|

Cover

Story

Death at Work

Shamim Ahsan

The line between life and death can become extremely thin. On that Sunday night in Savar, the first few minutes after the nine-storied building caved in and became a huge heap of rubble were the most crucial. Perhaps the ones who died immediately were the luckier ones. At least it was better than being battered and bleeding and waiting for a death that would inevitably follow. The line between life and death can become extremely thin. On that Sunday night in Savar, the first few minutes after the nine-storied building caved in and became a huge heap of rubble were the most crucial. Perhaps the ones who died immediately were the luckier ones. At least it was better than being battered and bleeding and waiting for a death that would inevitably follow.

In that virtual grave, time goes slow, very slow. Many of the badly bruised who over the first few minutes have held fast onto life finally give in to Death's call. Those who finally escaped that horrific ordeal will have to live with the memory of being trapped under concrete with fellow workers dead or dying, with little hope of ever seeing the open sky again.

Twenty-four-year old Abdul Halim is one of around 84 who were rescued alive. A worker at the maintenance department, Halim, was on the ground floor when the building caved in at around 12.45 am. "It all happened within a second or two. Suddenly the floor beneath me broke open and I along with two others in the same room fell in the reserve tank. When I regained consciousness I thought I had been electrocuted. But the next moment I could feel my legs and the left part of my abdomen were entangled with pieces of bricks and concrete and I thought it must have been an earthquake," he recollects the first few moments after the crash. He was however more frightened than hurt and for some moments it seemed to him he was dead. After a while, they started clearing the debris and searching for a way out while shouting for help all the time. After around three hours, a group of army rescuers pulled all the three out, alive.

The path to escape was, however, much longer and more horrifying for knitting operator Ruhul Amin. He was on the sixth floor, working on a 7G machine. "Suddenly it seemed I fell some 50 feet down. A loose brick hit me and I found myself lying on my back, if it wasn't for that the falling roof would have crushed me to death. After the fall I saw, rather felt, there was a grave-like darkness all around, being stuck in bricks and disjointed parts of heavy machinery. The roof above me was only a few inches high, so I could not even sit, not to mention stand up. After sometime I started to crawl on my back, getting cuts and bruises all over my body. Passing every inch seemed to take an eternity," he says. The several hours' struggle finally ended when he discovered a ray of light. "Suddenly I seemed to have got great strength and forced myself towards the hole," he relates. After seven hours at 7.30am on Monday, Amin along with eight to ten others were pulled out by rescuers. Some five to seven more, who were alive till then, however, could not be rescued as they didn't have the energy to come near the rescue hole. "We talked all the while, now crying and now consoling each other. Someone kept on asking us to call Allah while someone continued to request us to get his thrashed left leg out from beneath a heavy machine. As I was coming out one Bazlu said, ' brother you don't need to get me out from here, you just send me some water. I will die happily if I can drink a glass of water". Amin's voice gets choked and he cannot continue. The path to escape was, however, much longer and more horrifying for knitting operator Ruhul Amin. He was on the sixth floor, working on a 7G machine. "Suddenly it seemed I fell some 50 feet down. A loose brick hit me and I found myself lying on my back, if it wasn't for that the falling roof would have crushed me to death. After the fall I saw, rather felt, there was a grave-like darkness all around, being stuck in bricks and disjointed parts of heavy machinery. The roof above me was only a few inches high, so I could not even sit, not to mention stand up. After sometime I started to crawl on my back, getting cuts and bruises all over my body. Passing every inch seemed to take an eternity," he says. The several hours' struggle finally ended when he discovered a ray of light. "Suddenly I seemed to have got great strength and forced myself towards the hole," he relates. After seven hours at 7.30am on Monday, Amin along with eight to ten others were pulled out by rescuers. Some five to seven more, who were alive till then, however, could not be rescued as they didn't have the energy to come near the rescue hole. "We talked all the while, now crying and now consoling each other. Someone kept on asking us to call Allah while someone continued to request us to get his thrashed left leg out from beneath a heavy machine. As I was coming out one Bazlu said, ' brother you don't need to get me out from here, you just send me some water. I will die happily if I can drink a glass of water". Amin's voice gets choked and he cannot continue.

A few square kilometres area surrounding the collapsed building is a human sea. Most of the huge contingent of security people taken from army, police, BDR, RAB are engaged in keeping the awaiting masses away from the site. Among thousands of curious viewers are men, women, and children wail inconsolably fearing the worst. Near the RAB control room, relatives are frantically making the same agonising query every few minutes, testing the patience of the officers in charge there. The entire place has become a site for mass mourning. Some cry loudly, others are numb with grief and say nothing. No one waiting out there gives up hope. But as hours pass by the expectation of finding the dear ones alive becomes slim. From Tuesday afternoon, the wait for survivors turns into a wait for dead bodies. The strong stench of rotting bodies spreads fast as if to announce the end of any sign of life under the debris. Every time a dead body arrives, everyone rushes to it; someone's wait finally comes to an end, but with that also ends the hope that has been kept alive for days. Some dead bodies arrive so decomposed that no one can recognise them and they end up as part of the list of the unidentified. A few square kilometres area surrounding the collapsed building is a human sea. Most of the huge contingent of security people taken from army, police, BDR, RAB are engaged in keeping the awaiting masses away from the site. Among thousands of curious viewers are men, women, and children wail inconsolably fearing the worst. Near the RAB control room, relatives are frantically making the same agonising query every few minutes, testing the patience of the officers in charge there. The entire place has become a site for mass mourning. Some cry loudly, others are numb with grief and say nothing. No one waiting out there gives up hope. But as hours pass by the expectation of finding the dear ones alive becomes slim. From Tuesday afternoon, the wait for survivors turns into a wait for dead bodies. The strong stench of rotting bodies spreads fast as if to announce the end of any sign of life under the debris. Every time a dead body arrives, everyone rushes to it; someone's wait finally comes to an end, but with that also ends the hope that has been kept alive for days. Some dead bodies arrive so decomposed that no one can recognise them and they end up as part of the list of the unidentified.

As one stands on the ruins of the collapsed nine-storey building one feels besieged by a strong sense of helplessness. The nine-storey building is now reduced to a three-storey-high pile of debris. The floors have fallen one on top of the other in such a way that the height between two floors is often less than one foot. The huge pieces of concrete slabs are woven by the tread of thick rod making the concrete mess all the more difficult to penetrate.

How It Caved In

Morshed Ali Khan

It is a classic story of negligence, defiance and disrespect. When the Spectrum Sweater Industries Ltd applied to the Savar Cantonment Board for permission to build a four-storey building four years ago, it provided the authorities with seven copies of building design along with a fee as required. Up to this point Spectrum followed the rules.

Having approved the design for a four-storey building, the army engineers waited for the Spectrum authorities to come to their office and collect six copies of the approved design. The six approved design copies are usually returned to the developer to enable engineers, architects and the construction supervisors to consult the design during construction.

But the Spectrum authorities never bothered to return to the Cantonment Board for the design copies. Instead, they launched their construction work on a plot measuring 9,374 square feet, a good portion of which encroached the adjacent natural canal called Baipol Khal. The four-storey building was soon completed, where heavy machinery occupied each of its floors with hundreds of male and female workers working day and night.

With a booming export operation, a year ago, the Spectrum authorities realised they urgently needed to expand their facility. And one Engineer Shamim, a so-called BUET graduate, was given the responsibility for the vertical expansion. The Spectrum authorities decided that another five stories would be needed to house their expanding industry.

Seeing a rising demand for its products abroad, the company was in such a hurry to expand that it never bothered to seek any permission from anyone. According to insiders, the owner of the Spectrum Sweater Industries Ltd clearly banked on his "influence over everything and everybody".

An extra workforce was engaged to complete the extra five floors within a "very short time".

Now new machinery filled each floor of the just-completed nine-storey building. The industry freshly employed hundreds more to work round-the-clock shifts to boost their export, totally oblivious to the fact that they were sitting on a deadly time bomb.

It was in the early hours of April 11 that the entire building caved in like "a house of cards" crushing to death "several hundred innocent workers", who were doing night shift.

According to structural design engineer AKM Jahangir Alam and architect Iqbal Habib, who inspected the site along with this correspondent, the foundation of the nine-storey Spectrum building had totally failed. Jahangir Alam, having closely examined the pattern of the fall said the foundation of the building failed on the side of the canal, which immediately shifted the load of the 81,000 square feet of concrete, masonry and the huge number of machinery on one side Floor after floor crumbled on top of one another, each slightly sliding towards the Baipol Khal -- a strong indication that the foundation failure started on that side.

Although, a case under the section 338/304Ka of the penal code was lodged by the Officer in-charge of Savar thana, Nazrul Islam, on April 12, implicating the owner in "murder by negligence", the Detective Branch of police failed to question anyone of the Spectrum Sweater Industries Ltd. The influential owner of the company probably rightly banked on his confidence, knowing well that he could get away with anything.

|

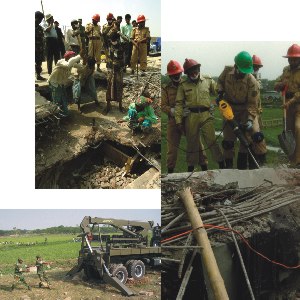

Even after 38 hours into the tragic collapse, the rescue operation seems to have made little progress. A group of army personnel are trying to make a hole with a drill that looks ridiculously tiny compared to the thick huge slabs it is trying to penetrate. A little further up four fire service men are struggling with a hand-driven rotary saw, equally scanty considering the job it is pitted against, to cut through the robust concrete masses.

A little towards the north, two day labourers are fighting with a big nail held by one while the other one strikes with a big handled hammer exactly the way we see pucca roads being dug out. On the ground a crane, like the one we see in the dump yards, is posted and is being used after long intervals and to little effect. But all these efforts, and particularly the tools that are being used, appear absurdly inadequate. The magnitude of the destruction makes the rescue operation look pathetically insufficient. Selim Newaj Bhuiyan, Deputy Director, Dhaka Division, Fire Brigade, spells out the action plan of the biggest rescue operation in history: "We will cut through till the ground floor and after we cut open a floor we are going to use search lights to see if there is anyone alive or dead." After about 38 hours a hole of 5 ft by 4 ft has been opened in the ninth floor. As one remembers the fact that around 300 workers were working on that fateful night and most of them are still believed to be trapped under this rubble one cannot but feel helpless at the pace the rescue work is progressing. When every second counts, the action plan seems rather naive, particularly the way the operation is going on. It seems it will take an eternity to complete the job.

"Why can't you remove the huge concrete instead of taking years to cut through the floors, that too, with tools that seem fit only for road construction?" This is the question on every bystander's lips. "It's natural for you people to think that way. But if I try to remove a piece of concrete slab, the balance of the piles of rubbles might be affected, triggering a change in the whole shape of the pile of rubble which might just kill those who are still alive out there. So, we are being extra cautious to avoid a further collapse and more deaths due to that," Selim explains. "We are working with whatever expertise we have and whatever machinery we have in our possession." Selim also points out that a devastation of this scale is unprecedented not only in his close-to- 30-year career, but also in the history of Bangladesh.

His boss, Director General of Fire Brigade, Brig. General Rafiqur Rahman, doesn't have much else to say. As he arrives on the scene on Tuesday afternoon to monitor the rescue operation, he doesn't hide his worry when asked about how much time it might take to complete their operation. " I don't know exactly, perhaps several days. But our people are working hard as you can see and not without some risk." He emphasises on the last word. His boss, Director General of Fire Brigade, Brig. General Rafiqur Rahman, doesn't have much else to say. As he arrives on the scene on Tuesday afternoon to monitor the rescue operation, he doesn't hide his worry when asked about how much time it might take to complete their operation. " I don't know exactly, perhaps several days. But our people are working hard as you can see and not without some risk." He emphasises on the last word.

He refuses straight-out that they don't have the right equipment under their disposal for such a salvage operation. He points to some half a dozen heavy tank-like machines stationed a little away from the destruction site and explains that these machines cannot be used because the surrounding marshy land as well as the absence of any roads are not allowing them be brought near the spot and therefore are lying unused. When asked if he thinks the building collapsed due to improper construction, he says that his department is neither empowered to investigate it nor have the expertise to determine it. "It is the job of the engineers who will scrutinise the design, drawing and other related things like piling to decide it," he adds.

Interestingly, whatever modern machinery were being used were there only by a stroke of luck. Showing the rotary saw, tripping hands, a drill, a reciprocating saw, Parimal Chandra Kundu, fire service assistant instructor, reveals that these were donated by the US government only last month for training in a post earthquake situation. He admits that this machinery is inadequate to handle such a massive collapse. If anything, the tragic building crash has once and for all exposed how badly equipped we are in terms of both technology and skilled manpower regarding rescue operations only of one multi-storey building. Just imagine what we will do in case of even a mild earthquake in Dhaka crammed with multi-storied structures? Interestingly, whatever modern machinery were being used were there only by a stroke of luck. Showing the rotary saw, tripping hands, a drill, a reciprocating saw, Parimal Chandra Kundu, fire service assistant instructor, reveals that these were donated by the US government only last month for training in a post earthquake situation. He admits that this machinery is inadequate to handle such a massive collapse. If anything, the tragic building crash has once and for all exposed how badly equipped we are in terms of both technology and skilled manpower regarding rescue operations only of one multi-storey building. Just imagine what we will do in case of even a mild earthquake in Dhaka crammed with multi-storied structures?

Now, the real question is what exactly caused the collapse? So far two main reasons have come up as possible causes for the collapse -- the building collapsed(as was claimed by the garments owners through a press release), because the boiler burst or the building caved in because of major faults in the construction. As is always the case, the five-member RAJUK investigation committee, formed right after the incident, is yet to make any headway into the incident. Though they were tasked to submit a report within three days, around six days after the incident, they are nowhere near solving the case. According to a Prothom Alo report, the progress in the investigation was hampered as it doesn't have any boiler experts and the committee has reportedly written to the Industry ministry and Fire Brigade for a boiler expert. Though they don't want to give their final verdict until the rubble is cleared, depending on their investigation they have so far done, particularly from the overwhelming evidence they have collected and examined, the committee believes the accident was caused due to faulty construction. Now, the real question is what exactly caused the collapse? So far two main reasons have come up as possible causes for the collapse -- the building collapsed(as was claimed by the garments owners through a press release), because the boiler burst or the building caved in because of major faults in the construction. As is always the case, the five-member RAJUK investigation committee, formed right after the incident, is yet to make any headway into the incident. Though they were tasked to submit a report within three days, around six days after the incident, they are nowhere near solving the case. According to a Prothom Alo report, the progress in the investigation was hampered as it doesn't have any boiler experts and the committee has reportedly written to the Industry ministry and Fire Brigade for a boiler expert. Though they don't want to give their final verdict until the rubble is cleared, depending on their investigation they have so far done, particularly from the overwhelming evidence they have collected and examined, the committee believes the accident was caused due to faulty construction.

As far as the boiler-bursting theory is concerned, an interpretation the building owners are pushing hard to establish, apparently to rid themselves of the crime of low quality construction, has been rejected both by a survivor as well as the investigation committee. While talking to a TV crew after his miraculous survival from the death trap, Polash, a boiler assistant who was posted near the boiler when the building caved in, claims firmly that the boiler did not burst. Lying on a bed in Savar CMH with bruises on his face and lower part of his legs bandaged, he says: "I was lying pretty close to the boiler when the building collapsed. Had the boiler burst, I would have certainly felt the boiling water that would come out from the burst boiler, but I am sure nothing of that sort happened." Besides, the investigation committee has also found the boiler in its original position. As far as the boiler-bursting theory is concerned, an interpretation the building owners are pushing hard to establish, apparently to rid themselves of the crime of low quality construction, has been rejected both by a survivor as well as the investigation committee. While talking to a TV crew after his miraculous survival from the death trap, Polash, a boiler assistant who was posted near the boiler when the building caved in, claims firmly that the boiler did not burst. Lying on a bed in Savar CMH with bruises on his face and lower part of his legs bandaged, he says: "I was lying pretty close to the boiler when the building collapsed. Had the boiler burst, I would have certainly felt the boiling water that would come out from the burst boiler, but I am sure nothing of that sort happened." Besides, the investigation committee has also found the boiler in its original position.

The nine-storey Spectrum Sweater Industries and the four-storey Shahriar Fabrics buildings were joined together and both of them are owned by Shariar Sayed Hossain. The four-storey Shahriar Fabrics building that stands along the main road was built earlier and is still in one piece. The collapsed nine-storey building of Spectrum Sweater Industries in Savar was built defying the existing rules and regulations. RAJUK Chairman Md Shahid Alam has already confirmed that the garment building in question didn't have their approval. Neither did it have approval of the fire Brigade and Environment Department as the rule requires for such construction. The nine-storey Spectrum Sweater Industries and the four-storey Shahriar Fabrics buildings were joined together and both of them are owned by Shariar Sayed Hossain. The four-storey Shahriar Fabrics building that stands along the main road was built earlier and is still in one piece. The collapsed nine-storey building of Spectrum Sweater Industries in Savar was built defying the existing rules and regulations. RAJUK Chairman Md Shahid Alam has already confirmed that the garment building in question didn't have their approval. Neither did it have approval of the fire Brigade and Environment Department as the rule requires for such construction.

As a news story the Savar collapse may soon lose its space in the front pages with newer disasters taking over. A Prothom Alo story states that in the last 15 years, around 400 workers have died in garment factory mishaps. The Savar tragedy is the worst such disaster in our history. The most mortifying realisation is that all these 'accidents' were the result of extreme negligence. The latest one exemplifies the utter disregard for the people whose blood and sweat help to bring about the affluence that these employers enjoy. Of course, there are examples of fair employers who try their best to take care of their workers. But for the most part, workers are seen as another form of machinery that is needed to make a product. The compensations offered to the victims' families have been ludicrous and humiliating. So far, the owner of the faulty building has not been arrested because the police cannot find him. Again it is class that makes the difference, allowing the privileged to escape responsibility for what amounts to murder due to negligence, and the underprivileged to go on being exploited and denied their basic rights. Especially the right to work and stay alive.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005

|

| |