|

Cover

Story

The

Artist of

People's Struggle

Mustafa

Zaman

Zainul

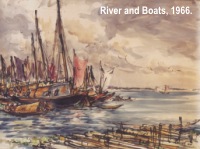

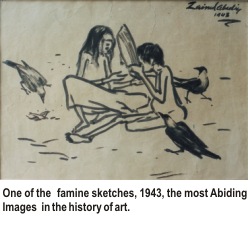

Abedin is the name eternally tied up with the unforgettable

Famine Sketches, and with images of humans toiling to move

a bull-cart stuck in the mud, which he titled "Struggle".

But it was also paintings like "Monpura" -- the

mural-like 96 cm-long scrawl that encapsulated the aftermath

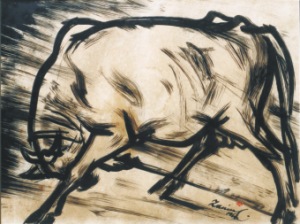

of the cyclone of 1970, and that image of "Rebellion"

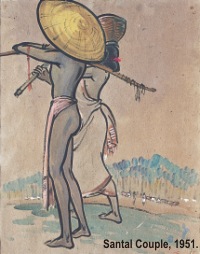

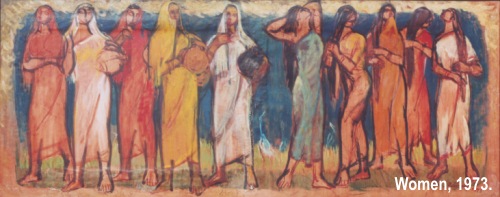

depicting a raging bull, as well as many other images of boats,

women and Santal life that makes him undoubtedly the "pioneer"

in art in the true sense of the word. Many claim that he left

behind few masterpieces. Most of his detractors insist that

the Famine Sketches are the only significant bulk of work

that Zainul ever produced. All things said and done, the name

Zainul Abedin still retains the vitality and verve that existed

during the artist's lifetime. The legend lingers on; the genius

whose fame had once splashed across the Indian subcontinent

and made the artist stand out among his peers, is beaming

up all the signs of his luminosity to today's viewers through

his magnificent works. Zainul

Abedin is the name eternally tied up with the unforgettable

Famine Sketches, and with images of humans toiling to move

a bull-cart stuck in the mud, which he titled "Struggle".

But it was also paintings like "Monpura" -- the

mural-like 96 cm-long scrawl that encapsulated the aftermath

of the cyclone of 1970, and that image of "Rebellion"

depicting a raging bull, as well as many other images of boats,

women and Santal life that makes him undoubtedly the "pioneer"

in art in the true sense of the word. Many claim that he left

behind few masterpieces. Most of his detractors insist that

the Famine Sketches are the only significant bulk of work

that Zainul ever produced. All things said and done, the name

Zainul Abedin still retains the vitality and verve that existed

during the artist's lifetime. The legend lingers on; the genius

whose fame had once splashed across the Indian subcontinent

and made the artist stand out among his peers, is beaming

up all the signs of his luminosity to today's viewers through

his magnificent works.

Back in his early years in Kolkata (then Calcutta)

his supreme artistic abilities immortalised him and placed

him at the apex of the brewing art movements. But what really

made him out of the ordinary among a myriad of other talented

young artists? Each had an ingenious way of representing the

reality that they were a part of. Some, like the already famous

art gurus, Nandalal Basu or Jamini Roy, had an inclination

to draw on the tradition, but Zainul had an empathy for the

masses that had rarely been expressed in the visual arts,

let alone used to make bold artistic statements.

In

the European art scene, Daumier, Goya and Hogarth's efforts

predate Zainul's forays into the sufferings of people. However,

noone had articulated the passion for the masses with the

disarming simplicity that Zainul brought into play in his

famine sketches. And the dignity of the toiling men, too,

had never been expressed in a language that would leave such

a lasting impression in the collective psyche, as did Zainul's

paintings. Perhaps he is the only artist whose work has been

reproduced by self-taught denizens strewn across the country.

The acclamation that he received certainly broke boundaries

of class; his "Struggle" even ended up being on

the back of scooters and rickshaws. No 'high-art' exponent

had this luck. Many may not even look at it as such. But,

Zainul obviously did belong to the ilk that professed to have

put their ingenuity to the task of making images that had

socio-political as well as artistic relevance. His was an

aesthetic sense that was inclusionary. In fact, when he came

to Dhaka after the partition of India to establish an art

institution, he led a number of artists to galvanise an art

scene that doted on the reality of the then East Bengal, the

eastern province of newly independent Pakistan. He fertilised

the ground by practising and professing a mode of art that

never severed its link with the "people of the soil"

to set a precedent for the younger generation artists. In

the European art scene, Daumier, Goya and Hogarth's efforts

predate Zainul's forays into the sufferings of people. However,

noone had articulated the passion for the masses with the

disarming simplicity that Zainul brought into play in his

famine sketches. And the dignity of the toiling men, too,

had never been expressed in a language that would leave such

a lasting impression in the collective psyche, as did Zainul's

paintings. Perhaps he is the only artist whose work has been

reproduced by self-taught denizens strewn across the country.

The acclamation that he received certainly broke boundaries

of class; his "Struggle" even ended up being on

the back of scooters and rickshaws. No 'high-art' exponent

had this luck. Many may not even look at it as such. But,

Zainul obviously did belong to the ilk that professed to have

put their ingenuity to the task of making images that had

socio-political as well as artistic relevance. His was an

aesthetic sense that was inclusionary. In fact, when he came

to Dhaka after the partition of India to establish an art

institution, he led a number of artists to galvanise an art

scene that doted on the reality of the then East Bengal, the

eastern province of newly independent Pakistan. He fertilised

the ground by practising and professing a mode of art that

never severed its link with the "people of the soil"

to set a precedent for the younger generation artists.

Murtaja

Baseer, a prominent artist who was a student of Zainul, says,

"One can easily draw a comparison between Zainul and

Jasimuddin. Both are recognised at the drop of their names

all around Bangladesh. Zainul too felt a strong affinity towards

the rural masses." In return, he was loved back, and

18 years after his death, in the year of his 90th birthday,

he still remains the most recognised and revered artist of

his land. Murtaja

Baseer, a prominent artist who was a student of Zainul, says,

"One can easily draw a comparison between Zainul and

Jasimuddin. Both are recognised at the drop of their names

all around Bangladesh. Zainul too felt a strong affinity towards

the rural masses." In return, he was loved back, and

18 years after his death, in the year of his 90th birthday,

he still remains the most recognised and revered artist of

his land.

"During the famine of 1943, Zainul suddenly

discovered that the peasants, the fishermen and women that

he identified with were rotting in the pavements of Kolkatta.

He was horrified that they came to the city to die,"

Baseer throws light on the working of the maestro's mind.

What Zainul did was not mere documentation

of the famine. I the sketches the signs of famine manifested

in all its sinister attributions through the emaciated and

skeletal figures of a population fated to die of starvation

in a man-made plight. Zainul depicted the inhuman saga with

an intense human passion only possible for a great mind.

As the drawings of the famine-struck men,

children and women remains a cornerstone in the history of

art in this region, they helped shape an artist's path. Zainul's

conviction kept him forever in sympathy with the poor. Zainul

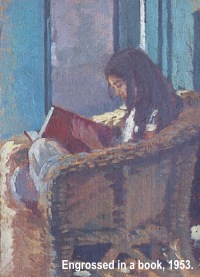

may have rendered damsels in leisure; doing their coiffure,

or while bathing in the river, but his idiom was distinctly

laden with a strong sense of reality. His gaze was never 'disinterested'

or 'abstract.' Beauty he sought, beauty he achieved in many

of his paintings without sacrificing the struggle that is

associated with the lives he depicted.

Abul

Monsur, a noted art critic, writes, "If one considers

the rural people's life and what they have created as a whole

in the form of the very fabric of their lives' saga -- one

will realise the originality and the appeal of Zainul's creativity."

The notion of an artist internalising the human experiences

by remaining at a human level was unique, and Zainul remains

the pioneer by forging this marriage between life and art. Abul

Monsur, a noted art critic, writes, "If one considers

the rural people's life and what they have created as a whole

in the form of the very fabric of their lives' saga -- one

will realise the originality and the appeal of Zainul's creativity."

The notion of an artist internalising the human experiences

by remaining at a human level was unique, and Zainul remains

the pioneer by forging this marriage between life and art.

His death on May 28 in 1975, was sudden. Although

he was suffering from cancer of the lungs since December of

the previous year, the time when the disease was detected

after he fell ill and was flown to London for treatment, Zainul's

death at the age of 62 caught many by surprise. The outpouring

of grief on the day he died was unprecedented.

Since

his death, little has been done to advance his aesthetic goal.

With the leading man absent, his works too remained hidden

from the public gaze. Except for the January show of 1977

at the Shilpakala Academy that coincided with the publication

of a book on the master by Nazrul Islam, an art writer, the

sightings of his real works have been sparse. In a handful

of group shows and in the regular display at the National

Museum his admirers had the chance to look at some select

paintings. Since

his death, little has been done to advance his aesthetic goal.

With the leading man absent, his works too remained hidden

from the public gaze. Except for the January show of 1977

at the Shilpakala Academy that coincided with the publication

of a book on the master by Nazrul Islam, an art writer, the

sightings of his real works have been sparse. In a handful

of group shows and in the regular display at the National

Museum his admirers had the chance to look at some select

paintings.

The current giant of a show organised by the

consortia of Bengal Foundation, Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy

and the Bangladesh National Museum has put an end to that

situation. With the help of Zainul's widow, Jahanara Abedin,

these three organisations have pulled off, at last, a retrospective

of the master artist of Bangladesh. This is a landmark in

the history of curating; no retrospective show of this proportion

has ever been envisaged before.

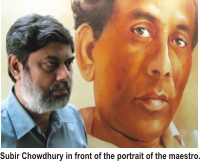

"Our

intention was to re-introduce Zainul through his works--the

pieces many might've seen in reproduction but never in original

form. His big paintings like Nobanya or Monpura succinctly

tell of his artistic might," exclaims Subir Chowdhury,

the former Director of the Department of Fine Arts at the

Shilpakala Academy who now remains at the helm of Bengal Gallery

as its director. "Our

intention was to re-introduce Zainul through his works--the

pieces many might've seen in reproduction but never in original

form. His big paintings like Nobanya or Monpura succinctly

tell of his artistic might," exclaims Subir Chowdhury,

the former Director of the Department of Fine Arts at the

Shilpakala Academy who now remains at the helm of Bengal Gallery

as its director.

Dispersed in three different venues, the show

of 573 original works has been launched simultaneously at

the National Gallery of Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, at

the National Museum and Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts on December

12. There are side-shows and events that centre around this

main exhibition that will last till January 7, 2005.

Zainul is the first artist to have been given

such an honour at the 'national level.' "For many years

people have been unhappy about the fact that there has been

no effort to showcase Zainul's works. The dominant tone was

that there has been effort at the national level for Abbas

Uddin, the legendary singer, but the man we call the 'father'

in the field of fine arts has never been a subject of a full-blown

solo show," notes Subir Chowdhury.

However,

while in the hot seat of the Shilpakala Academy, Chowdhury

and his colleagues toyed with the idea of having a grand retrospective

of the maestro. In fact, Shiplakala Academy did arrange for

the first solo after Zainul's demise. On January 1977, a show

of his works in the former national gallery was the first

tribute at a national level. "The book that was published

on the occasion was the first major publication on Zainul.

And it was planned and executed at very short notice,"

remembers Chowdhury who joined the Academy in 1975. However,

while in the hot seat of the Shilpakala Academy, Chowdhury

and his colleagues toyed with the idea of having a grand retrospective

of the maestro. In fact, Shiplakala Academy did arrange for

the first solo after Zainul's demise. On January 1977, a show

of his works in the former national gallery was the first

tribute at a national level. "The book that was published

on the occasion was the first major publication on Zainul.

And it was planned and executed at very short notice,"

remembers Chowdhury who joined the Academy in 1975.

For

the present show, a lot of brain-storming as well as time

have been invested. "Planning started as early as last

May. I was still with the Shilpakala Academy and on July 7th

a formal meeting among the three organisations were arranged.

The family of Zainul Abedin was also there. It was Jahanara

Abedin, who played a pivotal role and it was the Bengal Gallery

that was ready to pay the bills," explains Chowdhury. For

the present show, a lot of brain-storming as well as time

have been invested. "Planning started as early as last

May. I was still with the Shilpakala Academy and on July 7th

a formal meeting among the three organisations were arranged.

The family of Zainul Abedin was also there. It was Jahanara

Abedin, who played a pivotal role and it was the Bengal Gallery

that was ready to pay the bills," explains Chowdhury.

To give the event national significance, assistance

was sought from the government of Bangladesh. "On August

14th we met with the Cultural Minister, who gave us the green

light," Chowdhury notes. He then goes on to reflect on

the maestro's artistic proclivities. He says, "He had

immense interest in craft and the craft people of Bangladesh.

In fact, he had this idea of a fine art that was already stilted

on the traditional practices of the land that is kept alive

in our craft. To pay homage to his love for craft we have

arranged for a 'Karumela' (craft fair) that strives to show

the present state of craft."

Crafts

were significant to him, they even moulded some of his stylistically

rigorous paintings. During the mid 50s he tried his hands

at folk-art motifs-derived images. In an interview with Nazrul

Islam, Zainul once vented his dissatisfaction over a string

of the first and second batch students being caught in the

trap of 'modern trends' that defied any link with the cultural

brio that characterises the land and people. Crafts

were significant to him, they even moulded some of his stylistically

rigorous paintings. During the mid 50s he tried his hands

at folk-art motifs-derived images. In an interview with Nazrul

Islam, Zainul once vented his dissatisfaction over a string

of the first and second batch students being caught in the

trap of 'modern trends' that defied any link with the cultural

brio that characterises the land and people.

The man who was known for his art and compassion

for his people, lived a simple life. Born in a humble abode

of a "minor police official" he had an even humbler

upbringing. Though his grand father, a petty trader, lived

in Mymensingh, Zainul was born in Kishoreganj, where his father

was posted at the time.

His mother Jainabunnessa came from a family

that "hadn't yet welcomed modern education," writes

Syed Azizul Haque in the preface of the catalogue that has

been put out on the occasion of the retrospective show.

The

periodic transfer of his father from one place to the other

exposed young Zainul to mofussil towns of Mymensingh

and to its rural rustic life. His peripatetic father, Sheikh

Tamizuddin Ahmed settled in Mymensingh town proper in 1926.

He built a small house for the family. It was in Mymensingh

that the cultural firmament finally brushed on to young Zainul. The

periodic transfer of his father from one place to the other

exposed young Zainul to mofussil towns of Mymensingh

and to its rural rustic life. His peripatetic father, Sheikh

Tamizuddin Ahmed settled in Mymensingh town proper in 1926.

He built a small house for the family. It was in Mymensingh

that the cultural firmament finally brushed on to young Zainul.

As a high-school student, he developed the

knack for drawing and painting; it almost came naturally to

him. Rote learning could never interest him. In Mymensingh

he found his peers among a few 'like-minded friends, among

them Ashish Ghatak (1914-1974), brother of the celebrated

film-maker Ritwik Ghatak (1925-1976), and Premranjan Dasgupta,

owner of a photographic studio which was a meeting ground

for Mymensingh's artistically inclined youth," writes

Haque.

In

1932, upon completion of high school, young Zainul left for

Art College in Kolkata. He took the admission test at the

then Calcutta Art College in 1932, and topped the merit list.

It was Mukul Dey, an eminent artist and the principal of the

college, who recommended Zainul for the "District Board

stipend," which was duly awarded to him. Soon, the budding

young artist made a name for himself for his studiousness;

he devoted much of his time in drawing and painting. In

1932, upon completion of high school, young Zainul left for

Art College in Kolkata. He took the admission test at the

then Calcutta Art College in 1932, and topped the merit list.

It was Mukul Dey, an eminent artist and the principal of the

college, who recommended Zainul for the "District Board

stipend," which was duly awarded to him. Soon, the budding

young artist made a name for himself for his studiousness;

he devoted much of his time in drawing and painting.

Zainul as a student lived in a boardinghouse

to cut down on expenses. It was during his advanced years

when he started contributing cartoons and illustrations to

newspapers to earn money that helped pay his own bills and

to send some to cover the expense of his younger siblings.

Later he moved into a flat, probably the one that Jahanara

Abedin remembers as the first home to the newly wed couple

in Kolkata.

"At

the Tarok Dutta Road house he used to cook, as I told him

earlier that I had no expertise in that area," recalls

Jahanara Abedin.

They

got married in October 1946. "It was Shafiqul Amin, the

elder brother of my sister's husband, who was the matchmaker.

We came to know that 'Zainul was a good man and what others

couldn't draw using paint and ink he could using ashes of

cigarettes," notes Jahanara. They

got married in October 1946. "It was Shafiqul Amin, the

elder brother of my sister's husband, who was the matchmaker.

We came to know that 'Zainul was a good man and what others

couldn't draw using paint and ink he could using ashes of

cigarettes," notes Jahanara.

Zainul started teaching even before graduation.

He started teaching at the college when he was in the fifth-year.

In the following year he got the Gold Medal in an all-India

Art Exhibition organised by the Academy of Fine Arts.

Before

this, he had to make an important decision in his life. He

was in the third year and it was time to choose his area of

specialisation. Mukul Dey, his mentor, wanted him to pursue

"Oriental Art", but Zainul thought it was important

for him to learn the Western academic technique than to restrict

himself in a stylistic ardour, namely oriental art that draws

on Moghul and Rajput paintings.

Zainul's intention was to capture the lives

and rhythm of the reality that he was a part of, and the best

way to capture that was to learn realism. Studying painting

served this cause.

Robust

talent and goodness came together to make up the character

that Zainul was. During her first sojourn to Kolkata Jahanara

Abedin had the opportunity to meet Jamini Roy, the famous

painter, who came up to her and announced, "From where

did he find this poter putul (iconic doll)"

and then added referring to Zainul, "Take care of this

precious gem, or else there will be a great loss

Before

the Second World War, Zainul was awarded the three-year British

Government scholarship in the UK, but the war prevented him

from taking it up. By then his temporary appointment as a

teacher was made permanent when the untimely death of Abul

Moin, the first Muslim teacher of the college, created a vacancy.

In

1943, the Bengal Famine put Zainul in the role of an artist

who had little energy to live in the aesthetised world of

beauty and grace. What he produced in a series of brush and

ink drawing was to become the most memorable images of human

suffering. In

1943, the Bengal Famine put Zainul in the role of an artist

who had little energy to live in the aesthetised world of

beauty and grace. What he produced in a series of brush and

ink drawing was to become the most memorable images of human

suffering.

"The Chinese ink that he used to use

made the brushes hard, and Zainul used to smash them with

a brick to soften them," Murtaja Baseer recalls his teacher's

foray into making do with whatever was available. Baseer believes

that the distinct "hard-brush-technique" resulted

from the manhandled brushes. "And he later deliberately

put that into use."

After marriage came the partition of India.

Zainul moved to Dhaka with his wife and became a teacher at

the Dhaka Teachers' Training School.

"Dhaka

had limited lodging facilities and we had to settle for my

mother's house at Johnson Road. This is how our life in Dhaka

began," remembers Jahanara Abedin. "He was constantly

disturbed, as his job did not suit him. And he had to do all

those works to make money -- from painting book covers to

the labels on oil containers," Jahanara explains.

Then he went off to Karachi where he was gainfully

employed as a designer in the government Publishing Department.

"The salary was more than six hundred rupees; but he

was not content, as his mind was set on establishing an art

college," Jahanara recalls.

In March 1949 he took up the position of the

principal of the art institute in Dhaka, one that started

off using a couple of rooms of the then National Medical School.

There was an outcry from the religious bigots, but Zainul

was undaunted. A resolute man, he soon started lobbying the

government for separate premises that would house the first

full-fledged art institute of the then East Pakistan. His

dream came to fruition in 1952, and a two-story house at Segun

Bagicha was alloted to the institute. Zainul could only turn

it into a college in 1963, the year the authorities agreed

to convert it into the Government College of Arts and Crafts,

which for the first time offered the Bachelor of Fine Arts

degree.

As a teacher Zainul was a dedicated soul.

Baseer, who entered the Government Institute of Arts in 1949

remembers how his teacher emphasised the practice of "drawing".

There were two ways he planned to strengthen the wrist of

a novice. One was to copy in a sketchbook the format of hand,

leg and face that Nandalal Bose put forward; and the other

was to do the same on a blackboard. It helped a lot for any

striving artist to gain control over lines and its rhythm,"

notes Baseer.

He

also remembers the day his revered teacher visited his home

to "have a look at the paintings." "The day

was March 22, 1955. I even kept his autograph signed on the

day," recalls Baseer. "He was as usual full of praise.

With a particular piece on a brown cardboard, I took caution,

I said, 'this is unfinished as I haven't covered a part with

paint,' but he was judicious in his verdict and he said, 'It

is finished and an excellent effort.' A good painter knows

when to stop putting on colours, he taught us that,"

Baseer testifies. He

also remembers the day his revered teacher visited his home

to "have a look at the paintings." "The day

was March 22, 1955. I even kept his autograph signed on the

day," recalls Baseer. "He was as usual full of praise.

With a particular piece on a brown cardboard, I took caution,

I said, 'this is unfinished as I haven't covered a part with

paint,' but he was judicious in his verdict and he said, 'It

is finished and an excellent effort.' A good painter knows

when to stop putting on colours, he taught us that,"

Baseer testifies.

He had the most cordial relationship imaginable

with his students. When Baseer was in the second year, he

and his friends, Qayyum Chowdhury, Rashid Chowdhury and others

even pulled a nasty prank on their beloved teacher. They forged

the letter of the governor's wife, inviting Zainul to meet

her on the evening of April 1. "We on that day wanted

to fool our most revered teacher. We kept a watch on him after

sending him the false invitation. When in the afternoon he

took a rickshaw to meet Lady Viqarunnessa, a friend and I

followed and stopped him to tell him about our design. He

was not angry. The kind of relationship we had with him can

never be imagined today," Baseer contends.

As an artist he related to Baseer what can

be termed an eternal motto for life. Zainul said, "You

build yourself to be a person so that when somebody praises

you, you will smile and if somebody criticises you, you will

smile."

In 1967 Zainul took an early retirement from

the post of the principal at the Government College of Arts

and Crafts. "I became aware of the disturbances at the

college, but he never used to talk about it. After he left

college, the Chief Secretary came with his wife to visit to

coax him to go back. But, his answer was clear, he said, "I

couldn't do much, as I was engaged in establishing the college.

Now, I like to devote my time to my own work," Jahanara

remembers. It was at that point of his life that he created

many of his oil paintings. He had always preferred to use

watercolour or brush and ink for their immediacy, but now

he had time to delve into oil.

"He went off to Karachi to sell his works,"

recalls Jahanara. He did a stint as Honourary Advisor to television,

film and publications department of Pakistan from 1968 to

1970. This was the time he spent mostly is Karachi.

As

a pioneer painter of this region, he devoted a lot of time

in organising the artists to advance the cause of culture.

Perhaps the sojourns to UK, Japan, USA and many other countries

in the mid-fifties made him more aware of the heritage of

Bengal. He organised the first exhibition of folk art and

craft at the institute's campus. He even urged fellow artists

to look for inspiration in the folk heritage of the time. As

a pioneer painter of this region, he devoted a lot of time

in organising the artists to advance the cause of culture.

Perhaps the sojourns to UK, Japan, USA and many other countries

in the mid-fifties made him more aware of the heritage of

Bengal. He organised the first exhibition of folk art and

craft at the institute's campus. He even urged fellow artists

to look for inspiration in the folk heritage of the time.

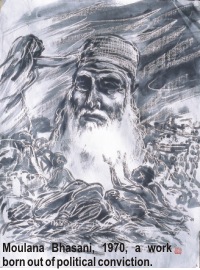

His political visions too were as clear as

the artistic ones. During the last few years of the Pakistan

regime, when the movements for an independent Bangladesh gained

momentum, Zainul aligned himself with the political force

that wanted freedom and fought for an identity of their own

based on Bangali nationhood. At a mass rally called by Maulana

Bhashani in February 1971, he publicly renounced the civic

honours he had received from the Pakistan government. On March

12 of the same year, he led a procession of the "Artists'

Revolutionary Council ("Charu O Karu Sangram Parishad)

and at a congregation at Bahadur Shah Park declared that the

Bangalis had no alternative but to fight for independence.

An organiser of the Dhaka Group in the 50s,

Zainul, after Bangladesh came into being in 1971, became immersed

in responsibilities of national importance. He suffered a

mild stroke in 1972 that resulted in partial facial paralysis,

for which he went abroad to seek treatment. Upon his return

he was entrusted with the responsibility of preparing a calligraphic

copy of the country's new constitution. He was also appointed

as chairman of the Bangla Academy for two years. He also was

selected visiting Professor at Dhaka University. In 1974 he

was nominated member of the governing council of the newly

formed Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy. He became one of the

first three national professors the following year. 1975 also

saw the inauguration of the two institutions he had long dreamt

of setting up -- the Sonargaon Folk Art Museum and the Zainul

Museum in Mymensingh.

The present show has created an opportunity

for the art lovers to discover the maestro by scrutinising

his real works. The Bengal Foundation wanted to turn the occasion

into a celebration of Zainul and his work.

At a seminar on December 24, where Abul Monsur

presented a paper and was attended by Ganesh Halui from India,

and Jalaluddin Ahmed from Pakistan. Ahmed wrote a book in

1958, the first major publication on Zainul.

The Foundation wants to instil in the young

generation the spirit that guided Zainul. "We arranged

for two buses sponsored by Grameen Phone to bring the school

children to the venues of the show. It started from December

14," reflects Subir Chowdhury who is not all too satisfied

to see the lack of attention this mega show has attracted.

"I have seen long queues in front of

museums abroad to see art shows. I feel there must be more

effort on our part to augment the interest of people on art,"

Chowdhury continues.

The novel attempt also has its detractor,

who accuses the organisers of displaying a forgery or two

in the retrospective show. Subir Chowdhury has a clear answer

to that, "There was a selection committee where eminent

artist like Kibria and Qayyum Chowdhury as well as Jahanara

Abedin were part of. They chose the entries. We honoured their

decision."

However, there are paintings that still remain

missing from the public domain. The oil works in Pakistan

had never been traced. And Jahanara Abedin gives more examples

of paintings that disappeared. "There was a visit to

Palestinian camps at Syria and Jordan in 1970. He worked on

60 to 70 paintings there. He was to have a show in Egypt but

by then the war broke out and the pictures were lost forever,"

laments Jahanara.

She also says that the paintings that are

kept in the Zainul Museum in Mymensingh are ill maintained.

"I asked my husband not to donate such beautiful and

important works to the museum when it was just being set up.

He was adamant he shared the sprit of Sheikh Mujib 'of building

everything from the root-level,'" exclaims Jahanara.

"Even the huge collection of the National

Museum is in need of a permanent space, as only a small portion

can currently be shown in their regular display," says

Jahanara. Her contention is clear: she wants the works of

the maestro who is the Shilpacharya (the Master of Arts) --

to be given the proper treatment by making sure that his original

works are preserved properly to inspire and delight future

generations.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|