| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 08| February 24, 2012 | |

|

|

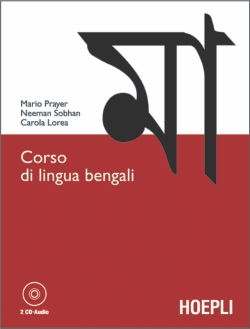

A Roman Column Saving Bangla Neeman Sobhan On the eve of Ekushey, here in Rome, I am preparing to pay my respecst to the language martyrs of 1952 at our Roman Shaheed Minar monument tomorrow, by laying there an advance copy of the first book of Bangla Language for Italians ever to come out of an important academic publishing house in Italy. This book, complete with audio-CD's, is published by Hoepli as part of a series of language books for Italians, and has been the joint fruit of two years incessant labour by myself, my Italian colleague and Professor of Bangla at La Sapienza where we teach, and a student of ours.

This book, which we have titled simply 'MA' is my offering to my mother tongue on this year's International Mother Language day. I feel as if I were in my small way a part of the language movement of the past; and yet, I also feel a certain disenchantment, a feeling that perhaps, we Bengalis need another language movement. This time, a less revolutionary and more evolving and dedicated movement to save, nurture and consolidate our inheritance. The other day, I had taken a group of my Italian students of Bangla to the covered fresh produce market near La Sapienza university's Faculty of Oriental Studies, where I teach. As always, I took advantage of the many Bengali stall keepers and encouraged my students to chat with them and practise their newly acquired language skills. They were shy, so I asked Rokib, who was brandishing stalks of locally produced red spinach and coriander leaves, if he could start the conversation. "Kaimon asen?" He nodded to Giuseppe and Francesca. They looked at me, and I whispered to them, "He meant 'kaimon achen' and used the dialect form 'asen'. Recognise this form, but try not to use it, yet." Rokib overheard me. Smilingly, and with perfect ease, he switched to speaking the standardized form of Bangla that we teach in class, and which we tell our students to expect to be used in the media, public institutions, formal speech and among the educated. We also warn our students that the reality outside the classrooms will reveal a less elegant, more earthy and informal language in use on the streets, even among the educated. But during the learning process we insulate them from it until they can distinguish both forms. While a conversation continued between Rokib and my Italian students, another Bengali man, simple and unprepossessing in attire, came out of nowhere and approached me: "Apa, are you teaching these Italians to speak Bangla?" I nodded. "Why?" He asked with irony written all over his unsmiling face. Before I could wipe the bafflement from mine and make an appropriate response to him, he continued: “What I mean is, why waste your time teaching these foreigners to speak such good Bangla when what is urgently required is that someone teach us Bengalis to speak proper Bangla! Have you noticed how low the standard of our spoken Bangla has sunk? Day by day we are destroying and forgetting our own mother tongue. Do we deserve a Bhasha Dibosh, a language day? Do we who cannot pronounce the language, deserve to be its custodians?” I gazed at the man, surprised by the passion in his voice, and the concern he felt for a language that he obviously loved enough to be so angry. The sum total of his outrage was something I could not deny: day by day an indifferent and rustic kind of Bangla is taking over as the only kind of Bangla in use in most public spheres. True, I thought. Few people have made such a lot of fuss about their mother tongue as the Bengalis have, marching on the streets, shouting themselves hoarse, shedding blood and tears. Yet, as soon as they wrested the proper status, as well as a land for their language, they seem to have abandoned it at the street corner as if it were nothing more than a heap of torn pamphlets and banners fluttering around the alleys to be trampled on after the procession for the mother tongue had passed and the demonstrators gone home. I used to take pride in telling my students that Bangladesh is the land that gave the Bengali language a home, a safe haven. But watching the steady degeneration of spoken everyday Bengali, I feel it might have flourished better if we still had to fight for it on a daily basis, competing for attention against other languages. The mangled pronunciation of some basic letters of spoken Bengali in Bangladesh today makes it not really the refined language of educated urbane speakers, but mostly a concoction of dialect and rough countrified speech patterns. There is nothing wrong with dialect. Everyone has a right to it, but it should not become the predominant form of language in any upwardly mobile society that has aspirations towards refinement and culture. I live in Italy, a country which for centuries was splintered into hundreds of city states with as many dialects. It is only recently, 150 years ago, that the nation saw unification. Dialects have thrived locally, but at the national, urban and public level everyone speaks and uses the standard Italian of Dante taught in schools, used in offices and public institutions, the media and the arts, by politicians, students and taxi drivers alike. The mark of an educated, sophisticated person is the language he uses to communicate with others. In Bangladesh it is sad to see the diminishing of this class. Few seem to speak the language of standardised correct pronunciation. Entire letters and sounds from the alphabet have vanished or morphed into totally different sounds: 'CH' no longer exists and has become 'S' (so 'Chatro' or student is regularly pronounced 'satro!) while 'J' has become 'Z' (so 'Janala' or window is now 'zanala' and 'kaaj' or work is 'kaaz'!) The danger of mispronouncing certain letters and sounds is that if it is not corrected, this creeps into the written language of transliterated English, and gets further entrenched into Bangla speech. One lady with the lovely name 'Chobi' as in picture or portrait, actually writes her name in English as 'Sobi'! This in turn led an Italian student learning Bangla to spell her name in Bangla with a dontoshshaw! A TV channel has corrupted the word for fish in Bangla from Mach to Mas, and writes its name in English as 'Masranga'. The 'PH' sound which is the aspirated form of 'P' has turned into 'F', thus a stall selling the street food 'Phuchka' was spelt 'Fuska'! I can go on and on, but it would be an exercise in futility. I really think it is time to start another language movement. This time an andolon to safeguard the purity of our language, to save Bangla from ourselves! We need to prevent the erosion of our language from the flood of countrified speech habits that is washing away many of the distinctions between sounds in our alphabet. I don't want to see my language corrupted to the extent that we have the same sound 's' for both the non-aspirated 'ch' as in 'chaa' (tea) as well as the aspirated 'ch' as in 'chele' (boy). An un-bengali monster called 'Zaw' has risen from the deep and swallowed our 'Jaw'. Where are the life-guards of the language? It is urgent that we create teachers who are trained to be conscious about how our beautiful language ought to be pronounced, and that we all make it our responsibility to point out and correct the mis-pronunciations rampant around us, especially when they are reflected in their English transliterations. Today, I will not touch on another issue, an even more serious one of transliterating wrongly from Arabic, thus confounding the 'Jeem' with a 'Zed' and debasing Allah's name from say, Jalil to Zaleel (the humiliated).We need to discuss another day how to solve these not unsolvable problems along with the kidnapping of the English letter 'V' to represent wrongly the Bangla 'BH' sound. But for today, I feel, it is enough that we try to save even the sixth and seventh Bengali consonants, the 'Chaw' and 'Chhaw' and save the Borgiyo and Ontostho 'Jaw' from extinction in oral speech! I sincerely feel that the movement for Shuddho or Correctly spoken Bangla bhasha has to start. Now. Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |