is a collage on Bangabandhu, as composed from word-for-word extracts from Syed Badrul Ahsan's Editorial 'Ground Realities: Agartala Conspiracy Case forty years on' (DS 18 June 2008), and 'Bangabandhu Life at a Glance' and Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury's 'Bangabandhu' in <www.bangabandhu.org>. Do not be surprised if it reads like the history of a nation yearning to be born.

Sheikh Mujib was born on 17 March 1920 in a middle class family at Tungipara in Gopalganj district.

His political life began as a humble worker while he was still a student. He was fortunate to come in early contact with such towering personalities as Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy and A K Fazlul Huq, both charismatic Chief Ministers of undivided Bengal. Adolescent Mujib witnessed the ravages of the Second World War and the stark realities of the great famine of 1943 in which about five million people lost their lives.

This was also the time when he saw the legendary revolutionary Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose challenging the British raj. Also about this time he came to know the works of Bernard Shaw, Karl Marx, Rabindranath Tagore and rebel poet Kazi Nazrul Islam. Soon after the partition of India in 1947 it was felt that the creation of Pakistan with its two wings separated by a physical distance of about 1,200 miles was a geographical monstrosity. The economic, political, cultural and linguistic characters of the two wings were also different. Keeping the two wings together under the forced bonds of a single state structure in the name of religious nationalism would merely result in a rigid political control and economic exploitation of the eastern wing by the all-powerful western wing which controlled the country's capital and its economic and military might.

In 1948 a movement was initiated to make Bangla one of the state languages of Pakistan. This can be termed the first stirrings of the movement for an independent Bangladesh. The demand for cultural freedom gradually led to the demand for national independence. During that language movement Sheikh Mujib was arrested and sent to jail. During the blood-drenched language movement in 1952 he was again arrested and this time he provided inspiring leadership of the movement from inside the jail.

In 1954 Sheikh Mujib was elected a member of the then East Pakistan Assembly. He joined A K Fazlul Huq's United Front government as the youngest minister. The ruling clique of Pakistan soon dissolved this government and Sheikh Mujib was once again thrown into prison.

In 1955 he was elected a member of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly and was again made a minister when the Awami League formed the provincial government in 1956. Soon after General Ayub Khan staged a military coup in Pakistan in 1958, Sheikh Mujib was arrested once again and a number of cases were instituted against him. He was released after 14 months in prison but was re-arrested in February 1962. In fact, he spent the best part of his youth behind the prison bars.

On 18 January 1968 the Pakistan government informed the country that thirty-five individuals had been charged with conspiracy to break up Pakistan and turn East Pakistan into an independent state with assistance from the Indian government. At the top of the list was Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, president of the East Pakistan Awami League and in detention since May 1966 under the Defence of Pakistan Rules. The implication was clear: Mujib had spearheaded the conspiracy. In stark terms, one of the more prominent of Bangali politicians had engaged in subterfuge and conspiracy to destroy the unity of the state of Pakistan!

But, at that point, one needed to go back to 1966. In that year of hope for Bangalis and growing apprehension for West Pakistan, Ayub Khan had warned that those who were propagating the Six Point programme of regional autonomy would be handled through the language of weapons. In early January 1968, subtle hints were being dropped about the imminent employment of such language. The Pakistan government went full-scale into a campaign to discredit those it had taken into custody. And a particular aspect of the campaign was an obvious move to finish off Sheikh Mujibur Rahman or bring his career to an end through convicting him as a traitor to the state of Pakistan.

The Agartala case marked the rise, in meteoric manner, of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the spokesman of the Bangalis. His courage of conviction where his principles were concerned and an abundance of self-confidence were made clear in the early stages of the trial. When a western journalist asked him what he expected his fate to be, Mujib replied with characteristic unconcern: “You know, they can't keep me here for more than six months.” In the event, he was to be a free man in seven months time.

On the opening day of the trial, Mujib spotted before him, a few feet away, a journalist he knew well. He called out his name, only to find the journalist not responding, obviously out of fear of all those intelligence agents present in the room. Mujib persisted. Eventually compelled to respond, the journalist whispered, “Mujib Bhai, we can't talk here . . .” And it was at that point that the future Bangabandhu drew everyone's attention to himself. He said, loud enough for everyone to hear: “Anyone who wishes to stay in Bangladesh will have to talk to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.”

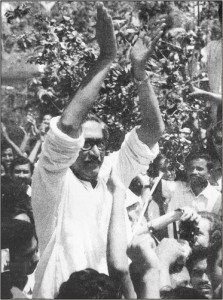

On February 22, 1969, Vice Admiral A.R. Khan, Pakistan's defence minister, announced the unconditional withdrawal of the Agartala Conspiracy Case and the release of all accused. The next day, a million-strong crowd roared its approval when Tofail Ahmed, then a leading student leader, proposed honouring Mujib as Bangabandhu, friend of Bengal. On February 24, he flew off to Rawalpindi to argue the case for the Six Points.

On December 5 of that year, at a meeting to remember Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Bangabandhu would inform Bangalis that henceforth East Pakistan would be known as Bangladesh. It was light unto the future. A nation was coming of age. A leader had arrived.

March 7, 1971 was a day of supreme test in his life. Nearly two million freedom loving people assembled at the Ramna Race Course Maidan, later renamed Suhrawardy Uddyan, on that day to hear their leader's command for the battle for liberation. The Pakistani military junta was also waiting to trap him and to shoot down the people on the plea of suppressing a revolt against the state. Sheikh Mujib spoke in a thundering voice but in a masterly well-calculated restrained language. His historic declaration in the meeting was: "Our struggle this time is for freedom. Our struggle this time is for independence." To deny the Pakistani military an excuse for a crackdown, he took care to put forward proposals for a solution of the crisis in a constitutional way and kept the door open for negotiations.

The crackdown, however, did come on March 25 when the junta arrested Sheikh Mujib for the last time and whisked him away to West Pakistan for confinement for the entire duration of the liberation war. In the name of suppressing a rebellion the Pakistani military let loose hell on the unarmed civilians throughout Bangladesh and perpetrated a genocide killing no less than three million men, women and children, raping women in hundreds of thousands and destroying property worth billions of taka. Before their ignominious defeat and surrender they, with the help of their local collaborators, killed a large number of intellectuals, university professors, writers, doctors, journalists, engineers and eminent persons of other professions. In pursuing a scorch-earth policy they virtually destroyed the whole of the country's infrastructure. But they could not destroy the indomitable spirit of the freedom fighters nor could they silence the thundering voice of the leader. Tape recordings of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib's 7th March speech kept on inspiring his followers throughout the war.

Forced by international pressure and the imperatives of its own domestic predicament, Pakistan was obliged to release Sheikh Mujib from its jail soon after the liberation of Bangladesh and on 10 January 1972 the great leader returned to his beloved land and his admiring nation.

He saw the plight of the country. Almost the entire nation including about ten million people returning from their refuge in India had to be rehabilitated, the shattered economy needed to be put back on the rail, the infrastructure had to be rebuilt, millions had to be saved from starvation and law and order had to be restored. Simultaneously, a new constitution had to be framed, a new parliament had to be elected and democratic institutions had to be put in place. Any ordinary mortal would break down under the pressure of such formidable tasks that needed to be addressed on top priority basis.

But at this critical juncture, his life was cut short by a group of anti-liberation reactionary forces who in a pre-dawn move on 15 August 1975 not only assassinated him but 23 of his family members and close associates. Even his 10 year old son Russel's life was not spared by the assassins. The only survivors were his two daughters, Sheikh Hasina later the country's Prime Minister - and her younger sister Sheikh Rehana, who were then away on a visit to Germany. But at this critical juncture, his life was cut short by a group of anti-liberation reactionary forces who in a pre-dawn move on 15 August 1975 not only assassinated him but 23 of his family members and close associates. Even his 10 year old son Russel's life was not spared by the assassins. The only survivors were his two daughters, Sheikh Hasina later the country's Prime Minister - and her younger sister Sheikh Rehana, who were then away on a visit to Germany.

In killing Bangabandhu, the conspirators ended a most glorious chapter in the history of Bangladesh but they could not end the great leader's finest legacy- the rejuvenated Bangali nation. In a fitting tribute to his revered memory, the present government has declared August 15 as the national mourning day. On this day every year the people would be paying homage to the memory of a man who became a legend in his own lifetime. Bangabandhu lives in the heart of his people. Bangladesh and Bangabandhu are one and inseparable. Bangladesh was Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's vision and he fought and died for it.

Journalist Cyril Dunn once said of him, "In the thousand - year history of Bangladesh, Sheikh Mujib is the only leader who has, in terms of blood, race, language, culture and birth, been a full - blooded Bangali. His physical stature was immense. His voice was redolent of thunder. His charisma worked magic on people. The courage and charm that flowed from him made him a unique superman in these times."Newsweek magazine has called him the poet of politics.

The leader of the British humanist movement, the late Lord Fenner Brockway once remarked, "In a sense, Sheikh Mujib is a greater leader than George Washington, Mahatma Gandhi and De Valera." The greatest journalist of the new Egypt, Hasnein Heikal (former editor of Al Ahram and close associate of the late President Nasser) has said, "Sheikh Mujibur Rahman does not belong to Bangladesh alone. He is the harbinger of freedom for all Bengalis. His Bengali nationalism is the new emergence of Bengali civilization and culture. Mujib is the hero of the Bengalis, in the past and in the times that are."

Embracing Bangabandhu at the Algiers Non-Aligned Summit in 1973, Cuba's Fidel Castro noted, "I have not seen the Himalayas. But I have seen Sheikh Mujib. In personality and in courage, this man is the Himalayas. I have thus had the experience of witnessing the Himalayas.”

Need you ask who the Father of the Nation is?

<[email protected]>

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2008 |